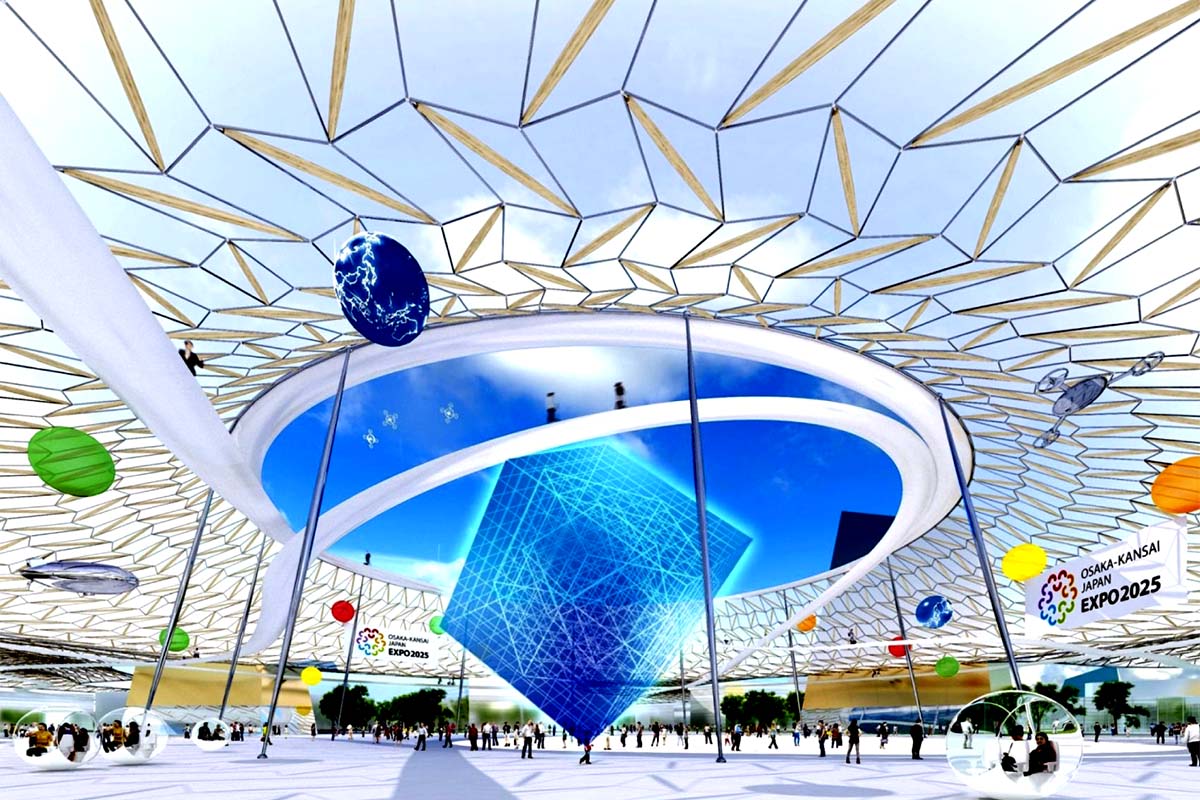

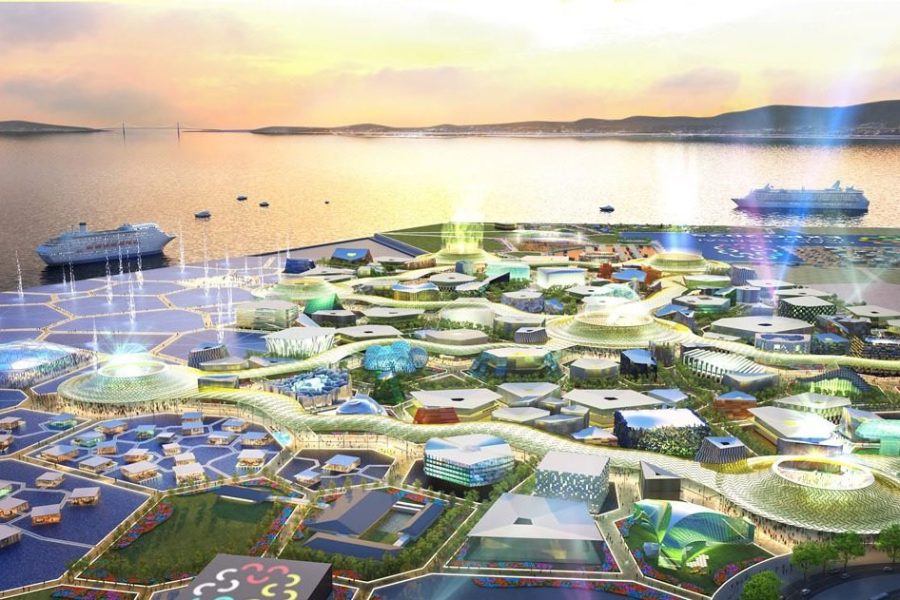

Osaka’s grand plan to “reconnect the world” is gradually taking shape. When completed, huge sections of timber will form an enormous walkway encircling a “forest of tranquillity” and pavilions showcasing the history, culture and technology of more than 130 countries, with the host, Japan, at its heart

The frames – built using traditional methods that don’t require nails – and construction cranes lend a much-needed dimension to the site’s otherwise barren surface of Yumeshima – “Dream Island” in Osaka Bay.

“When people come to the site and see it for themselves, they’re quite relieved by the progress that’s been made,” said Takumi Nagayama, director of maintenance and coordination at the Japan Association for the 2025 World Exposition. “A year ago, there was nothing here, but the ground has been levelled and the land flattened. The basic foundations are done.”

Beginning with the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, world expos have become an opportunity for countries to highlight their history and culture, and demonstrate how they are using social, economic and scientific advances to address the most urgent topics of the times – in Osaka’s case, the quest for sustainable development.

World expos are held every five years and last up to six months. The last one opened in Dubai in October 2021, delayed by the pandemic.

Osaka secured the hosting rights in 2018 – beating Yekaterinburg in Russia and Baku in Azerbaijan.

Guided by the slogan “Designing future society for our lives”, the city is aim to repeat the success of its last expo, in 1970, which drew more than 60 million visitors and confirmed Japan’s transformation from defeated empire into an economic and industrial powerhouse.

Of the 50 or so countries due to construct bespoke “type-A” pavilions, which can cost tens of millions of pounds, only two, South Korea and the Czech Republic, are known to have submitted their designs. Just one has applied to the Osaka municipal government for permission to start building.

With the clock ticking towards the opening officials and politicians are being forced to think again.

Beginning with the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, world expos have become an opportunity for countries to highlight their history

The cost of building the venue is expected to rise from the current ¥185bn to more than ¥200bn (€1.16bn to €1.25bn) due to soaring material and labour costs.

The project is also falling foul of a problem afflicting myriad sectors of the Japanese economy – a chronic labour shortage. The struggle to secure labour will intensify in April, when Japan introduces restrictions on overtime in the construction and other industries.

Some of expo’s problems stem from its offshore location. Access is currently restricted to construction workers via an undersea road tunnel that will eventually be open to the public.

The predictions are 2.8 million visitors during the six-month event, which is expected to generate about ¥2 trillion for the economy.

In August, the prime minister, Fumio Kishida, ordered ministers to redouble efforts to get the event ready on time. ”Preparations for the expo are in an extremely tight spot,” he said.

Full-scale national pavilions could be replaced by cheaper, more unified versions constructed by Osaka companies, according to media reports – an approach that would save time and money, but which would remove the qualities that make the exhibition spaces an expression of each country’s history and culture.

“Preparations are continuing, and we’re working hard to meet the deadline,” said Sachiko Yoshimura, executive director of global communications at the expo association. “We are working on the assumption that the expo will open in 2025 … there is no talk within our organisation of a postponement.”

“Some people have questioned the need for an expo in this day and age,” Yoshimura said. “But we live in a world that has been divided by the Covid- 19 pandemic, climate change and the war in Ukraine. The Osaka expo will be an opportunity for us to reconnect.”