Dušan Otašević (83) explains simply and succinctly why he chose the motif of a grain of wheat and developed it in various techniques – from collage, via terracotta, to paintings in a combined technique of three-dimensional installations.

Dušan Otašević (83) explains simply and succinctly why he chose the motif of a grain of wheat and developed it in various techniques – from collage, via terracotta, to paintings in a combined technique of three-dimensional installations. “A grain of wheat carries within it both dying and the shifting of life cycles. A seed dies when it is sown, but from it emerges new life.”

The imagination and originality of this artist in his works is only equalled by his appeal as a precious interlocutor and reliable witness to events that have shaped the cultural map of Serbia. He was born in Belgrade just a few months prior to World War II reaching these lands, which condemned his parents to great struggles raising him. Fear of bombing compelled them to flee the city with the infant Dušan and find shelter in the surrounding villages, struggling to survive. Dušan’s mother was born, as Ana Krunoslava, in the Croatian city of Slavonski Brod.

“When she married my father, Milan, in 1938, the wedding took place in a church, as was the custom in the then Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and – as a Catholic – she’d had to convert. She also changed her first name and was married as Slavka. Never in my hood was a question posed as to who belonged to which religion or nationality. Right up until the 1990s, I didn’t know the national identities of some of my friends. And we all know what happened in the ‘90s and the results of all that counting of blood cells.”

Dušan was an only child for ten years, until the arrival of his brother. He had a harmonious, pleasant and happy childhood. His parents got on well until the end of their lives and the family functioned well. He remembers socialising meaningfully with his parents, playing a kind of game that brought them pleasure.

Never in my childhood was a question posed as to who belonged to which religion or nationality

“We liked to draw and we drew each other, drew animals… My mother drew beautifully, but father not so much. I remember the two of us laughing at his drawings. I saw the first reproductions in the magazine Graphic Review that my father used to bring home. For the possibilities of that time, they were extremely high-quality reproductions. Mother was a tailor for women’s lingerie childwho had a great sense for art. She stopped working after I was born, but she continued using her skills throughout her life. I remember how, in the miserable years after the war, she would turn over the collars and cuffs of mine and my father’s shirts. That was a special ability to turn over the frayed edges of the collar and cuffs, place them on the inside and you end up with a shirt looking like new that you can continue to wear. She had a ‘singer’ sewing machine that she did that on, and I later used that same machine for one of my works. She also had tailoring patterns, and many years later I found on one of them one of the sketches I’d done as a child, which I exhibited at an exhibition as my first work.

My father was also a craftsman, a typographer, which today is also a forgotten profession. His job was oriented towards the printing of books and our house was full of books. There are valuable examples from the library of the Serbian Literary Association that I still have today, because he brought home every book he worked on. That was a time when books were read and I grew up on books. If there hadn’t been books, I don’t know what I would have done as a boy and a young man during the summer holidays. I still use literature in my work to this day.”

In order to develop an understanding for Otašević’s work, it is necessary to know that he ventured into the waters of painting while he was still a student of the Academy of Fine Arts, during the years when the world scene was dominated by a movement with a somewhat forgotten name: pop-art.

“It was a new outlook with new expressive possibilities and I leaned into it somehow naturally. It was dear to me as a liberated form of expression, in contrast to what museum exhibits then represented. Pop-art was similar to what I’d loved as a child. They were wonderful works by typographers in numerous shops, particularly in Balkanska Street, advertisements for craft workshops, barbershops, hairdressers, when these advertisements were painted by anonymous… let’s call them artists. There were scenes linked to the profession and I always found that interesting. Just like the ‘cookbooks’ hanging in kitchens. When I started to paint, I tried, as far as I could, to connect that naïve expression with the realisation of a top artist. My artistic preoccupation was represented by that combination of something that wasn’t even acknowledged as an art form, but that nonetheless existed, and the recognised art of those years.”

Dušan’s father was tolerant in his relations with people, tolerant in his relationship towards faith, nation, everything different, and this artist’s entire life and all his actions show that he inherited that tolerance to a great extent.

“The understanding that he had is clear to me in my memory, particularly today, when everything is moving more towards closing up, towards some narrowing, which is calamitous for an artist, but also for the life of man as a whole. I said long ago that it is very important for a person to open the windows and doors of their studio, because something must enter from the outside. If you just close yourself off in your own world, that’s not good. It’s useful up to a level, but it doesn’t have a great future. My father had another good quality – he wasn’t bitter over injustices or adversity that would befall him. Let’s just say that prior to the war, he’d had a house that served for renting out. When the new government confiscated that house after the war, he took it relatively calmly and that never caused him to instil either hatred or rage in me, as a child.”

That breadth of perspective and sense of freedom formed the basis of Dušan’s upbringing in the home. After completing his sixth year of ‘gymnasium’ high school, he knew that he would deal with painting, and his father, who recalled the poor bohemian painters, thought that it would be a better idea for him to enrol in an academy of applied arts instead of an art school. He calculated that it would provide him with a more secure occupation. Dušan heeded his advice, but failed to pass the entrance exam. It was a year later that he applied for the Academy of Fine Arts, and did so with the great support of his mother, who was full of understanding for his choice, and was accepted.

Recall just how much of a percentage had been allocated for culture when Nada Popović Perišić was minister? If I’m not mistaken, it was four per cent of the total budget, while today it isn’t even one per cent

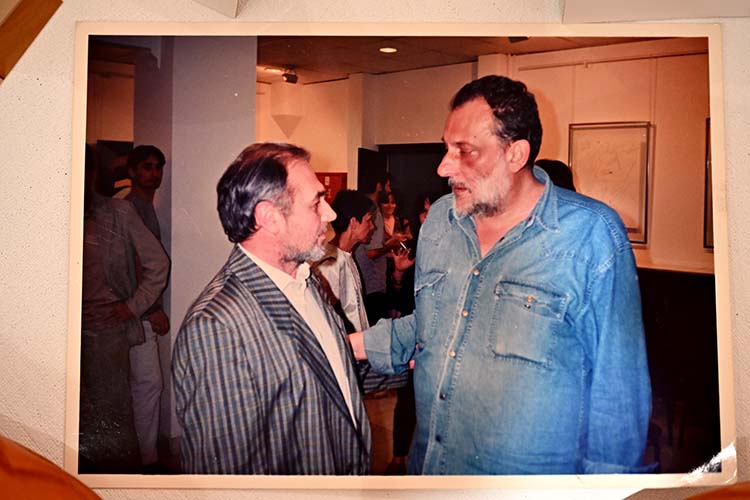

During his studies, and even subsequently, Dušan hung out with his colleagues, but mostly socialised with people from other professions, especially writers and directors. They shared a common language. He had his first solo exhibition while he was still a student, in 1965, at Atelje 212. He graduated a year later. It was also while he was a student that he met famous artist Leonid Šejka (1932-1970), one of the founders of the art group Mediala.

“We met in the reading room of the Academy of Fine Arts. He spoke about his views on art, about the idea behind Mediala, and he later also wrote the book A Treatise on Painting. That was very interesting and important to me at the time. It was also during my studies that I met the interesting Peđa Ristić, an architect who we called Peđa Jesus and who built a tree house on the Sava. I also had precious acquaintances with writer Boro Ćosić and his wife Lola Vlatković, film director Ljubomir ‘Muci’ Draškić and his wife Maja Čučković, painter Stojan Ćelić and his wife Ivana Simeunović Ćelić, and later we also socialised as families. I was delighted, but also slightly scared, when Muca offered me my first chance to work on set design for Bora Ćosić’s play My Family’s Role in the World Revolution, which he directed at Atelje 212. He was easy to develop an understanding with because he knew exactly what he wanted and what it was possible to implement on stage.”

Interestingly, it was back then, in early 1971, that Otašević first made a model representing the apartment that was the setting for Ćosić’s play. And that model served to shape the afscenography for the stage. Many years later, Muci’s daughter, Iva Draškić Vićanovič, today’s dean of the Faculty of Philology in Belgrade, testified that at some point that model had been found in the apartment of her parents, with her mother having played one of the nasty characters in that play. “It was my most favourite toy,” admitted Iva.

CorD’s interlocuter explains that friends were recognised according to the structure of their personality, in the way they understood one another without many words. He had friendships that lasted decades and only ended when that friend died.

“I have never been a member of any party. Throughout my life, I’ve tried to avoid succumbing to any ideology, because a person is limited by every ideology. By accepting one ideology, a person condemns those who ascribe to another, because they think it’s worse than their own ideology. I would say that was my lack of interest in the ruling ideology, but also among most of my friends. We were united by our artistic work, by the desire for each of us to achieve something in our work, or more precisely to show the best of our ability. I today recall pleasant socialising, content rich and meaningful.”

The current president of Serbia hasn’t visited SANU once. And that is a kind of sign and signal from that side. Restraint – I would say that it is mutual

The time of the single-party system of the former country is today often spoken of as a time of the “firm hand”, in which the League of Communists decided on everything and questioned everything. As aware as he was about the mistakes and bad moves of Tito’s government, Otašević insists that “uneducated and unprofessional people didn’t reach leadership positions”. And he cites an example:

“Even after Broz, during the time of Slobodan Milošević, more care was taken over culture than is the case today. Recall just how much of a percentage had been allocated for culture when Nada Popović Perišić was minister? If I’m not mistaken, it was four per cent of the total budget, while today it isn’t even one per cent. I have no doubt that this high percentage was also a result of the knowledge and skills of Minister Popović-Perišić herself, who was capable of fighting for a better position for culture, much more than the ministers that came after her. And it didn’t cross anyone’s mind to contest her for being part of the then ruling party.”

On the other hand, many artists didn’t fear showing a kind of deviation from the ruling ideology with their works during the time of the socialist Yugoslavia. And our interlocutor was among them.

“I had several works, one of which spent a long time in the exhibition of the Museum of Contemporary Art and it’s called Druže Tito ljubičice bela… [Comrade Tito white violet]. Of course, it clearly wasn’t in honour of Broz. But back then, in the second half of the 1960s, it wasn’t advisable to make fun of ruling attitudes and personalities. That work was large, 5×3 metres, and I created it for the first solo exhibition of the newly admitted members of ULUS [The Association of Fine Artists of Serbia], which was held at the Cvijeta Zuzorić Art Pavilion. They rejected me, the explanation being that the work was abnormally large, which is not collegial with regard to other exhibitors. I think that was an incomprehensible justification. Two or three years later, I exhibited that work at the university’s Kolarac Gallery. It all went without any consequences, but also without any reactions. I had other similar works with the figure of Lenin or ‘Mao Tse-Tung Swims in Communism’, and I was never called in for talks or reprimanded for those works. However, on the other hand, I never received a studio, unlike the majority of my colleagues, and I never went on a single study trip; and I didn’t get a job that I was more qualified for than the colleague who got it, but he had a party membership card and I didn’t.”

Dušan’s status was, and remains, that of a ‘free artist’, which implied great freedom and even greater financial insecurity. He created his own studio, in the attic of his father’s house, where he still resides to this day. He didn’t belong to any institution until 20 years ago, when he became a member of the most significant national institution: the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, SANU. He has been successfully serving as the administrator of the SANU Gallery for more than ten years. He is among those academics whose word is highly respected, although he rarely advertises that fact. Tactical and restrained, he supported the positive changes initiated by Vladimir Kostić in his capacity as SANU president until recently, but he has a hard time understanding the fact that nearly four decades after the Memorandum marked the work of this house, its shadow still looms over SANU.

“Meetings and discussions on this topic were organised at the Academy, and I’d thought that it was a topic that had long since been dealt with. For some reason, that topic is still rolled out today. I never understood the actual aim of those manipulations and always appeal for the need to be restrained, not to allow the use of the Memorandum for the purposes of everyday politics. The Academy is an institution that’s comprised of individuals who have their own views. Simultaneously, the Academy is an institution in which new members are chosen according to clearly established rules, and here it isn’t possible for some godfather to get you into SANU – at least I know of no such case. But I do know that the ceremonial sessions commemorating SANU Day, which numerous guests and the state leadership, headed by the President of Serbia, are invited to attend, have only been attended by presidents Boris Tadić and Tomislav Nikolić since I’ve been at SANU. The current president of Serbia hasn’t been once. And that is a kind of sign and signal from that side. Restraint – I would say that it is mutual.

Even after Broz, during the time of Slobodan Milošević, more care was taken over culture than is the case today

“The Academy is a conservative institution in accordance with its organisational structure, but in recent years it has been taking steps towards opening up. I don’t think it should be avant-garde, but it must have an appreciation for reality. If film has existed as an art form for 100 years, isn’t it time to open up the possibility for a top film director to become a SANU academic?”

Dušan Otašević spent almost half a century married to Mira Otašević, who departed in 2019. An exceptionally interesting and talented individual, she graduated in literature and dramaturgy and worked as an editor at Television Belgrade. With her novel Gorgone [The Gorgons], Mira Otašević, who went by the nickname of Miruška, was shortlisted for the 2017 NIN Award. Together they have a son, Uroš, and a grandson.

“We didn’t succeed in celebrating our 50th wedding anniversary because Mira passed away that year. She left suddenly; there was no illness to prepare me for it. We had a good life together, and it’s very fortunate to live with someone all your life and to have understanding for one another and to be able to discuss what you do for a living. I created the exhibition that’s currently running at the Zepter Gallery in loving memory of Mira. I promised her during her lifetime that I would make it, but I never got around to it. When Mira went to that better place, as they say, I prescribed working therapy for myself and I think she would be happy with what I did.”