She has been a curator at two of Serbia’s largest museums, holds the title of professor emeritus and has authored hundreds of important studies, but also a dozen books and monographs. Thanks to her persistence and perseverance in her work, resulting in an abundance of valuable research results, one important avant-garde art movement from the early 20th century – Zenitism – has found its place in the history of contemporary art

It is unavoidable for any presentation of art historian Irina Subotić (1941) to begin with the saga of her family, because her origins and upbringing determined her life choices to a large extent. Born in central Belgrade just as World War II was reaching the country, she was baptised at the famous ‘Saborna Crkva’, the Cathedral Church of Saint Michael the Archangel, attended the King Petar I Primary School, resided in the Vračar neighbourhood for a while, then on Banovo Brdo, only to arrange with her husband Dr Gojko Subotić, who she married in the Municipality of Stari city, the penthouse apartment in which they still live. It can thus be said that her life’s journey has unfolded within the boundaries of old Belgrade.

Her half-Polish, half-Russian mother, Tatjana Lukašević, arrived in Belgrade in 1939 and married Irina’s father, Milivoje Jovanović, in 1940.

“Mum didn’t know Serbian, so she communicated with my dad in French. When I was little, my mother spoke Russian with me, but she stopped in 1948, due to well-known events [the Tito-Stalin split]. She carried multiculturalism within her and instilled it in me in various ways. When they were young, her mother and aunt formed a musical duo that was famous in Saint Petersburg during those years, and it was also said that Mayakovsky [Russian poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky] visited their home to attend their artistic evenings.”

The sister of Irina’s mother, after whom she is named, was a ballerina and actress. She played the female lead, opposite Vittorio De Sica, in the 1933 Italian film Bad Subject [Un Cattivo Soggetto].

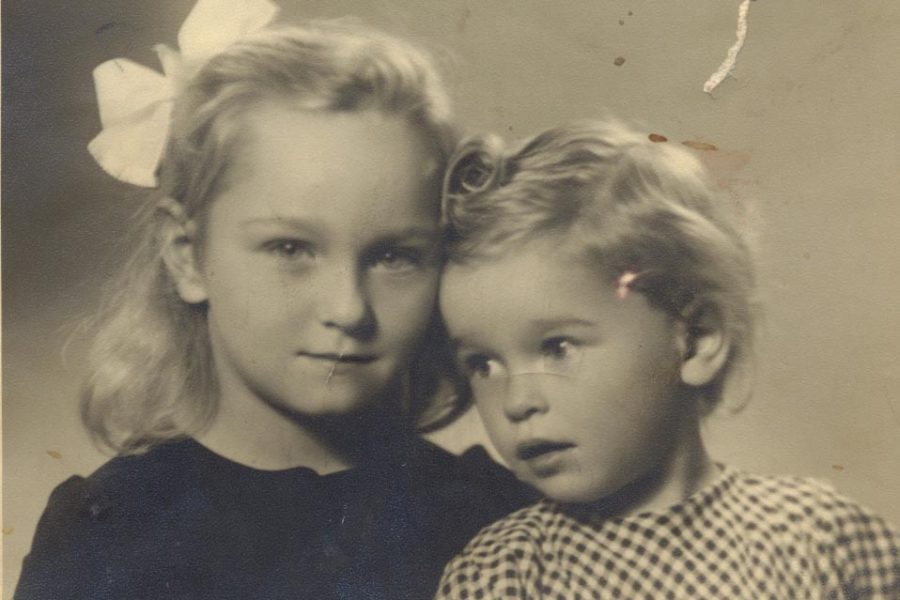

“My mother studied opera singing, but she abandoned her studies when she came to Belgrade to visit her parents, who had fled here because the city had a large colony of Russians. She met my father, they wed and I was born the following year, only for my sister Jelena to be born three and a half years later. My mother remained eternally stateless. She lost her nationality and, apart from falling in love with my father, she also fell in love with Serbia and all its traditions. That’s how we came to live with all Serbian and Russian customs.”

Milivoje Jovanović originally hailed from Krupanj in the Rađevina area. He graduated in law and worked for the City Administration. Advancing in his career, just before the outbreak of World War II he had been in charge of the civilian aides and security of Prince Pavle. And he advanced from that position to become chief of police for the City of Belgrade.

Only 30 per cent of what previously existed can be changed in a single generation, in order to preserve the spirit of a city and for it to have layers that make it valuable

“He saw what was about to happen and he had a large number of friends among Jews and leftists. He remained in the City Administration, but not in a leadership position, and until 1943 was responsible for many good deeds that I only learned about in the middle of the last decade. He never spoke about that, but thanks to the documentation of his good friend Miodrag Popović, the father of lawyer Srđa Popović [famous as a political activist and leader of the student movement Otpor (Resistance) in the ‘90s], I found out that he compiled lists of people who had been accused of wrongdoing under the regime and threatened with arrest and even death. Those lists reached members of SKOJ [The League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia] who rescued the suspects. The Germans grew suspicious of my father and the Gestapo ultimately arrested him. He was tortured in an electric chair and then transferred to the Banjica concentration camp, which had actually been established while he was chief of police! He was arrested several times after the war – the last time in 1948. We thought that was linked to Infombiro [the period of purges within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia], but we never discovered the truth. He knew how to keep his mouth shut. When I asked him how he survived the Gestapo, the Banjica camp and subsequent imprisonment, he would constantly repeat that the most important thing had been to say that he didn’t know anything: that’s how he saved the lives of hundreds of other people, but also his own.”

Irina’s father had socialised with famous painters of the time: Lubarda, Gvozdenović, Šerban, Peđa, Milunović et al. He had a nice collection of paintings that was split between Irina and Jelena after their parents passed away.

“And at the time he was in prison, everything in the house that could be sold was. Carpets, silver, even books… the pictures were last because they were my father’s greatest love. They both departed this world in a symbolic way: Mum died on Good Friday, 6th May, 1983. Dad couldn’t endure that loss and departed himself just a year later, on Friday, 18th May, on Saint Irina’s Day. That was the name day of both me and their granddaughter Irina Ljubić, Jelena’s daughter. Mum wasn’t even 70 when she died, while dad made it past his 70th birthday. She had been in very poor health in her last years, and the diagnosis we heard from one doctor was ‘Your mother has worn out her life!’.”

Irina’s younger sister was famous ballerina Jelena Šantić (1944-2000). Having succeeded professionally, she devoted the last decade of her life to the continuous struggle for peace on the territory of the country at war that was then still called Yugoslavia, but those wars took many victims and changed the faces of yesterday’s republics. She said: “I poured my despair and horror into concrete work against hatred, nationalism, chauvinism, para-fascism and violence… I experienced the outbreak of the war as the collapse of culture and our civilisation.”

Speaking about her sister, Irina says that she had known from her primary school days that she would be a ballerina.

“She had enormous energy while she danced, but also enormous life energy with which she fought and which, unfortunately, she also depleted with the illness that took her life at the age of 55. She left behind her daughter Irina, an art historian who had attempted to work in a state institution, but that didn’t suit the libertarian spirit that had been instilled in her by her mother. And then she did something great and important. She separated the fund established by Professor Vojin Dimitrijević in the organisation Group 484, which had been founded by my sister, and thus the Jelena Šantić Foundation was born. That Foundation now operates successfully and Irina holds on to the idea that the Foundation’s work will help to really improve things when it comes to young people and women, and to culture more broadly penetrating small communities… Irina has two wonderful daughters, our granddaughters, who are 18 and 11.”

I asked my father how he survived the Gestapo, the Banjica camp and subsequent imprisonment, and he said that the most important thing had been to say that he knew nothing

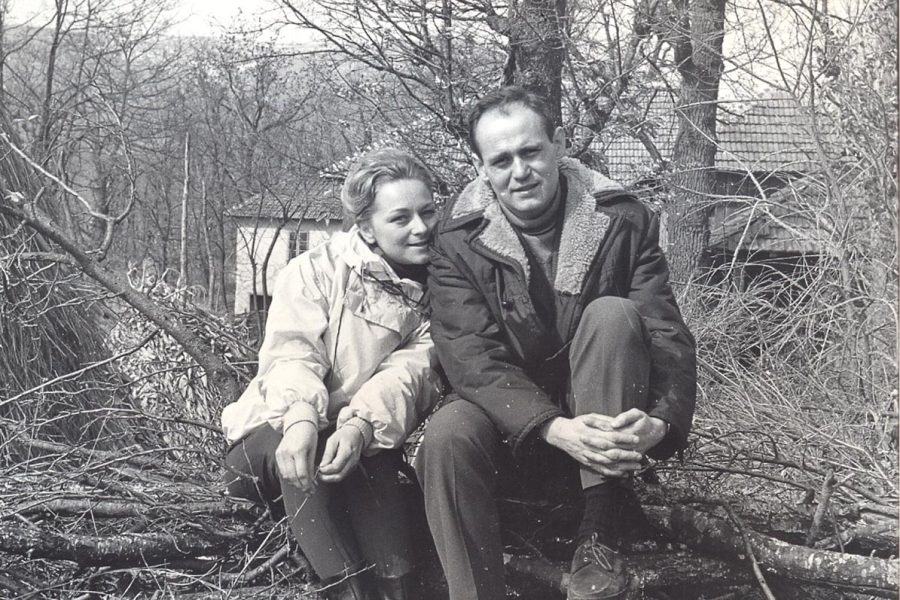

Irina’s husband is Dr Gojko Subotić. A historian of medieval art and full member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU), he is one of the most important and respected experts in the field of protecting monuments of culture. She says that she was ‘tricked’ into meeting him. In her third year of high school, for the final exam of the School for Tour Guides, she was tasked with walking through Belgrade to Avala and presenting all the monuments created by famous sculptor and architect Ivan Meštrović. Meštrović had previously published a memoir in which he criticised Tito, resulting in all books about him being withdrawn and hidden from the public eye. She searched for anything about Meštrović in various places without success, ending up at SANU, where she was offered a doctoral dissertation that was of hardly any use to her. Upon returning it, she didn’t know who had lent it to her, so she placed the business card that her father had made for her in the book. The young man to whom she returned the book with the business card was Gojko Subotić, and within a year and a half the two of them were married. They spent the most beautiful year and a half living in Greece, when Gojko was learning the Greek language, before returning to Belgrade and sharing an apartment with his parents.

They have two daughters, both of whom abandoned Belgrade during the 1999 bombing of Serbia.

“We weren’t aware that that would be permanent, but they quickly found their way and established their own families. Our elder daughter, Jelena, received a scholarship for postgraduate studies in America, earned her doctorate and is now a professor of political science at Georgia State University in Atlanta. She is married and has a wonderful seventeen-year-old son. Our younger daughter, Ivana, graduated in Italian Studies and lives in Rome with her husband. After numerous different jobs, she’s been working as a manager of apartments over recent years and is very satisfied with her work. Their son is a student of modern gastronomy and hotel management.”

There’s no doubt that the upbringing Irina received at home also determined her profession. She grew up surrounded by paintings, serious music, books… She read a lot and attended exhibitions and concerts. She was very close to her father.

“He was a gentle, wonderful father. It was from him that I received knowledge and a joy of life, but I also remember the sadness he carried within him. We lived at 2 Braće Jugovića Street, opposite Glavnjača [the colloquial term for a political prison in Belgrade city centre]. When he was in prison in 1948 and would go out for a walk with all the other prisoners on Fridays, I would watch him from the roof of our building, together with my mother and sister. I was seven at the time. When they later relocated us to Beogradska Street, the din of the tram would wake me up at night and I would fear that something had happened to my father… His imprisonment was terribly traumatic for me. Fortunately, my parents didn’t ‘poison’ me or my sister with what dad had gone through.”

The issue of culture has failed the test in all fields in our country, and perhaps most of all in museology, because we don’t keep abreast of what the civilised world is doing

Milivoje attempted to convey everything he knew to Irina. They would walk around Belgrade so he could explain to her how the city had looked prior to the bombing of 1941 and 1944.

“My mother instilled in me a different kind of love for art, and thanks to my knowledge of her language, I earned money as a translator and tour guide when I was a third-year high school pupil. I used the first money I ever earned to buy the Herbert Read book The Meaning of Art. I read it all night and realised that I wanted to study modern art, because there were many more meanings hidden behind the appearance of beautiful colours that I wanted to discover.”

Over the last 25 years, or more specifically since the death of her sister Jelena, Irina has been recording the genealogy of the Lukašević and Jovanović families, but also the Subotićs. Her work has today evolved into a huge book of nearly 800 pages that’s intended for children who aren’t in Belgrade, as a recollection of memories they don’t have.

Irina’s professional life implied constant work and study. She was ultimately awarded an Emeritus Professor title, while life taught her to be strict.

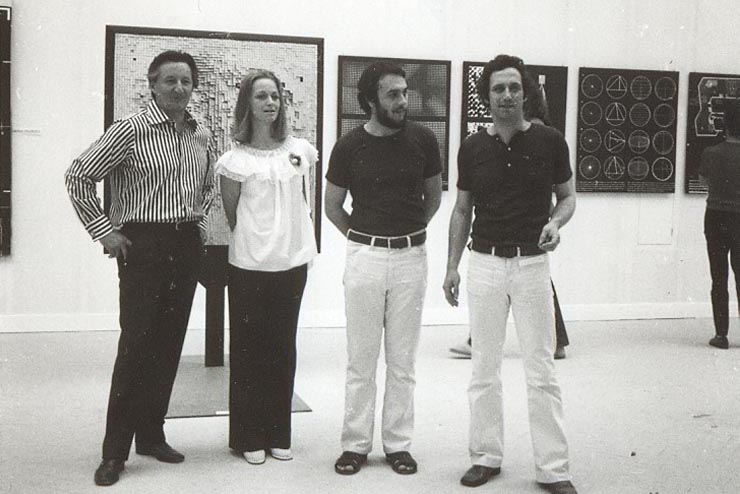

“It was only in my later years that I learnt to dismiss that seriousness a little; to be a little more lenient towards myself and others. I learnt from the great art historians and the good artists in my surroundings that, when it comes to art, the testimony of an authentic creator is very important in our profession. I left behind many traces of their words; I wasn’t a so-called ‘first-person critic’. I started writing early on, thanks to Stojan Ćelić, who established the magazine Umetnost, together with a group of other intelligent people, and invited me to contribute. I didn’t include my own theory in the articles, nor did I rely on aesthetics and citing greats. I learnt from what I discovered by socialising with people from the art world; I wanted to be cognisant of how authentic and variegated they are in their poetics; I wanted to get better acquainted with their work and then better acquaint others with it. That’s why I wrote numerous articles about great artists who have remained great and inimitable to this day, such as Leonid Šejka, Cuca Sokić, Vladimir Veličković, Milenko Šerban, Stojan Ćelić and others. Of course, I also wrote about many artists who were just emerging on the scene and who invited me to write about them. I didn’t hesitate to use my words for the sake of artists who didn’t have a major biography or a prominent place in the art world. These weren’t about praise; I wasn’t dealing in epithets, but rather the meaning of their work, in the case that I found such meaning. And there were many articles that I had no desire to write…”

When the Museum of Contemporary Art opened on Ušće in 1965, it represented a new wonder of the world in terms of architecture and the museology concept provided by its founder and first director, Miodrag B. Protić. And CorD’s interlocutor explains that this was no accident, but rather a consequence of state cultural policy. On the other hand, today, unfortunately, even following the National Museum’s restoration just a few years ago, this national institution still isn’t capable of hosting a single globally-relevant exhibition, because it lacks the required technical conditions that are a given for major museums. Irina is the best possible witness to the good and bad times of these museums, having worked as a curator at both of them.

We can no longer have major exhibitions at the National Museum like we used to. Conditions have changed around the world and we haven’t adapted to them

“Yugoslavia firstly wanted to be relevant in international circles at the cultural level, and not only in the policies of nonalignment. It also wanted to carve out a more stable place among the countries of the developed world, to which it wanted to belong. Then there was Miodrag B. Protić – who was extremely influential with his vision, despite not being a member of the Party. Those were years when culture was deemed important and necessary. That’s how, even during the 1980s, the National Museum still inherited that which Lazar Trifunović had established back in the 1960s as the vision of a great Museum. He was the first to bring us works by Van Gogh, to make agreements with the most important Dutch and German institutions etc. With his considered policy, the National Museum stimulated a high level of expertise and brought proven treasures. And then came the ‘90s – disastrous in every sense: not only because of the countless dead and displaced persons, because of the destruction of Yugoslavia, but also because all values dropped, such that an inconsequential painter could be the director of the Museum of Contemporary Art for an entire decade and sweep away almost everything that Protić had done. When the need was felt in the early 2000s to transform the National Museum into a museum of worldwide relevance, which it deserves to be thanks to its priceless collections, and it was realised that this would entail major reconstruction works, digging underground spaces and building extensions, animosity and our mentality let to that being abandoned, so we ended up with only painted rooms. That’s why we can no longer have major exhibitions like we used to. The truth is that conditions have changed around the world and we have been left behind, having failed to adapt to those changes. The issue of culture has failed the test in all fields in our country, and perhaps most of all in museology, because we don’t keep abreast of what the civilised world is doing.”

When asked, in her capacity as an art historian, if it’s normal for a city to undergo so much demolition to make way for large apartment blocks, as we see happening in Belgrade city centre, Irina explains: “Only 30 per cent of what previously existed can be changed in a single generation, in order to preserve the spirit of a city and for it to have layers that make it valuable. That’s how it was done in Lisbon and Buenos Aires, and those are referred to as preserved cities. There are derelict buildings in our country that need to be demolished, but the problem is that investors, rich people, are building at a hitherto unseen speed as if they’re just laundering money, paying no attention to the entirety, to the residents, to history, tradition, everything that comprises the spirit of a city. All that matters to them is to build whatever they want, in locations with the highest rents. And the institutions that should take care of this and prevent destruction – from the National Assembly to the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments – don’t function properly.”

It was thanks to Irina that the valuable art collection of Zenitist Ljubomir Micić was saved from oblivion. That marked the start of the broader recognition of Zenitism as an authentic avant-garde movement, thanks once again to this exceptionally capable and charming woman.