The new director of the Staro Sajmište [Old Fairgrounds] Memorial Centre is a professor, scientist and ambassador, whose special interests include Hispanic studies and Judaism. Her father was a respected Yugoslav diplomat, which is how she came to live in Cairo, Chicago and Havana, and it was also thanks to him that she got to meet Che Guevara. Her husband, who died recently, was prominent writer and professor Aleksandar Saša Petrov. Her ancestry encompasses various professions, but they were patriots above all. The life motto of this diligent and competent woman is that it isn’t enough to only look to the future, because that future is unbearably easy and false if the past isn’t incorporated into it.

Her name is very rare and unusual, which is precisely what her mother wanted when choosing it for her daughter. The Krinon and the lily are the same flower, but Lily is a common girl’s name, unlike Krinka. In her later years, she learned that the word krinon comes from the Greek language. However, whenever she spent time in the western parts of the former Yugoslavia, she would be asked her if it is her real name, because they found it strange that someone could be given such an “ugly” name.

They didn’t associate it with the Serbian or Greek name of the flower, but with the word krinku meaning “cover” or mask, from which the verb raskrinkati [unmask/uncover] is derived. So, it is a rare name that was interpreted differently in the former Serbo-Croatian language depending on regional dialect.

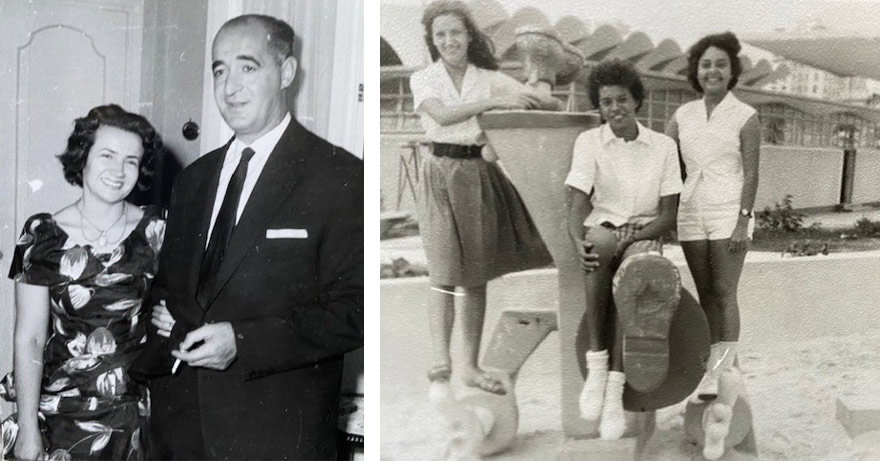

Krinka’s father hailed from Užice and her mother was from Kragujevac. They met as secondary school pupils, and the love that lit them up back then lasted for the rest of their lives. Krinka and her brother were born in the first years after World War II, into the baby boomer generation. They grew up in a happy family and during a time when hopes for a better future overcame the traumas of the recent war. Although she was born in Belgrade, in the apartment where the family continued to live later, the earliest memories of CorD’s interlocutor are linked to Chicago, where her father served as a diplomat:

“Those are not memories of a shining American metropolis, but of our family home and surroundings, nursery, my first school days, other kids from the neighbourhood. There were American children of various origins, which back then – at 4 or 5 years old – I didn’t even notice. One ritual that was repeated in nursery ended up ingrained in my memory, and it was thanks to that ritual that I learned to differentiate between the left and right sides of the body. Every morning, the children would stand and turn towards the American flag in the corner of the room, place their right hand on their heart and recite something, which wasn’t clear to me. But that’s how I learnt to distinguish left from right. At home we spoke only Serbian, and that revealed something important in my childish consciousness: that we are all the same in that we have our heart is on the left side, but that we are different in many other ways. Young children either don’t notice differences or overcome them easily. I didn’t comprehend clearly at the time the fact that Serbian and English are two different languages, and we children understood each other, probably more with body language than spoken language. But it was not easy for my brother, who’s three years my senior, because he immediately started first grade of elementary school. He had to learn English quickly, but also to defend himself from those who perceived him as some “other”.

Various parameters of otherness – gender, social, political, cultural – increasingly manifested themselves later during my adolescence and maturing, and later in life. I’ve learnt that ‘otherness’ has two faces: it’s a negative in the eyes of some, but in essence it can be a secret positive.”

Nevertheless, that feeling of being ‘the other’ also came to me later, and it accompanied me through life like a weird travel companion. Various parameters of otherness – gender, social, political, cultural – increasingly manifested themselves later during my adolescence and maturing, and later in life. I’ve learnt that ‘otherness’ has two faces: it’s a negative in the eyes of some, but in essence it can be a secret positive.”

She grew up in a loving and attentive environment, and her parents passed on different character traits to her during her upbringing. Her mother taught tenderness, creativity, sacrifice and beauty. She was a professor of French and Krinka followed in her footsteps as a student, discovering the charms of language, literature and culture. She was later led on that path by her husband, Aleksandar Petrov, who she says taught her to navigate literary waters and discover new landscapes not charted on maps:

“My father rarely said anything to me, which is why I remember the few simple pieces of advice he gave me, and which come from the treasure trove of traditional wisdom. First, that a person can gain a lot and lose even more – due to wars, natural disasters and various misfortunes, and we can never know if and when they’ll hit us. He believed that the most valuable thing is what I carry in myself and what I carry on me like a snail carries its home – health, intelligence, knowledge, love, spiritual strength – which I need to strive to preserve in all circumstances, not only good ones, but also those fraught temptations. Secondly, he told me that a person must be able to be soft like cotton, but also solid like steel, and that he must be able to adequately endure situations in which he might find himself, symbolically speaking, the situation of a “stableboy”, as well as a situation in which he may “reign supreme”. In other words, one should resist the temptations of powerlessness, but also of power. And thirdly, that roots are important, because one doesn’t live only in the present, but rather also as part of both the past and the future.”

Her value system was instilled in her early in her childhood through family stories told by her parents. She had two grandmothers, one in Užice and the other in Kragujevac. Her father’s mother, from Užice, came from the Tankosić family and was related to Voja Tankosić (1880-1915), a major in the Serbian army who died during the First World War. Krinka’s great-grandfather, Veljko Tankosić, was a priest, but in accordance with the time in which he lived, he was also something of a hajduk, something of a politician, and always a patriot. When the Austrians attacked Serbia by crossing the Drina, he and several of his friends killed some Austrian soldiers. After that became known, her great-grandfather fled to Montenegro. However, after Montenegro capitulated to the Austrians, he was arrested and deported to the Jindřichovice POW camp in the Czech Republic. He was already an old man by then, exhausted and ill, but the Austrians transported him back to Užice nonetheless, just to lead him tied up through the city and hang him publicly at Užice’s Dovarje cemetery. And they published a photograph in the newspaper:

“My grandmother, then a girl, had been present for that horrible deed. She later kept that photo on the wall of her room in Užice for the rest of her life, where we, her grandchildren, observed it, not understanding the horror it represented. But we later learnt a lot from the story of our great-grandfather Veljko Tankosić.

“I grew up in various social surroundings (in Chicago, Cairo, Havana), but those were always places limited by time and essential transience. Our family home represented that which was constant. We were returned ‘home’ to Belgrade and in Belgrade we were ‘living at home’.”

Krinka’s father, Boško Vidaković, was Yugoslav ambassador to Cuba from 1961-1964, and her memories from that country are a special story:

“Cuba was something fantastic and unforgettable. We arrived there soon after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. For the first few months, my brother and I studied Spanish at the only private school then operating in the country. All educational institutions – from primary to university – were closed because it was the “Year of Alphabetisation”, when all teachers and professors headed to the most remote villages to bring literacy to the people. The schools later started working again and I attended a high school that worked according to a new, Soviet programme.

Roots are important, because one doesn’t live only in the present, but rather also as part of both the past and the future

For the few foreign students, the school organised Spanish language classes every day after regular classes ended. Among us few were one American and several Russians, the children of experts sent by the Soviets as technical assistance to Cuba. Among my best friends, besides the Cubans who I recall fondly, was a Yugoslav girl (who soon returned to Belgrade with her parents and later became a famous painter) and a Dolores, whose father had fled Spain as a child after the Civil War, become an engineer in Moscow and married a Russian woman, and later moved to Havana with his family.

That was the second year after the revolution, then the time of the most dangerous crisis of the Cold War – the Cuban Missile Crisis. The majority of embassy staff members and their families were evacuated due to the nuclear threat, but my mother decided that we should all stay together, and what will be will be. My father played an important role for Yugoslavia during that crisis, but that’s another story. For this story, it’s interesting to note that he’d already met Guevara back in Cairo, when Che was visiting “friendly” countries for the (secret) procurement of arms. No one yet knew who Che Guevara was at that time, and during his visit to Egypt no one took much interest in him, except my father, who realised that he was a very interesting character who represented a new, revolutionary, but not yet quite clearly and publicly determined, government in Cuba. My father had very interesting conversations in Cairo with Che, and suggested that Yugoslavia be included among the ‘friendly’ countries of his tour. That’s how Che Guevara arrived in Belgrade, although that wasn’t originally planned. Thanks to all that, my father already had an established relationship with Guevara upon arrival in Havana, and he came to our house to talk with him. That’s also how I had the opportunity to meet him – from my high school girl’s perspective.

I remembered the Cuban crisis while I was serving in Israel, when the country was in a formal a state of war due to the invasion of Iraq (2003). Back then all the responsibility had been on my father, but now it was on me. It was certainly much, much more difficult for him, and knowing that helped me, together with my excellent team at the embassy, to overcome all the challenges we faced.”

Krinka’s pre-university education including school in Chicago (in English), then one year in Belgrade, then in Cairo at an American school, then again one year in Belgrade, then high school in Havana (in Spanish). That required a little more effort than it would have had she only attended schools in Belgrade, not only because of the different languages, but also because of different curricula:

“The most interesting was the high school in Havana, because I was learning in Spanish, but according to the Soviet school curriculum, albeit modified with ‘additions’ specific to the Cuban revolution. In Havana we also had one compulsory subject called the Plenum, which consisted of pupils discussing a wide range of topics – from whether there’s a God to the exporting of the revolution to Latin America.

Saša and I were happy people, we traversed lovers’ lanes together, followed creative visions together, discovered new worlds, shared a desire to discover something new, to take the harder but more gratifying routes

“I was a good pupil, but nothing exceptional. In primary school I’d been fascinated by astronomy. And although I found the natural sciences easier in high school, it was then that I became interested in philosophy and revolution (so I wouldn’t have to be in Cuba!) and that opened up a whole new world to me. But I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to study by the time I finished high school, other that I knew it wouldn’t be medicine or dentistry.”

She completed English language and literature and Spanish language studies in Belgrade, and earned her doctorate from the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb with an interesting dissertation entitled ‘Oral Tradition and the Written Word of Sephardim in Yugoslavia’. And what motivated her to opt for this topic?

“I enrolled in postgraduate studies at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade in 1969. The very next year, I took a job as an intern at the Institute of Literature and Art. My project manager at the Institute was an exceptional man: Dr Žarko Vidović. He always spoke about interesting things and told me, among other things, about his life in Sarajevo before the war, his imprisonment in Jasenovac and subsequent torment at a camp in Norway. But woven into these stories were his friends who were Spanish Jews (Sephardi) from pre-war Sarajevo and later Jasenovac. I found this topic fascinating, especially when my friend and colleague at the Institute, Dr Simha KabiljoŠutić, who is of Sephardic origin, told me even more about all of that. Their stories motivated me to register to do my doctoral dissertation on Sephardic culture. It seemed to me that it was a small diamond hidden in the dirt and that my mission would be to extract and study it. And That’s how it was. The diamond shone, but only after ten years of arduous work. Of course, I wanted to register the same topic at the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, but the then Spanish department had no time for me or my topic. The only alternative was to go to Zagreb and apply for a doctorate there. And so, I headed to Zagreb, for the first time in my life, not knowing anyone, to register this topic with Professor August Kovačec. The second time I went to Zagreb was to defend my doctoral thesis. When Sarajevo-based publisher Svjetlost published my book in 1986, it introduced the Jewish topic to our public in a big way. The book had three editions in Yugoslavia and one in Paris, in French. I’m particularly pleased that, twenty years later, this study inspired and encouraged a young generation of Hispanic studies colleagues to deal with Sephardim.”

Hispanic studies and Judaism are two important areas of Krinka’s scientific and translation work. The place of the Spanish and Jewish cultures in Serbia is a special topic that has no place in this story, just like the topic of why there is no department of Jewish studies in Belgrade. She says that this is an issue for the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade. She doesn’t know the answer, but she read recently read that a department for Jewish studies has opened at the faculty in Kragujevac.

Krinka was married to recently deceased writer and scientist Aleksandar Petrov for many years.

“Saša and I were happy people, we traversed lovers’ lanes together, followed creative visions together, discovered new worlds, but I must say that Saša taught me a lot when I started dealing with scientific work and literary translations. He was my best professor. We later supported each other in everything – life, work, creativity. We shared a desire to discover something new, to walk untrodden paths, to take the harder but more gratifying routes, which required more courage, strength, effort. And we didn’t regret that. Saša’s Dr Haos [Dr Chaos] book of stories and poetry book Erosova sveska [Eros’s Notebook] (which was released simultaneously in Belgrade in Serbian and in Moscow in Russian) have just been published. His new study on erotica in Serbian and world literature, will be published soon by Andrićgrad. For me, Saša was, and will remain, a reliable guiding star and my true spiritual home, as he wrote in one poem: “I choose a house according to the windows. / Branches to strike the glass at dawn, / shaft opening, / the scent of morning to wake me. And at night through the windows / for the stars to descend to my eyes / when I raise my eyes to the sky / and seek my mother among the stars”.

In Havana we also had one compulsory subject called the Plenum, which consisted of pupils discussing a wide range of topics – from whether there’s a God to the exporting of the revolution to Latin America

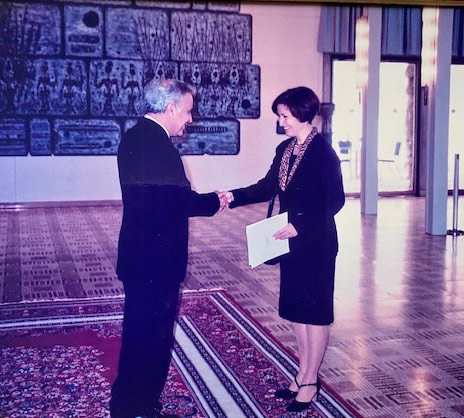

This diligent and capable woman was the ambassador of the then FR Yugoslavia, i.e., Serbia and Montenegro, to Israel from 2001 to 2006. And if she were to write her memoirs about that period, what would she write about as being the most difficult thing for a female diplomat in such a specific country as Israel?

“Israel isn’t a place where diplomatic service is easy or routine, but it is a challenging place that provides greater opportunities to express yourself professionally. I’d been to Israel before that, but exclusively for research purposes and international conferences. When I arrived as an ambassador, terrorism was in full swing. That is generally a country where things are never entirely peaceful, where it is occasionally very turbulent, where security is an issue raised to such a level of intensity that isn’t seen in many other countries. During the time of the invasion of Iraq it was in a state of war. That was the hardest thing professionally. In the middle of this situation, I was with a fellow ambassador having a very serious discussion about what to do, and my mobile phone rang as we were leaving the restaurant. The ambassador impatiently asked me if I’d received news about the invasion of Iraq, because he – like all of my colleagues – was obsessed with this issue. And I answered him with a smile and confirmation that I hadn’t, but that my friend asked me about a recipe. We laughed heartily.

That couldn’t happen to a male ambassador, who can only address one issue, while women are accustomed to working on multiple fronts at all times and viewing things from multiple perspectives. The most ordinary recipe reminds you of a reality that’s more complicated than politics. But Israel is much more than that. It is an extremely interesting country. Jerusalem is a place that’s home to the main holy sites of three world religions, but also a place of constant conflicts, a place where you walk through the past on cobblestone streets, and when you raise your gaze, you’ll see the future of new technologies. There human destinies move in the broad range of these complex coordinates. Although I’d been acquainted with Israel from before, that diplomatic experience – right there and right at that time – enriched me with new experiences. I returned from Israel to Belgrade much richer in spiritual terms, and I’d made a lot of friends there.

Krinka was appointment acting director of the Staro Sajmište Memorial Centre in Belgrade at the beginning of November. This appointed also serves to prove that the state is determined, after adopting the Law on this memorial centre, to finally also resolve its destiny. What is the significance of this memorial centre and its future?

“This appointment was a surprise for me, but primarily a great honour, as well as a great challenge. I consider it good that the hour has finally come to move from words to deeds and to start implementing this project, which is of key importance to the culture of remembrance in Serbia, as well as to the city of Belgrade, at the heart of which this centre is located. The first step was the adoption of the Law on the Staro sajmište Memorial Centre. The road ahead of me is a long one, filled with problems of various kinds, but every step we take will be a significant step forward. I intentionally say “we” because this is a project that cannot advance without cooperation among various interested participants, and above all the founder of this cultural institution, the Republic of Serbia. I believe this will be the case if we all clearly recognise the priorities of each stage of work and always keep in mind that joint action unfolds over the long run, and that we must be persistent and enduring. This project is extremely important because it will enable ours and subsequent generations of Serbs, Jews, Roma and all others to comprehend that the horrors that symbolically and historically represent the site of the “Old Fairground” were real and even more horrific than we can imagine today. it isn’t enough to only look to the future, because that future is unbearably easy and false if the past isn’t incorporated into it. Memorial centres on the sites of former concentration camps already exist in many other countries. And as far as we’re concerned, that isn’t just about repaying a debt to the victims, but making a fundamental contribution to our future.”