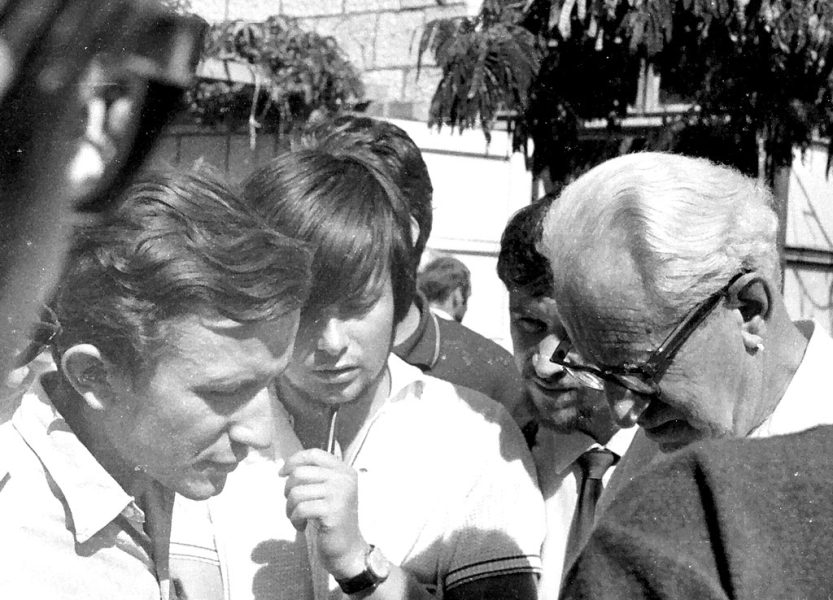

He is among the greatest wizards of the written word, having authored plays and novels that have made him a Croatian classic. His works have been translated into fifteen languages and his most famous play, Croatian Faust, has been performed in Belgrade, around Europe and in the cities of the former Yugoslavia, but never in Zagreb. An English studies expert and philosopher by education, and a leftist by conviction, he was forced to leave Croatia during the rule of Franjo Tuđman and lived as a highly respected emigrant in Germany. He today resides on a Croatian island and only goes to Zagreb and elsewhere in Europe when required

Slobodan Šnajder (born 1948) has been in the spotlight once again in recent months, with his latest novel, Anđeo nestajanja [The Angel of Disappearence] having attracted a lot of attention. He spent a full eight years working on it and it was published by Croatian publishing house Fraktura, while Novi Sad’s Akademska knjika is responsible for the Serbian language edition, just as it published his previous novel Doba mjedi [The Brass Age], which had four editions in Croatia. Translated into fifteen languages, critics described it in the newspapers of Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere as an epic novel that can undoubtedly be considered a masterpiece of European literature. The first reviews of The Angel of Disappearence also suggest that Šnajder has “once again tailored a wonderful novel and obviously shown and proven that his literary prowess doesn’t know or acknowledge any boundaries” (Jaroslav Pecnik).

During his many decades of writing, this distinguished intellectual was also a columnist for Rijeka’s Novi list newspaper, right up until the point at which the people in power no longer wanted to endure his stinging remarks. He hasn’t generally been in love with any government. He spent just a short time – while social democrat Ivica Račan was prime minister – a director of the renowned Zagreb Youth Theater, but he had to leave due to the repertoire policy for which he advocated. He is praised across Europe as a top-class playwright, while his plays aren’t generally staged in Croatia, with a few rare exceptions. He doesn’t complain about that, and as a rule he swiftly, and often cynically, interprets and explains individual moves of the government, after which everything is clear to all.

Šnajder is the biological offspring of father Đura Šnajder, a poet and writer, and mother Zdenka, who in 1942, as a member of the Yugoslav National Liberation Movement, and having barely turned 18, suffered atrocities at the Ustasha concentration camp in Nova Gradiška. Šnajder has also previously described himself as the “wild son” of Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža (1893-1981), as he explains in this CorD Magazine interview.

“An illegitimate son is that unpleasant surprise that turns up when a father dies, particularly if he is famous and rich, and such a son announces his inheritance aspirations. There is, however, no such scramble over Krleža’s inheritance. One anecdote suggests that one of the most persistent and vocal on the matter of inheritance after Krleža’s death was his chauffeur.

“The wild son in this case would be one that the father wouldn’t acknowledge, as is often the case. But when Krleža could do no more about this issue, the chauffeurs turned up, of course.

“Specifically, we today live in a country, in its literature, as if Miroslav Krleža had never written a single word.

“In truth, and as you’re alluding to, I once stated that I’d be happy to be just such a ‘wild son’. That calculation turned out to be mistaken: there’s nothing to inherit there. We have to do it all ourselves. Time and again. With great respect to the bard, but time and again. Well aware that we won’t leave anything behind either. I also have wild grandchildren, in addition to three real ones.”

His parents divorced early on and he grew up alongside his mother.

If the criterion of a state’s worthiness is the happiness of its citizens, then there was still more of that happiness in Yugoslavia than there is today

“My mother and father fought difficult legal battles over their children, my sister and me, which is strongly reminiscent of some contemporary battles, for example with regard to Severina. My mother took the victory in that tough litigation, that is to say that she took the children. But my father then disappeared almost entirely. You can read about that in the concluding chapters of the novel The Brass Age. I inherited the traces of their battle in correspondences, when they were ripping each other’s guts out, and I’d rather I hadn’t.”

And yet, despite everything, he had a happy childhood.

“I went to primary school with rural kids because we lived on the outskirts of the city, in a settlement that wasn’t yet a city, but was ceasing to be a village. I was raised in a female family, with my mother and grandmother, an extremely intelligent matriarch to whom life really hadn’t been kind. Her son, my uncle, had never returned from Mauthausen concentration camp, where he’d been sent after Jasenovac.

He was literally killed on the last day of the war, in May 1945. A candle always burned for him in front of the Partisan memorial (in fact a piece of paper). My grandmother received compensation for her son, worth about 30 euros by today’s standards.”

When I ask him what he inherited from his parents and how his upbringing looked, he responds as follows.

“Genetics, which we of course don’t choose. In this sense, I received a Greek gift from my father: I have a gene that always concerns cardiologists. In black and white terms, it tells me that I have an elevated risk of heart failure. My father died of a myocardial infarction when he was precisely the age I am now.

“So, he disappeared from my childhood, only to reappear in my life sometime during my high school days. I must state immediately that I attended a gymnasium high school that was incomparably better than what is referred to by the same name today. The teaching faculty was incredible and I still have fond memories of many of my teachers. The teacher of Croatian instilled in me respect and love for Crnjanski, and subsequently also for Krleža. I really enjoyed reading my early works to the class. I was always vain and needed an audience.

“Surprisingly, when it came to what should have been the male component in my upbringing, I settled for myself. I really liked football. I went to matches, and naturally cheered for Dinamo. Entering the stadium was a problem, of course. It was necessary to find any adult fan to get me in for free. And that’s how I was adopted by many; I was a wild son of many. Krleža didn’t attend football matches.”

What remains today of that leftist who came to Belgrade to support the students back in 1968, as a delegate of the University of Zagreb?

“I will first tell you something about that ’68; that generation that strove with all its might to be born politically and culturally. A man usually grows up by resisting authority. The Yugoslavia of that time was led by a man with huge political instinct – even Đilas admitted that to Tito – and great credit for the success of the only authentic revolution on our territory. The Ustasha fascists also called their movement a revolution, and they christened it as openly totalitarian, because for them that term didn’t have the horrid connotations that it does today, on the contrary. But the totalitarian revolution is a revolution against the very concept. Like calling Tuđman’s conservative.

“So, on the one hand, we had as leader a man who was indisputably worthy of credit for the relatively peaceful childhood and youth we’d had up until then. But we saw that the matter of his revolution had stalled, that the revolution – as Krleža said (but certainly not to Tito, particularly not face to face) – was maneuvering like a locomotive at a secondary shunting station. The regime appeared old to us, incapable of the changes that were on everyone’s lips declaratively, while in reality nothing changed.

We today live in a country, in its literature, as if Miroslav Krleža had never written a single word

At that juncture, the revolution pusswas scared of its own youth. Don’t forget that Edvard Kardelj, despite being one of the most intelligent in Tito’s close circle, pleaded with the Central Committee to deploy tanks against the Belgrade students.

We then took to the streets, and it could easily have been a bloodbath in our country like the one in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

Today, after the collapse of his project, I think better of Tito than I did back then. But the objections to him that are raised by my Anđa Berilo in the novel The Angel of Disappearence, as a person devoted to the cause of his revolution, are in essence the objections that my generation raised against Tito’s regime in 1968.

“The 1968 rebellion coincided precisely with events at European universities, especially French and German ones. We had links with them, and many of us were long under suspicion by the ‘Services’ due to those links. The files on us were simply passed from one hand to another in the 1990s. The Services have since pursued different and even opposite ends, protecting countries hostile to one another, but they are basically the same people. That’s what it was like with the Gestapo in France. The West didn’t only need people who knew how to draw and fire rockets, rather first and foremost it needed policemen. All told, this is an as yet unwritten chapter. I also owe something to my generation.

“The way things stand today, the recent Croatian history begins in 1971. In your country, that would mean from Tito’s showdown with Serbian liberals. However, the recent Croatian history begins in 1968.

Still, as I say, I think better of Tito today than I did back then. This is explained in particular by my studying of Tito’s resistance to Stalin. If there had been no such resistance, we would have spent our youth in the grey environment of the countries of the so-called people’s democracy, i.e., in the lands of the Soviet labour camp.”

Is it today possible to be a publicly declared leftist in Croatia or anywhere on the territory of the former Yugoslavia without being professionally sanctioned? How acceptable, unpleasant or dangerous is that today?

“I’ve never thought about it in that way. Even when I received threats that included descriptions of my physical elimination that would be executed with such expertise that I’d be able to experience it to the full for an hour, I didn’t immediately rush to the police. And I said that there are highly rated experts. However, I don’t know what a declared leftist would be? It looks like an apricot compote on which it is stated what’s in the jar. I NEVER decided to be declared as an apricot compote. I never thought about the risk. I thought for myself, only being sure not to be adopted by someone crooked.”

Can you make a living from writing?

“I’m a Croatian pensioner, and that category is more or less social. My foreign publishers don’t like that, so they occasionally send me some money. I certainly have more than most of those who do what I do. If they really aren’t academics.”

How much are you impacted by daily politics today?

“Napoleon’s famous remark on the subject crosses my mind: everyone talks about destiny. Politics is today destiny. So much for Bonaparte. By the way, he was the first to create a secret service, a very effective one. And previously in this interview I said that destiny is genetics. All I can say is that, in getting old, I’ve developed a disdain for such a political class. It seems that this class in our lands, in the former Yugoslavia, is outgrowing its framework by some necessity into what Đilas calls a new class, i.e., a nomenclature. What is actually something of a novelty in this sense, and has been happening recently in Croatia, is that the political class has been directly transferring public money in dizzying amounts to their companies, under their own ownership. For example, one minister transferred millions of euros to his own company. Nothing is hidden anymore, even though it’s nefarious. This has somehow unfolded in a roundabout way so far, though the result is the same. Now they no longer pussyfoot around. The political class promotes itself into the high bourgeoisie. So far without any risk!”

Is there any positive heritage from the former country left to us?

“It exists in such a way that it no longer exists. There are memories. If the criterion of a state’s worthiness is the happiness of its citizens, then there was still more of that happiness in Yugoslavia than there is today. But let’s admittedly be under no illusions. Yugoslavia was far from an ideal country, but if we look back on it today, what I said seems true to most of those who were born in these lands.”

What is the greatest success of the Croatian authorities since the creation of the independent state?

“Well, that would imply that many successes exist, and then one that is the biggest. Dajte-najte [Don’t leas us on], as we Kajkavian people say. My masochism also has limits.”

Šnajder’s theatre drama Croatian Faust has to this day remained a “dark object of desire of the Croatian petty bourgeoisie”, never performed at the Croatian National Theatre. If it had ever been performed there – as it was in 1982 at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, becoming that theatre’s most popular play for the subsequent ten years – would anything have changed regarding the perception of this play and its rating when it comes to contemporary Croatian drama?

“I’m reluctant to talk about it because I’m already sick of that topic. I keep raising two fingers, and as if to pray, Lord, I’m here, the wild son of this one or that one, give me, for God’s sake, take notice! But I basically don’t care about that. There is a chapter in the novel The Angel of Disappearence entitled ‘Le Danse macabre croate’, i.e., ‘The Croatian Dance of Death’, in which I stated something conclusive about that unhappy topic, with the wish that I never have to speak publicly about it again.

All I can say is that, in getting old, I’ve developed a disdain for the political class as it is

“And here you are asking. It boils down to something that survived the disintegration of the country as a taboo and continued to endure in another that was created according to the opposite ‘user manual’. So, how come? There is something curious in all of this, something scurrilously- comical. It scurrilously points to grinning skulls.

“Well, may they all rest in peace!”

Snježana Banović had wanted to stage Croatian Faust at the Croatian National Theatre when she was that theatre’s director of drama, but?

“Mladen Tarbuk, the intendant of the Croatian National Theatre in the period when Snježana Banović was its director of Drama – forming, by the way, by far the most informed duo to date – indeed mentioned in one interview that he intended to stage that play. But a repertoire proposal was never formed. The two of them certainly thought about it, especially Snježana Banović, but she was very quickly fired from the position of drama director, and that was precisely because of a guest appearance in Belgrade that she had planned. And then, unfortunately, Mladen Tarbuk was also hung out to dry. Banović developed great distress, not only for that play, but also for thirteen others that had never been performed, in many places, including in her book about the crazy ‘80s, which you have in Serbia in the very good edition of Geopoetika.”

Your new novel, The Angel of Disappearence, is a kind of ode to a Zagreb that no longer exists. What is Zagreb today for Slobodan Šnajder?

“Well, just as you exposed who my biological father was, and to whom I offered myself for adoption, Zagreb is forever my birthplace, is it not? Only Homer was born in as many as seven Greek cities. The Angel of Disappearence is dedicated to Zagreb; it is a novel about the city, just like Döblin’s Alexandarplatz is a novel about Berlin, if a small one can be compared to a large one. I live on a small island in central Dalmatia. My sources are there, and one shelf is already full of my books. Terrible.”

What does this writer read; does he have his own favourite writers?

“I’m a reading machine. One anecdote states that my father, old Kempf from The Brass Age, read the entire literary production of Croatia in his time as a critic. I don’t deal with critiques, but I’m interested in what my colleagues write.

“I’ve been reading a lot of Kiš recently. My great literary role model is Roger Martin du Gard, a forgotten French Nobel laureate, and his Thibault family. That’s how I would like to write. I don’t think I’ll succeed.”