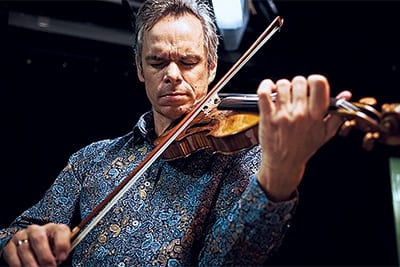

One of the most versatile contemporary violinists, Benjamin Schmid, speaks exclusively to CorD about his life, which he says is “more important than a career”. A particular strength of his can be found in his exceptionally broad repertoire and very personal style. At the core of his career are works by Austrian composers like Berg, Goldmark, Korngold, Kreisler, Mozart, Muthspiel, Schoenberg and Webern

As one of the greatest violinists of our time, Benjamin Schmid (50) visited Belgrade in April to perform with the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra, playing Tchaikovsky’s famous Concerto for violin and orchestra in D major op. 35 at Belgrade’s Kolarac Endowment Hall.

The audience was thrilled with Schmid’s distinctive ability to project his superstar appeal in interpreting one of the most fascinating pieces of classical music while remaining an artist with human warmth. We found him between rehearsals with the Belgrade Philharmonic, on the day of the concert, discuss-ing Mozart, ironing shirts and old violins. This was a unique opportunity for the conversation that we are now relaying to you, CorD’s readers.

You are followed wherever you go with the reputation of a superstar of classical music. That must be flattering, but perhaps also overwhelming. What is your opinion about this kind of promotional label that is more common in the worlds of rock music, Hollywood, fashion… Does it help classical music to enhance its visibility and increase audience numbers?

Classical music is way behind rock and pop music, and way, way behind sports, so I think that the more classical music can get into the centre of the attention of society, the greater audiences it will win over.

We never had audiences as big as we have today, never as many concerts.

Classical music is, in my opinion, one of the most significant achievements of humankind ever, and a lot of people agree with this statement. Education is also growing, but the big gift is heritage – music is one of the greatest inventions ever made by humankind. Anyone who has access to the world of classical music is going to be enchanted! I am definitely in favour of the popularising of classical music, growing audiences, including open concerts, but I also believe that music has to have the right frame, especially in an acoustic structure. So, we should do everything to expand audience figures – classical music has a bright future – we must keep it interesting by allowing new music to venture into classical music. Otherwise, we’ll end up in the funny museum, and we do not want that, do we?

Regarding the reference to me as a “super-star”, I know it’s part of the business, but, for me, life is still more important than my career limelight. My career is crucial to me, but it is not easy at all to find the right balance and handle constant pressure. To become great, you have to confront that pressure.

Classical music is, in my opinion, one of the most significant achievements of humankind ever, and a lot of people agree with this statement

You were born in Vienna and raised in Salzburg – two cities that are important to the culture of European music in many aspects. How did these cities influence you, and what would you define as the strongest and most authentic impulse of music emanating from these two cities?

That must have been Mozart, who was a native of Salzburg who then lived in Vienna, which is the opposite to what happened to me – I was born in Vienna, while I now live in Salzburg. I grew up with Mozart – he was one of the great geniuses of music, a talent of the millennium, and music came to him effortlessly. The way he seems to have put things in place appears so natural and spontaneous. He had the desire for organisation, for order, for clarity, and all of that falls into place. We grew up with this kind of phenomenon. He was a central figure in my musical upbringing, but that upbringing was not confined to Mozart.

At the turn of the last century, Vienna experienced the most exciting period in classical music. Prior to that, Vienna had the greatest musical minds, with Mozart, Haydn, Schubert, Brahms and even Beethoven all spending most of their lives there. Vienna has the planet’s strongest music scene. It’s an incredible place for music, and I spent my student years in the Opera and Musikverein concert hall. At that time, you must remember that the Alban Berg Quartet had eight double concerts with the best string quartets in the world, and a waiting list for subscription ticket holders! That illustrates how central music is for the heart of society in Vienna, and it is quite incomparable with anywhere else. Viennese people love music.

Vienna also gave us the most important innovations in the history of interpreting classical music.

What is your routine like when you’re touring; with concerts tightly scheduled one after another almost every day, how do you preserve your vitality? Do you have a particular habit that you practise before a concert?

It becomes more important as you age that you take care of things. When I was 20, I practised all the time. Today I still practise a lot, but it is more mentally – I might be with an instrument for three hours a day, while there are many days when I practise for eight hours – but three hours is enough to go through the repertoire. I always try to eat something substantial about five hours before a concert. Another ritual for me is to iron my shirt myself before a concert. The thing with ironing is that you can’t hurry, you must take your time to do it properly, so it is a kind of meditation… What you try to do that is sometimes challenging is to save your energy before the concert; to save it for that moment, at eight o’clock, when you have to do everything right. It’s important to be able to store your concentration, output and emotionality.

I grew up with Mozart – he was one of the great geniuses of music, a talent of the millennium, and music came to him effortlessly

How important is a good instrument for achieving faster progress or achieving one’s musical vision? You perform on one of the best Stradivarius violins – an “ex Viotti” from 1718. What can you tell us about its origin?

I play on a Stradivarius violin from 1718, which means it’s 300 years old, and I’m 50, so we are celebrating our anniversaries together. It is an “ex-Viotti” instrument, and Viotti was the famous Italian violinist who made the premiere performance on it during the time of Mozart, after which renowned Austrian violinist Arnold Rosé, who spent half a century as concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic, performed on this violin for 50 years. It is now under the ownership of the Austrian National Bank, and I am happy to have it on loan.  I have played many Stradivarius violins in my life, and this is one of the best when it comes to purity of sound and clarity of modulations. I feel very blessed to be able to touch this instrument every day. When I tune the strings, it is already miraculous; I don’t know where this sound comes from or how it was possible to produce such an instrument 300 years ago…

I have played many Stradivarius violins in my life, and this is one of the best when it comes to purity of sound and clarity of modulations. I feel very blessed to be able to touch this instrument every day. When I tune the strings, it is already miraculous; I don’t know where this sound comes from or how it was possible to produce such an instrument 300 years ago…

On the other hand, I am a great fan of modern instruments – but for a specific repertoire and special hours, the Stradivarius is just totally un-beatable, and brings tears to my eyes immediately. You have to find an instrument that responds to your abilities and you as a person. And maybe the most important questions of all are how I relate to my instrument and does it really relate to my playing; can I express what I am able to deliver on my instrument because every finger and every hand is different – and how do I feel my instrument? That is even more important than the absolute quality of the instrument. You want to get inspired as a musician – and the instrument has to be your unconditional partner.

Apart from your professional career, you are also a wonderful father to your children. How do you and your wife – a fellow musicians in pianist Ariane Haering – take care of your family life? Have your children started practising and are you happy for them to do so – considering how demanding the life of an artist can be?

I am fortunate to have four children and a pianist wife. Kids grow so fast … and we have our own castle of love at home. My wife refrained from playing a lot when the kids were young, and that is the great sacrifice she made, and I was basically freed to do a lot and some of the most important things in my career during that time – and that is only possible if you have a team, and that team was made possible by my wife. She is now playing more, as the kids are in school, but we are constantly struggling over who has to do what with which kid every day. When I am at home, which is more than half the time, I try to be there for the kids, and we spend quality time together.

The kids are the most important thing in our life now – we raise them with music and they have to learn an instrument or two, that is part of the deal in our house – of course, they don’t have to become professional musicians, because we know how difficult and complex that can be – but they want to have access to music and they do, and they play music and quite a lot of it. We play together, and you cannot express the feeling of playing with your own kids. I go home tomorrow and can’t wait to see them.

At your Belgrade concert, you will perform a famous Violin concerto by Tchaikovsky with the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra – announcing one more classical, fresh and sober version. What does that mean precisely, and how do you see the interpretative direction of understanding this great piece; why do you think it is necessary to go back and reinterpret its original form?

I’m not saying that tradition did any damage to the piece. It is over a hundred years old and is quite difficult, but it has been performed worldwide and has become one of the most popular pieces. Of course, it is by a Russian, but I must remind everyone that it premiered in Vienna, which makes us very proud. Tchaikovsky can appear more classical than we think if you look at the setting of the orchestra, the combination of instruments and the writing of the score. It is very effective and reduced to what is necessary. I was looking at the score for years, and a new interpretation with a few changes is now available, and it is also original. I like that kind of classicistic approach – we try to take a sober look at it, and I think the emotion gets even stronger. Take from what is there and profit from the great ideas of tradition, clean up where necessary, find your statement towards the score and period of music history, which is eternal anyway. But if we look at the qualities of Tchaikovsky and his incredible potential of making long, dramatic developments – that is why I like him because he can sustain tensions for such a long time and cause them to explode, and I love to explore this and go in that direction as long as possible. This is my approach, but it took me quite a long time to figure it out, three decades in fact, but it is the quality of a masterpiece – it is a learning process for a lifetime.

I was looking at the score for years, and a new interpretation with a few changes is now available, and it is also original. I like that kind of classicistic approach – we try to take a sober look at it, and I think the emotion gets even stronger. Take from what is there and profit from the great ideas of tradition, clean up where necessary, find your statement towards the score and period of music history, which is eternal anyway. But if we look at the qualities of Tchaikovsky and his incredible potential of making long, dramatic developments – that is why I like him because he can sustain tensions for such a long time and cause them to explode, and I love to explore this and go in that direction as long as possible. This is my approach, but it took me quite a long time to figure it out, three decades in fact, but it is the quality of a masterpiece – it is a learning process for a lifetime.

The Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra is excellent, but I have to say that 80 per cent of musicians in orchestras in this part of the world are over-qualified

The Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra is excellent, but I have to say that 80 per cent of musicians in orchestras in this part of the world are over-qualified. We are now dealing with the incredible potential of professional musicians, and smart ways of preparing and strategizing our energy before a concert. When I practised with the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra yesterday, I witnessed them playing incredibly at the rehearsal, but they still reserved some of their strength for the concert. We now have smart ways of preparing for a concert. Everybody knows how to do it, but it is the challenge of the moment that you have to deal with; the fact that you have to perform on stage with improvisation as if this is the first or last performance ever – otherwise the music does not come to life. It is our duty to deliver it like that, and I felt that every member of the orchestra was doing their best to be ready for that special moment of the concert.