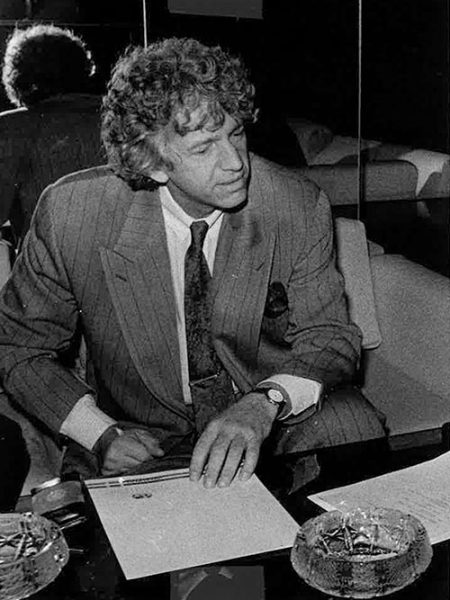

He held the title of the most successful Belgrade architect in Paris for decades. He has designed hundreds of buildings that are located on four continents and belong to the likes of the Sheraton, Hilton and Louis Vuitton, and also include congress centres, presidential palaces etc. He has been living in Paris for much longer than he resided in his native Belgrade, but Čubura remains his hometown. He was raised in the spirit of inter-ethnic tolerance that characterised the Yugoslavia that no longer exists

Dubljanska Street is located in the Belgrade neighbourhood known as Čubura. The street is named after the small Mačva village of Dublja, which is known as the site of the 1815 battle of the Second Serbian Uprising that saw the Serbs defeat the Turks. This street is also known for its inclusion in the title of Miodrag Zupanc’s play White Rose for Dubljanska Street. And it was in this very street, on the eve of the outbreak of World War II, that CorD’s interlocutor, architect Toma Garevski, was born.

His father Dragan, a Macedonian, was a representative of Macedonian companies in Belgrade. His Jewish Mother Ružica Liper survived World War II thanks to being married to an Orthodox Christian. And her sister Dragica also managed to save her life by marrying a Slovenian man.

“With the experience of the horrors of war and mixed marriages, they raised me to love Yugoslavia, primarily because of the inter-ethnic tolerance that really existed back then.”

Toma completed his basic schooling at all the schools of the Neimar and Pašina Brdo neighbourhoods, but he also attended Knez Mihailova Street’s Dr Vojislav Vučković Music School, accordion department.

“I remember my childhood for the fact that family order was respected in the house, while the street was where we children played freely. I thus fell in love with Čubura. We planted trees in the park on Neimar that are still there today. We lived for football and played with a rag ball. A relative from America came once and before departing asked us what we would like him to send us when he returned to the States. Without thinking, me and my younger brother Boris told him to send us a football. We spent the next two months dreaming of the ball arriving from America. And when the package finally arrived, the family and all the children from the street gathered. Opening that package was the greatest ceremony that I can recall. And the greatest sadness. Instead of a standard football, the relative had sent a ball for American football. We didn’t even know what that sport was, nor could we play football with that ball. There wasn’t a friend who didn’t cry.”

Čubura is a holy place for all lovers, but Toma went further: he claims that Čubura is also a way of thinking, a code according to which a thug must be an educated person, sufficiently courageous and ready to succeed in life. I know that this opinion was shared by his fellow Čubura native and immortal actor Dragan ‘Gaga’ Nikolić, but also by the Zupanc brothers, director Dragomir and the aforementioned Miodrag, who were born and continue to live in Čubura.

Čubura is a way of thinking, a code according to which a thug must be an educated person, sufficiently courageous and ready to succeed in life

After completing his architecture studies in Belgrade, Garevski headed to Paris.

“I also completed my military service and went to Paris to buy a synthesizer. I already played the accordion in the Mile Lojpur Orchestra and needed to have a synthesizer for the summer stages on the coast. After three months working in the office of great French architect Jean Balladur, I bought a synthesizer, but the work took off and was too enticing for me to leave. That’s how I ended up staying.

“You should keep in mind that in high school I was the worst student of the French language. Throughout the entire period of my schooling, I ‘earned’ by drawing and playing the accordion. Instead of knowledge, those were the aces up my sleeve, and it was because of those skills that the teachers turned a blind eye to everything that I didn’t know. When I came to Belgrade to attend the celebration marking the 20th anniversary of graduating high school, my French teacher, Professor Nikačević, was still alive. I told him that I lived and worked in Paris, and he was so taken aback that he almost had a stroke.”

Toma spent five years working in the atelier of Jean Balladur and was a member of the team that worked on the project for a hotel in Vichy. He was told in confidence that his work was the best, but he wasn’t rewarded for his efforts because the name behind the project was more important than anything else to the president of the municipality in Vichy.

“It was then that I realised that it would be more profitable for me to work abroad as a French architect, as opposed to being a foreigner in France. I firstly had to graduate in architecture studies in Paris, because they only acknowledged two years of my studies at the Belgrade faculty. I thus formally became a French architect, though that didn’t help me a lot – because you can’t succeed in Paris if you don’t have family ties or influential connections. And heading out into the world meant that I initially worked in Lebanon and the Middle East.

“Those first experiences of mine were also interesting. I’d learnt in Belgrade that it was a great success if you create the best possible project in a small space, say by packing a three-room apartment into an area of 70 square metres. In contrast, in Beirut, I had orders to design a three- or four-room apartment on an area of 300-400 square metres. That’s called a clash of worlds in architecture.”

Very strict architectural rules exist for all large buildings… For me it has always been important for my projects to fit into the ambience and philosophy of the surrounding area

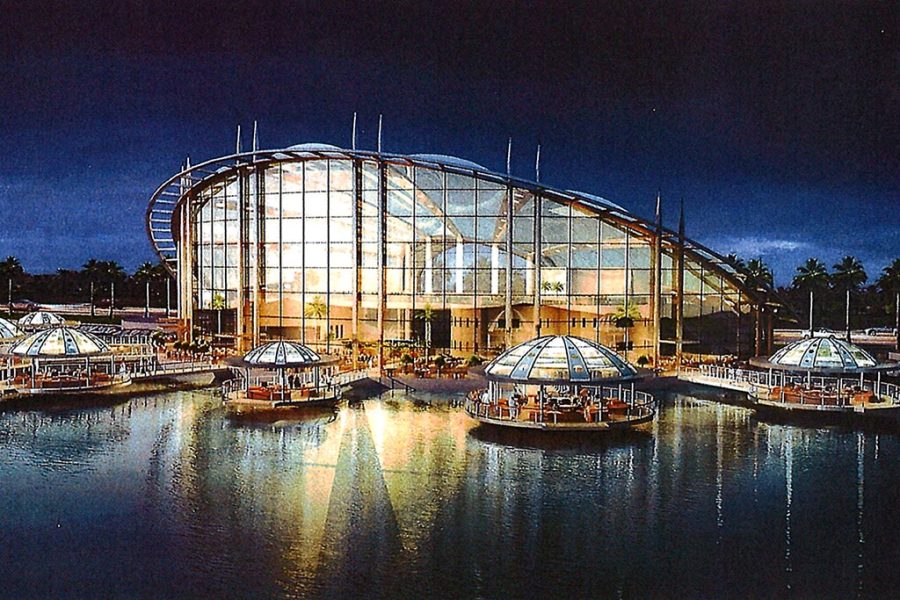

This architect worked wonders in Saudi Arabia. And he was assisted in doing so by a certain Rafic Hariri, a key man for capital projects in that country who happened to like Toma’s works and ideas. That’s how he ended up building a residence and hotel that had been commissioned by Saudi King Khalid and had to be completed in eight months. And to be the most luxurious edifice the world had ever seen.

“From foundation to roof, the Intercontinental Hotel was built in eight months, in the desert, in the middle of nowhere. When I returned there 10 years later, I couldn’t even find the hotel. A large city had been built around it. After King Khalid, his successor, King Fahd, also wanted to work with ‘the fastest architect in the world’. We built a Sheraton hotel and many other projects near Mecca: palaces, hotels, residences etc. Invitations followed from other countries. I implemented the Presidential Palace in Djibouti and have remained friends with the President of Djibouti to this day, having worked there for about fifteen years. All these projects opened doors for me in Paris and on the French Riviera. And the Automobile Museum in Paris was among the first.”

He describes himself as being like a general practitioner, because architects constantly ask him to do this or that, convinced that he can design a hospital, hotel or luxury palace, as well as an ordinary residential building. Once in Skopje, after an earthquake, he participated in a design contest for a cemetery! In stark contrast, he had the great pleasure of receiving the opportunity to contribute to the luxury monograph ‘Ces belles mairies de France’ [The Beautiful Town Halls of France], detailing the most beautiful municipal buildings where people most like to get married in France.

When fashion house Louis Vuitton decided to construct its business palace in Paris’s Avenue Montaigne, at the very entrance to Champs-Élysées Square, the job was given to Toma. He offers an interesting explanation regarding this extremely prestigious endeavour.

“Very strict architectural rules exist for all large buildings. Apart from that, for me it has always been important for the projects that I do to fit into the ambience and philosophy of the surrounding area. If I design Hilton and Sheraton hotels in Saudi Arabia, I utilise their history and the local architecture. I draw inspiration from their legacy. The territory on which I built the Louis Vuitton palace, otherwise situated in the most exclusive part of Paris, generated enormous interest. And it was terribly expensive, costing around 35 million francs at the time. Then Vuitton came and bought it for 70 million! Why the company had done so wasn’t clear to anyone, but an answer came quickly: it was important for Vuitton to have an address on the Avenue Montaigne, because of the prestige the company had in Japan and around the world. As such, the Palace had to have a highly representative look. The investor was Boussac, and we built a penthouse apartment for Mr Marcel Boussac and everyone was very satisfied.”

I quickly realised that it would be more profitable for me to work abroad as a French architect, rather than being a foreigner in France

Famous Serbian architect and university professor Mihajlo Mitrović (1922- 2018) reviewed this building in his capacity as a critic in 1990.

“This latest work of architect Garevski, in the heart of Paris, largely compensates for missed opportunities and represents his architecture in the best way, showing the success of gradually replacing old buildings with new edifices, larger spaces and new functionality. Installed on the new, modern building is the complete Florentine portal that previously adorned the demolished building, shaped with marble squares in an aluminium grid. With this approach, Garevski has brought back to Parisian architecture, and affirmed in a new way, the controversial idea of Violletle- Duc that a deliberate and purposeful reconstruction in architecture should mean establishing a finished structure that never previously existed. And indeed, the new Vuitton store today shimmers with rich new spaces and exclusive interiors, while at the same time supporting, tranquilly and in a refined way, and enriching, in a modern way, the atmosphere of the boulevards of the Champs-Elysée, the world’s most beautiful boulevards.”

After Toma, his younger brother and fellow architect, Boris, also came to Paris, and the two of them have for decades had a joint company, AXE, based in Paris and on the French Riviera in Antibes. Toma has long been married to Anđelka, his high school sweetheart who hails originally from Kruševac and graduated in technology studies. One event in which the main actors were Toma Garevski and his wife remains as a historical anecdote and film script story. Namely, he granted himself the right to bring his wife to the reception commemorating the opening of that hotel and residence in Saudi Arabia, which he had completed just a few days ahead of that famous eight-month deadline. The king had invited several thousand guests to the reception, but the only woman in attendance was Anđelka Đeka Garevski. That was because only men had been invited, and Toma didn’t want to attend the reception without his wife. In a country where, at the time, women were deprived of even the most basic rights, where they were not allowed to even touch the steering wheel of a car, let alone attend a reception with men, Toma was a hero who’d completed a magnificent building in the middle of nowhere ahead of the deadline, so for him everything was permitted.

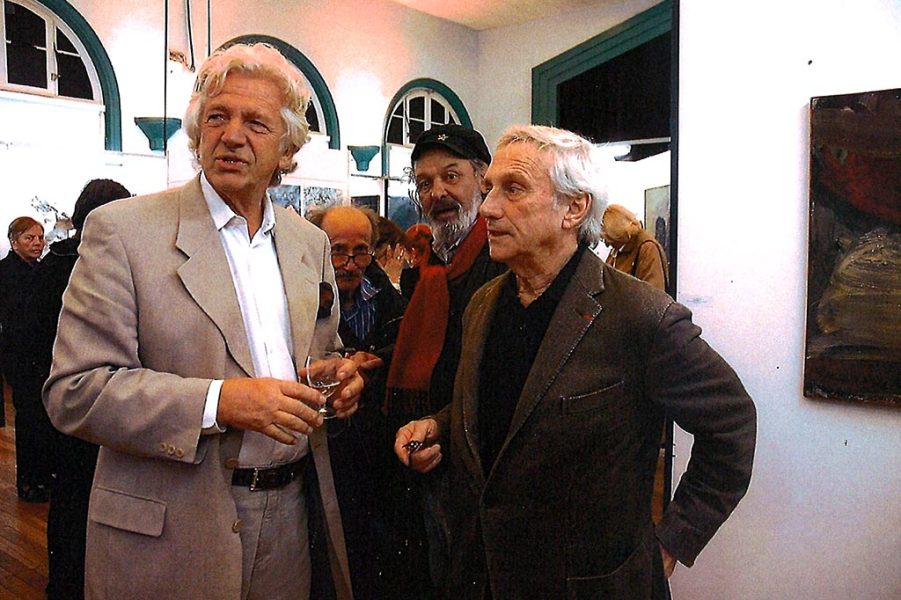

Toma and Anđelka are the proud parents of two successful daughters. Gorana is communications director for Channel 1 of French television company TF1. Sabina is the director of a real estate company. Gorana has a daughter, Gaia, who just turned 17 and attended her birthday celebration with a boyfriend for the first time. Apart from his family and work, Toma has also spent time with friends from Belgrade and Yugoslavia who’ve come to Paris, stayed, left, and returned once again. He became friends with famous ballet dancer Milorad Mišković and would visit him at his place in Nice, together with Politika newspaper’s Paris correspondent Aleksandar ‘Saša’ Prlja. Toma’s office has a gallery section that includes pictures by his painter friends – from Vladimir Veličković, Ljubomir Popović and Petar Omčikus, to Milorad ‘Bata’ Mihajlović and Miloš Šobajić – and sculptures by Nikola ‘Kolja’ Milunović.

“My first friend among painters was Đoka Ivačković, who was actually an architect by education, just like Veličković. That’s also how I very quickly made friendships with our other painters. We often socialised at my office. Ljuba Popović lived around 200 metres away and always came on foot. Veličković made it a practice of parking his car and visiting my office on the way to his studio. Bata Mihailović was my fellow Čubura native and I had a special way of communicating with him. Kosa and Petar Omčikus really liked us to visit them. I remained friends with Miloš Šobajić until his last day. We were all inseparable at celebrations, at the Cultural Centre, at the exhibitions of all of them. We did everything we could for each other, without a moment’s thought or interest. A proper gallery of their works, which I received as friends’ gifts, has remained in my office as a reminder of that time. It could thus be said that we still hang out today.

Vlada, Ljuba, Kosa and Petar, Bata, Miloš… We were all inseparable at celebrations, at the Cultural Centre, at the exhibitions of all of them

“We rejoiced in every arrival in Paris of our friends from Belgrade. And that was particularly so during the years when Dragan Nikolić was performing here. And he, like me, initially spoke French disastrously, but learned extremely quickly and forged a successful career in Paris. His wife Milena also came often and those were unforgettable gatherings.”

Toma also spent his summers with his friends from Belgrade. He spent his summer holidays in Cavtat [a town on Croatia’s Adriatic coast], but used his boat to visit his Parisian and Serbian friends holidaying everywhere from Istria, via the islands, to Dubrovnik.

“We often went to Dubrovnik to see our [Yugoslav] artist Jagoda Buić, while it was obligator for us to go to Ljuba’s place on Korčula. I would drink coffee every morning with Zoran Radmilović, who had a house in Cavtat. Many dear people were there, including Ružica Sokić, the married couple Milka Stojanović and Živan Saramandić, famous cardiologist Ninoslav Radovanović. Us friends from Belgrade who had addresses all over the world would have a nice time socialising once a year in Cavtat and on the Adriatic.”

This architect was always ready to help when he was asked to do so in Paris by “someone among ours”, which is how he still refers to all people from the territory of the former Yugoslavia.

“I’m always ready to help the Embassy, the Church and the Cultural Centre. We renovated the entire Serbian church in Paris, but also the Cultural Centre of Serbia; at the Serbian ambassadorial residence we arranged the balcony and roof, installed gas etc. There is still a lot of work to be done at the ambassadorial residence, which is one of the most beautiful buildings in Paris and is unbelievably well positioned opposite the Eiffel Tower. I hope to continue what I’ve started with the new ambassador, Ana Hrustanović.”

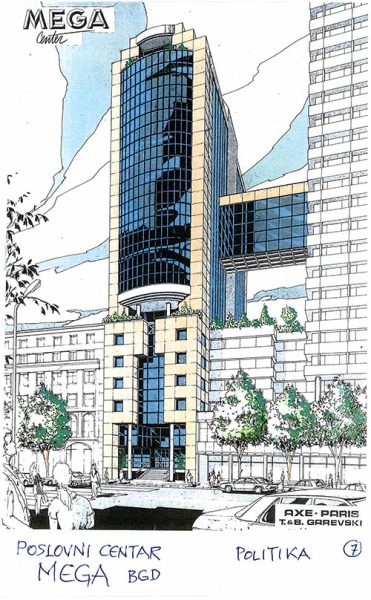

And how is it possible that Toma Garevski from Čubura has never done any work in Belgrade? Responding to that question, CorD’s interlocutor offers the following answer.

“I haven’t managed to implement anything concrete, but I have proposed many projects. First and foremost were several offices next to the building of Politika, where to this day there is still an empty space, or rather a parking lot. I proposed an office building opposite the Assembly, on the site where the Three Leaves of Tobacco tavern used to stand. I provided a project for the expansion of the hotel on Avala. I brought Mr Eric Hilton to Belgrade to explore the possibility of building a hotel. I’m currently working on a project for a hotel that will be located next to Nikola Tesla Airport in Surčin. I have a great desire to also leave a mark in my hometown.”