His name is synonymous with success in this part of Europe, while his theatre plays are the best part of the history of Yugoslav theatre. Born in Sarajevo, this cosmopolitan, philosophical anarchist and anti-fascist never stopped believing in and fighting for the Yugoslav cultural space. He says that Yugoslavia was the happiest part of his life and that sometimes it seems to him that the international community has one plan for Bosnia-Herzegovina and for Serbia – controlled crisis… Forever.

“Yugoslavia was my country. It was a concept of the world in which I was born and raised, and in which I formed as a man and an artist. That country had some significant problems, but it had a lot of good things. One of those fantastic things was that common cultural space, which was so powerful that even today, after the horrors of war, that space still exists,” he notes naturally.

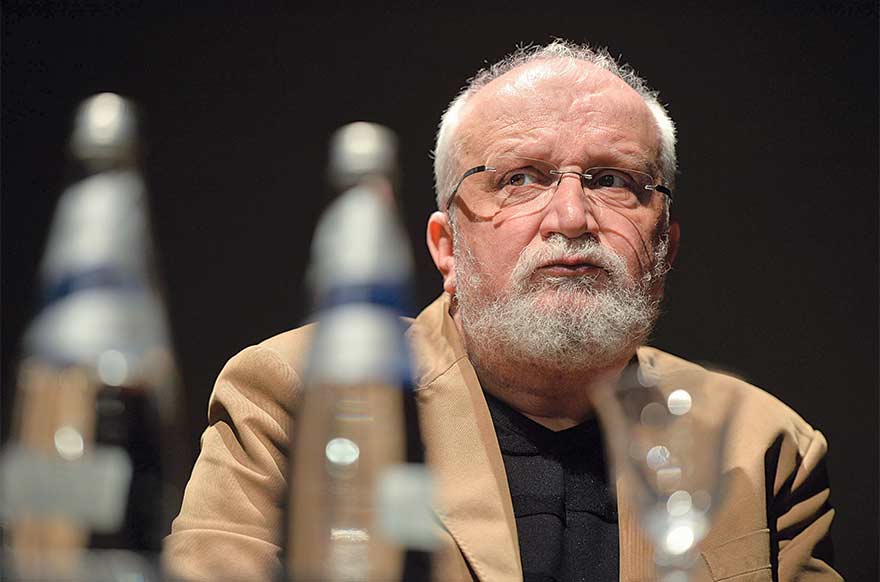

I choose these sentences of Haris Pašović (59), theatre director, professor and one of the most successful artists in this part of Europe because they are an unavoidable stamp from his ID card. Just like the following:

“Recently, after the earthquake in Zagreb, Sarajevo-based illustrator Midhat Kapetanović drew Vučko carrying an injured Zagi over the ruins. A few days ago, someone continued that motif during the demonstrations in Belgrade, with a drawing in which Zagi and Vučko defend the injured Victor. Shortly afterwards, during the time of commemorations of the Srebrenica genocide, the three of them together “came” to Potočari, to the memorial centre.

“Well, now: Vučko was created by Jože Trobec, a Slovenian artist, as the mascot of the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. Zagi, the mascot of the Zagreb Universiade [1987], was originally created by Nedeljko Dragić, an artist of Serbian origin and the Victor (Pobednik) monument was a work of Ivan Meštrović, Croatia’s greatest sculptor. In one picture, in the third decade of the 21st century, they were combined by Midhat Kapetanović, a Bosniak artist. The fact that we understand this story, and that it awakens emotions in us, and that foreigners cannot understand either the story or our emotions, testifies to the uniqueness of our cultural space.

“Yugoslavia was the happiest part of my life.”

Right up until the outbreak of the wars of the 1990s, Pašović thought that his upbringing had been completely normal. He was born in Sarajevo and lived in a typical Sarajevo street in the city centre, where the houses and apartments were just like those in the classic story of Sarajevo – one Muslim home, one Orthodox, one Catholic, one Jewish, one atheist, one mixed marriage, and the same again… Literally. Moreover, as in every Balkan family – half of the members are believers, half are atheists. Communists against capitalists in the same family, believers against infidels, football fans of Sarajevo against fans of Željezničar, constant debates, and yet everyone eating, drinking, celebrating and hugging together:

“Classic Balkan charming bedlam. My family was also like that. In the neighbourhood, Aunt Divna always brought dark red eggs and beautiful bagels for Easter, the likes of which I didn’t eat in Serbia when I later lived in Novi Sad and Belgrade; for Catholic Christmas, we went to my aunt Elfrida, an Austrian lady, and to our Catholic neighbours, for Eid al-Fitr [feast marking the end of Ramadan] Qurban sacrifice meats were distributed around the neighbourhood, and alongside all of that there was communism, and everything was somehow harmonious. It’s not that I’m sentimental, I’m really not, but it was really interesting to grow up like that. It was equally multicultural at school, everywhere… We didn’t have the word ‘multicultural’ in our dictionary until 1992. It was all ONE culture. Then foreigners literally imported the word ‘multicultural’ into our language.”

His parents Reuf and Nadžija gave their children, Haris and Lejla, love and taught them honesty. His father died young, of a heart attack, at the age of 57, and he was very proud of Haris’s successes. His mother wasn’t satisfied with her son’s choice to be a theatre director, regardless of his successes. Haris’s sister Lejla is a professor of literature by education, but an artistic producer by profession and she works at the American Embassy in Sarajevo. The two of them are great friends who support one another. Their mother nurtured in her daughter a trait that could be dubbed practical feminism. When Lejla got married, she told her future son-in-law:

“She doesn’t know how to do anything in the house, so don’t expect anything from her”. On the other hand, she taught her son that it is normal to put things away behind him, to wash his dishes after lunch, and also to cook. Lejla has been married for more than 20 years to director Dino Mustafić, they have a daughter Iman.

Haris recalls his childhood as being beautiful:

“In the summers we went to the Adriatic, stopping in Mostar to see the Old Bridge. Every year it was like that as if we hadn’t seen it the previous year, and the year before, and the year before that. In the winters we went to Jahorina, Bjelašnica, Trebević and Igman, after 1984 they became the Olympic mountains. Everything was normal for me, including the bridge on the Drina, the Sarajevo assassination (my grandfather heard the shots), Yugoslavia, and the battles on the Neretva and Tjentište.”

Yugoslavia was my country. It was a concept of the world in which I was born and raised, and in which I formed as a man and an artist.

From the third grade of high school, directing was his only choice. He graduated from the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad, in the class of Professor Bora Drašković. He was also educated in the U.S., Denmark and France.

Pašović has been one of the leading theatre directors in Southeast Europe for more than three decades. He is a full professor of Theatre Direction at the Academy of Performing Arts in Sarajevo and a professor at the IEDC Business School in Bled, Slovenia. He is the artistic director of the East-West Centre in Sarajevo. He has worked all over the world and still does so, but he never left Sarajevo:

“Under normal circumstances, I live in Sarajevo for less than five months of the year, because I work in Italy and travel a lot around Europe, the Balkans, the world. I completed my studies in Novi Sad, lived and worked in Belgrade, and if there had been no war I wouldn’t be living in Sarajevo. I studied in America and Denmark, then lived in the Netherlands and Sweden. I travelled for years after the war, often every week in a different city, or a different country.

“Sarajevo is dear to me, it has a certain charm and energy that I like very much. In Sarajevo, I like that people are cordial and witty. The food is great. There are many talented and inventive people. The multicultural mosaic is still the essence of this city and I like that because I’m essentially cosmopolitan.

“Perhaps in the future, I’ll live in Belgrade. Belgrade is the only metropolis in the Balkans, along with Athens. Belgrade has now returned to its urban, fine form, after the hellish collapse of the 1990s. It still lacks a more international dimension. I will either live maybe somewhere by the sea or maybe in some other European city (I adore Paris and love Madrid, London, Berlin). I like big cities, metropolises.

“My education, like all of us who grew up in Yugoslavia, was cosmopolitan. I began very early on to feel the whole world as my home, my homeland. In high school, I travelled around Yugoslavia with friends, and in college, I was already travelling around Europe, often alone. America, Africa and Asia had their turns a little later. I’ve been to America more than 20 times. I adore Asia, the people, food, art, that vitality, life energy…”

We didn’t have the word ‘multicultural’ in our dictionary until 1992. It was all ONE culture. Then foreigners literally imported the word ‘multicultural’ into our language.

In the case of this artist, his success story is quite simple: success has been a normal thing for him since he’s known himself. He completed ‘gymnasium’ high school in three years; in the second year of his studies he began directing professionally; the play for his third year exam “Jelka kod Ivanovih” [Christmas tree at the Ivanov’s] was among the winners at the MES Festival in Sarajevo and participated in the Belgrade International Theatre Festival – BITEF. At the age of 25, he created the play “Awakening of Spring”, for which he received the Politika Award for Best Director at BITEF (the award had previously gone to Ingmar Bergman, Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, Bob Wilson, Peter Stein et al), at the age of 29 he founded the study course for Theatre and Film Directing at the Sarajevo Academy.

Haris’s plays have participated in major programmes of the world’s largest festivals, including the Edinburgh International Festival, Festival d’Avignon, Singapore Arts Festival… They have been performed in around 20 countries on three continents; Peter Brook gave him his own study to work in when he spent three weeks as a guest with his plays at Brook’s Parisian theatre, Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord; his documentaries have been screened at the Lincoln Centre in New York and the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm… He is invited to speak at eminent gatherings from Shanghai to New York, St. Petersburg to Helsinki, and Brussels to Barcelona:

“I’ve never measured success with money, but I earn well and live nicely. I’m not interested in wealth or great property ownership. It was equally nice for me to spend summer in the most luxurious hotels in the world, such as the Oberoi in Bali, but also in wild camps on Lastovo and Mljet [Croatian islands]. I’ve socialised with people from the market, but also with presidents of states; with novice artists and with world stars.

Sometimes I turned out to be ridiculous. Once, in New York, Vanessa Redgrave introduced me to a tall man and then disappeared somewhere. The two of us started some conventional conversation, I asked him what his name was and what he does. He said: “Christopher Reeve, actor”. That’s when I realised it was Superman, one of the most popular actors on the planet at that moment! However, my greatest success is that throughout all these years I’ve remained a simple, honest and just man.”

He is proud of his directing and the fact that he never made compromises. Frank Wedekind’s play Spring Awakening was a wonder that is still talked about today. When he entered the hall for the reception after the premiere, Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz, Bata Stojković and Dušan Kovačević got to their feet. They were classic actors of Yugoslav and Serbian drama and theatre, and he was 25 years old. Mihiz said: “This is the biggest entrance to Belgrade theatre since Boro Drašković!” And Boro Drašković was his professor:

“I am also proud of Dozivanje ptica [Aristophanes’ The Birds] (Yugoslav Drama Theatre) – we made an amazing show at the institution, and we worked for nine months as if we were some big world company; Waiting for Godot (Belgrade Drama Theatre) – literally the last Yugoslav premiere, performed on 25th June 1991, during the break we heard that tanks were heading for Slovenia, so the first act was performed in Yugoslavia and the second in a collapsed Yugoslavia; In the Country of Last Things by Paul Auster (MES Festival during the siege of Sarajevo); Hamlet, Europe Today, Faust, Class Enemy (East-West Centre); Conquering Happiness (British Capital of Culture) etc.”

Those years in Sarajevo under siege represent the most important part of my life, which I wish hadn’t happened

However, the most touching, something that was very special for him and the world, was a project beyond all categories – “Sarajevo Red Line” – a concert/installation for the 11,541 citizens of Sarajevo killed – with the same number of red chairs placed along a kilometre of the main street M. Tito in the centre of Sarajevo:

“That’s a project that transcended the whole city that day, hundreds of thousands of people came to visit the installation, the whole world reported on the event, it was incredibly touching, moving, but also somehow cathartic.”

There are many great moves in Pašović’s biography, when he proclaimed himself an artist and a citizen in defence of art and human dignity, fighting for justice and truth. However, the most honourable moment was when he arrived in Sarajevo while the city was under siege:

“I was in Subotica when the siege of Sarajevo began and I couldn’t return. I went to Amsterdam to stay with Dragan Klaić and his wife Julija Bala, for one week, ‘until those riots settle down a bit’. I couldn’t return for months, I got a job – directing the opening of the cultural capital of Antwerp in 1993, but I couldn’t work. As it wasn’t possible to take the normal route to Sarajevo, I managed, in very complicated ways, to enter a besieged Sarajevo for New Year 92/93. I led an art festival in the besieged city, produced Waiting for Godot, which was directed by Susan Sontag, directed plays, founded the Sarajevo Film Festival… That all made sense, and I’m proud. I was what Hemingway, Orwell and Akhmatova were… I didn’t betray my role models. Those years in Sarajevo under siege represent the most important part of my life, which I wish hadn’t happened. War is horror and only horror. The fight for freedom is good and inspiring, but war is a disaster for everyone. There is absolutely no one who can emerge from the war unscathed.”

CorD’s interlocutor is among the greatest enthusiasts who don’t stop believing in the existence of the cultural space created in the former Yugoslavia:

“It exists. The nationalists would have destroyed it if they could, they tried, in some places they succeeded a little, but they couldn’t destroy it as a whole, because it is natural. The ties between people and cultures are so complex and strong that it is not possible to break them in the foundations. The most profitable investment in the Balkans is an investment in that common cultural space.”

When he defines his political beliefs, Haris says of himself that he is “at heart a philosophical anarchist, which means that I believe in a responsible, free man without a state. In the real world, I know that we’re still a long way from that. I am essentially a democrat. And an anti-fascist.”

He describes the political situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina as:

“Controlled crisis. It would be very bad if the intention of the international community is to keep B-H in this ‘controlled crisis’ for a long time. Sometimes it seems to me that this is the plan for both B-H and Serbia forever.

“The biggest problems in the countries of the former Yugoslavia are a lack of essential democracy and healthy, modern political forces; and unemployment. That is used by various extremist groups to get rich. The results are disastrous. Compare Yugoslavia 25 years after World War II and the current states that emerged from the collapse of Yugoslavia – in 1970 the standard grew; political liberalisation began despite state resistance; culture developed; the country advanced in terms of infrastructure; there was no unemployment; progress was visible in science, education and international politics…

Now there is high unemployment everywhere, the consequences of the war are still visible everywhere; culture, science and education are collapsing, we have no kind of political reputation in the world. The blame for all of this lies with extremist policies and interest groups.”

The ties between people and cultures are so complex and strong that it is not possible to break them in the foundations

Another artist who symbolically represented the former Yugoslav space was the young Igor Vuk Torbica, who took his own life this summer at the age of 33. Haris invited his play Hinkeman to the Mittelfest festival, of which he is the artistic director in Italy, and the play Tartif to the Sarajevo Fest Art and Politics festival, of which he is also the artistic director.

And he wrote for weekly magazine NIN a very touching and admonishing farewell for his colleague, whom he says was “a great director, a very interesting interlocutor and an impressive man”. When asked if there is an explanation why it is so disastrous for a young man to show weakness today, what is bad in today’s value system, in harsh competition between young people, Pašović answers:

“When I was young it wasn’t considered something bad if you showed that you were vulnerable. Today’s everyday life is so brutal that young people mustn’t show the slightest weakness, because others will destroy them. Today you mustn’t say that you’re in a bad mood, sick or that you are simply having a ‘bad day’ – that is immediately interpreted as if you are a loser, incapable of dealing with harsh reality. Young women are afraid to get pregnant because their employers will fire them. You must constantly project the image that you are in full working capacity, that you are rich, that you enjoy life; you must post pictures on Instagram that show that you are great, that you feel great, that everything is great, that it will be great… It is an abnormal reality that does not correspond to the political, economic, social or personal reality in which these young people live.”

And Haris analyses the reality in which we live as follows:

“Authoritarian forces are increasing their pressure, which means that they feel insecure. And that’s a good sign because authoritarianism destroys society. On the other hand, it is becoming clear that there are no healthy political forces that can articulate the great dissatisfaction of people, especially young people and those who are unemployed or have low salaries. It is to be expected that modern young politicians will emerge who will shape these modern interests of the majority of citizens. This will create a new political and social dynamic, which will force the existing political forces to modernise and reform. The climate; biological challenges (infectious diseases, bioterrorism); economic restructuring; legislation that arises from new planetary circumstances; the development of technology; new art – these are the topics of the future for which we must all prepare. That future has already begun.”