Impressive, spectacular, colossal, ingenious – these are the words most often used by critics and audiences alike to describe his contribution to the theatre plays and operas that he’s worked on over the last ten years in Europe, mostly in German-speaking areas. He is today undoubtedly Europe’s leading stage designer, with his successes marked by his collaborations with famous German theatre director Frank Castorf. The two of them marked this theatre season in Belgrade with the play The Divine Comedy, which they staged at the Belgrade Drama Theatre.

The ancestors of Aleksandar Denić (59) were educated, dedicated to sport and the arts, mighty in their work and wealthy. The first mayor of Belgrade, Pavle Denić, was the uncle of Aleksandar’s grandfather and a civil engineer by profession. His granddad’s brother, Miomir Denić, was a set designer for theatre and film. His Granddad Jezdimir and father Miroslav were both architects. Together with famous Russian-Serbian architect Nikolay Petrovich Krasnov, Jezdimir did the work on a large part of the interior of the National Assembly, which served as the Federal Assembly for decades. Aleksandar’s mother, Mira, worked at the Faculty of Medicine, though she was extraordinarily gifted in drawing. CorD’s interlocutor describes them as a family of people who expressed themselves within the framework of ‘three-dimensional action’. And actually, his wife, Bojana, is also a great artist when it comes to translating from the German language to Serbian. She is editor of publishing company ‘Radni sto’ [work desk], which deals exclusively with the publishing of translations of literature from the former East Germany.

His upbringing in the home adhered to the standards of what represented the basis of a traditional civic upbringing. That “good upbringing in the home” implied freedom of choice, but also respect for norms that he never renounced. However, as he himself notes, “the older I get, the more often I conclude with my friends that today’s in-home upbringing is what makes us inferior compared to the ruling system of education. A good upbringing is today a handicap. I received an upbringing that was a mix of deeply rooted values from what used to be a civic stronghold, a street upbringing, a military upbringing…onto which self-governing socialism was grafted. In that socialism, decorations and adornments were removed from pre-war façades, in order to ensure they didn’t serve to remind of the past, just as they cancelled the excessive decorum that interfered with the new value system. Nonetheless, everything that then seemed to negate many of the virtues of civil society represented something of a swan song and honey and milk compared to what we’re seeing today.”

In the house of the Denić family (Aleksandar grew up with his brother Ivan), the basic principle of social life demanded that you show solidarity with your friends, with other people. That wasn’t a socialist principle, which the then government promoted equally, but rather an obligatory part of domestic upbringing from the youngest days:

Das Opernglas: if an Oscar existed for opera scenographers, it would undoubtedly have gone to Denić four times. It is also a powerful demonstration of the strength of the drive of Bayreuth Festival

“I don’t know how to separate the rage of helplessness today when I see how people focus rapaciously on themselves, almost exclusively. These are people for whom the only important thing is to satisfy their own desires, which can be reduced down to designer clothing, luxury cars, houses etc. They don’t look to see what’s happening around them, they don’t look to see if some talented young man close to them needs help.”

Aleksandar started playing ice hockey at a very young age and that love has stayed with him to this day. The ice rink at Tašmajdan is only around 50 metres from his house and he still loves the sport. He has long been playing it as a veteran.

“Even today, I plan my obligations around the schedule for our matches. And the days we play are Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays… at Belgrade’s Pionir Hall. I’m always here and always there, in Germany or wherever I’m doing a play. I spend half the week there and half the week here. In the neighbourhood where I grew up, ice hockey was more appreciated than any other sport. I also play football sometimes, but I find it kind of tedious. Hockey is closest to my being, to what I do for a living. Hockey taught me to take hits, but also to hit back. Frank once said when explaining why he works with me that I’m good because I’m a hockey player!”

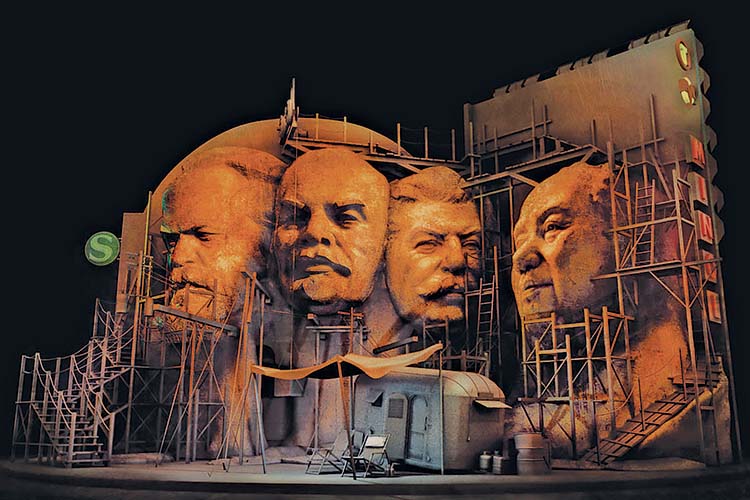

His collaboration with Frank Castorf (71), which has lasted for the past ten years or so, represents a special period and the most successful chapter in Aleksandar’s artistic work. Running in Belgrade throughout this October and November was an exceptional exhibition called Dekada [Decade], held on several levels of the space of the former Balkan cinema, in which our famous set designer presented his wondrous solutions for the plays that he’s worked on with this director. Castorf, who has an old acquaintance with Belgrade thanks to BITEF – the Belgrade International Theatre Festival, is today undoubtedly one of Europe’s greatest theatre directors. He spent a quarter of a century heading Berlin’s Volksbühne Theatre, the People’s Theatre, and during those years he turned it into the world’s best theatre house. Thanks to Denić, his friend and closest collaborator, he accepted an invitation from Jug Radivojević, manager of the Belgrade Drama Theatre, and made his directorial debut in a theatre not located in Western Europe. At the end of October, Belgraders watched the premiere performance of Dante’s Divine Comedy, complete with additional touches from Goethe, Dostoevsky, Peter Handke et al.

Castorf was born and raised in the former East Germany, and when Denić talks about him, he finds numerous similarities between the two of them that are a result of the similar way of life in the former Yugoslavia and East Germany.

There are thousands of sets produced every year in Germany that are in a similar key, technically perfect, but without enough spice. And I, as a cook from the Balkans, like hot and spicy. It seems they like my recipes

“The two of us recognised each other at first glance. We didn’t talk either about art or work, but rather were unified by us both having grown up in a socialist and post-socialist society. He was funny when he said while giving an interview at the beginning of the pandemic: “Well, Angela Merkel isn’t going to teach me to wash my hands. That insults my elementary upbringing”. That’s also how I would have reacted, because we generally react and comment in a similar way, because we had a similar upbringing in the homes and countries we hailed from. We once surprised and regaled the team working on the opera The Ring of the Nibelung. The main character was supposed to disassemble a Kalashnikov while singing. I took it upon myself to show him how to disassemble a Kaleshnikov, and did the work quickly and efficiently. The members of the team, all of them West Germans, were shocked when they saw how adeptly I disassembled the rifle and ask me where I learnt to do it and whether that was in the war? I explained to them that I’d practised it while in the Yugoslav army on the same kind of rifle that was made at Kragujevac’s Zastava factory. Frank laughed and added: “I can also do that with my eyes closed! I was in the same kind of army in East Germany”. The two of us listened to similar music, watched similar films, and lived in similar ways. Perhaps we were slightly more privileged in Yugoslavia, but that was essentially the same life.”

Given his mentioning of The Ring of the Nibelungen, it is worth recalling that Castorf and Denić marked the 200th anniversary of Richard Wagner’s birth at the Bayreuth Festival by creating a fantastic setting of the opus the four operas of the Ring of the Nibelungen cycle. In response to this work, German magazine Das Opernglas, which is considered the bible in the opera world, wrote:

“One massive wooden barn, with a churchlike tower and all the necessary checklist, is on a wisely utilised moving stage with another of the four different sets that set designer Aleksandar Denić created for this Ring and which, in its impressively monumental size, infatuation with details and functional beauty, probably represent the most magnificent thing that has been visible on any German stage in recent times, but without a shred of doubt represent the most sumptuous and appreciated thing in front of which the Bayreuth curtain has raised in the last 30 years. If an Oscar existed for opera scenographers, it would undoubtedly have gone to Denić four times. It is also a powerful demonstration of the strength of the drive of Bayreuth Festival.”

The last play in the Kastorf-Denić settings done prior to the Divine Comedy in Belgrade is Zdeněk Adamec and is being performed at the Burgtheater, while the play’s author is Peter Handke. The Burgtheater, the Austrian national theatre in Vienna, is the second oldest active theatre in Europe (after Paris’s Comédie-Française) and one of the most important theatres in the German-speaking world. The story of the hero of this play, Zdeněk Adamec, is a tragic one. He set himself on fire in Prague in 2003, similar to the self-immolation of fellow Czech Jan Palach in 1969. The play premiered in September 2021. At the very start of the performance, the iconic music of Yugoslav new wave band Šarlo Akrobata’s song Niko kao ja [No One Like Me], resonates with full force for five minutes. And is followed by a tempestuous and very disturbing story that lasts for four hours.

“Jan Palach set himself on fire in protest against the entry of the armed forces of the Warsaw Pact into Czechoslovakia, and at the time he was celebrated by all the representatives of the free world. Adamec set himself ablaze because of capitalism, banks, Coca-Cola, Louis Vuitton, McDonalds… he set himself on fire because of all that shit. Adamec couldn’t handle this system. He expected something better to come after Soviet domination, and instead came the domination of neoliberalism, which is unbearable for a democratically oriented man. Handke understood that tragic fate, just as Castorf and I understand each other when we consider today’s times. We are bound together by our shared post-socialist worldview.”

Everything that once seemed to negate many of the virtues of civil society represented something of a swan song and honey and milk compared to what we’re seeing today

Castorf and Denić’s latest new production – as we discover from our interlocutor – is being prepared in Greece, where Heiner Müller’s MedeaMaterial will be performed next summer in Epidaurus, near Athens. And immediately afterwards they will travel to Hamburg, where they are working on the opera Boris Godunov. He is delighted that the conductor is Kent Nagano, music director of the Hamburg State Opera, who he refers to as a dear friend and one of his favourite conductors.

In his rich career, Aleksandar has been the set designer for 29 feature films by the most successful domestic and international directors and has prepared stages for more than 70 drama performances and operas, while he is also the author of numerous architectural and interior design solutions for dozens of restaurants and cafes.

“Srđan Karanović hired me already during my studies as a set designer for the film A Film With No Name [Za sada bez dobrog naslova]… His choice was more than brave at that juncture, but it turned out that he was right. That was my first set, and thus also the most important.”

He is a recipient of numerous awards for scenography and his contribution to stage design: the Award of German monthly theatre magazine Theater heute for stage designer of the year in Germany, for the play Journey to the End of the Night (Munich’s Residence Theatre, 2014) and for the play Baal (Residence Theatre, 2015); German opera magazine Opernwelt’s award for scenography of the year 2014 for The Ring of the Nibelung (Bayreuth Festival); the Faust Award (Der Faust preis) for the best stage designer of 2014, for the sets of The Ring of the Nibelung (presented by the German Theatre Association (Deutsche Bühnenverein) and the Federal Office and Representation for Culture and Media, in cooperation with the German Academy of Performing Arts and the Cultural Foundation of the German Federal States); the annual award of theatre magazine Die Deutsche Bühne for the 2013/2014 season, in the category of outstanding contributions to the current development of scenography/ costumes/spatial theatrical situation, while he has also been nominated for the International Opera Awards, 2014 and 2022, in the category of designer of the year, as well as for the 2022 Nestroy Theatre Prize. He is also a recipient of all the highest awards in Serbia for the category of the arts in which he works, including the Sterija Award for the stage design for the play Constantine, directed by Jug Radivojević. He served two terms as president of ULUPUDUS, the Applied Artists and Designers Association of Serbia, and is today a professor at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, while he already knows everything that he’ll be doing over the next two years. He also takes 150-200 flights a year.

“I have been doing scenography work for four decades. That is ample time for a man to learn what he can do and his limits. An artist knows best whether he has done something well or poorly. It’s nice when someone compliments your work, but I try not to pay attention to critiques. I saw a critic writing in the title of her text after The Divine Comedy: ‘When will it end?’ Let me ask her such a question: do you want us to reduce Guernica, why should it be such a big picture, it’s stupid? Or to reduce the size of the Diego Rivera painting at Rockefeller Center? Why should he paint in the lobby what he didn’t do in his notebook? That’s the logic of looking at a work of art that individuals consider legitimate and use as the basis to value that work. It mustn’t run for too long, or it mustn’t be large. I always respond to that by saying: anyone who doesn’t like watching a play that lasts five hours shouldn’t come to the theatre or the opera.

The point isn’t where you come from, but rather what you are capable of and ready for. I’ve never been limited in anything by the fact that I’m from Serbia. I did my job, which would get me certain qualifications or accolades, and I would move on

“German theatre aesthetics has its own peculiarities, but I push my own story. I don’t compromise and that obviously has an effect. There are thousands of sets produced every year in Germany that are in a similar key, technically perfect, but without enough spice. And I, as a cook from the Balkans, like hot and spicy. It seems they like my recipes.

Elementary courage is to work and not whinge and thresh empty straw. It is easiest to justify a lack of ideas and quality by blaming a poor financial situation. I would claim that there is always money for a good idea. Every normal producer – whether they’re working on a state, a city or a private production – is benefitted by a good idea, which he will later exploit and pay really well for. Intellectual laziness, the enjoyment of failure, endemic pessimism and excuses like ‘the past hinders the present, and the future is impossible because there’s no money’, have become a formula for the behaviour of the cultural elite and should be called by their real names: cowardice and selfishness. The state of affairs is presented as being worse, there is a forcing of pessimism and apathy, with which new people are discouraged and endlessly certify their own status as undisputed queens and kings of dinosaurs. An important question imposes itself: where are the talented and how ready are they; and what kind of clashes should they throw themselves into or abandon?”

Aleksandar’s success in Germany serves to prove that an artist from Serbia who is great and serious in their work can also work on the biggest theatre productions, which have been produced in Germany over the last few decades. This Serb worked on the most German opera productions at the Bayreuth Festival. But did that bother anyone?

“The point isn’t where you come from, but rather what you are capable of and ready for. I’ve never been limited in anything by the fact that I’m from Serbia. I did my job, which would get me certain qualifications or accolades, and I would move on.

“I’m sorry that here we compare between ourselves without a desire and need to look at what’s happening around the world, what’s being done by some of those that are better, more developed. But this has been our problem throughout history. As a rule, in history, through wars, we have always been on the side of the victors, so we always equated ourselves with those great victors. And we never had time to leaf through the code of civilisation. It seems to me that sometimes, because of our poor behaviour in many situations, we are still in the age before we were conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Our behaviour often manifests as uncivilised.”

I’m sorry that here we compare between ourselves without a desire and need to look at what’s happening around the world, what’s being done by some of those that are better, more developed. But this has been our problem throughout history

For Aleksandar, success is reflected in longevity. He says that the Rolling Stones aren’t the greatest because they play the best music, but because they endure. And that’s why he’s irritated by people who claim that the Rolling Stones always play the same:

“That’s not true! The Rolling Stones always play their own music. Just as I do my own work. Whoever doesn’t like that can listen to and watch something else. The artist has his own personal handwriting style and it is logical that this is recognised about him. I’m not a jukebox that someone can stick a coin in and tell to play something. This doesn’t happen with those who stick to their own writing style. The greatest satisfaction of success that you can do what you love. All that’s needed is for you to also be brave.”

This artist feels sorry that the satisfaction of life has been lost among people; that inclusion has become more important than everything else in the world of the arts.

“You must no longer say that you don’t like women’s football, because you’ll be branded. I don’t like either women’s or men’s football, but I don’t see what the problem is in that.”

Those who loved his film sets, especially in Srđan Dragojević’s We Are Not Angels and The Wounds, miss his big screen solutions that are original and often very humorous. He doesn’t regret turning down film jobs, including an offer to do the set design for one of the sequels to worldwide hit The Bourne Identity. He agreed a long time ago to work with Fatih Akin, one of Germany’s most interesting film directors of Turkish descent. Akin is a great admirer of his masterful work.

After having spent the last ten years on the German theatre and opera scene, or the European scene, Aleksandar wears the halo of a darling of the critics.

“Often in the beginning, depending on the editorial policy of the magazine in question, it would be written in one of them ‘Set designer Aleksandar Denić made a piece of crap, or made something ingenious’, while in another magazine or newspaper it would be written ‘Serb Aleksandar Denić has made a piece of crap or something excellent. That’s how I discovered the editorial policies of those newspapers towards Serbia. If I were to get annoyed by that, I would consider that I actually am a Serb and that fact doesn’t bother me. It just seemed to me that it sometimes bothered them a little. That got lost along the way after a certain amount of time, no one mentions that I’m a Serb anymore, so I end up feeling sorry that they don’t mention it at least sometimes!”