There appears to be nearly as much skepticism of the vaccines that could eventually put an end to the coronavirus pandemic as there is hope that they will.

As the confirmed number of coronavirus cases has exceeded 90 million and the global death toll from COVID-19 has now topped 2 million, there is hope that the widespread availability of vaccines could help bring an end to the coronavirus pandemic. However, in some European countries, there is broad mistrust of vaccines.

According to a number of polls, only 40% of the French population intends to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Opposition politicians and leading medical associations have accused the government of exacerbating the crisis by botching the launch of the vaccination rollout.

As of January 14, just over 318,000 doses had been administered in France, according to Oxford University’s Our World in Data tracker, compared with more than 840,000 in Germany. The government’s initial plan was to vaccinate older people living in care homes and older care staff in January and February. After the plan triggered outrage, the government announced that vaccines would be available to all people older than 75, as well as health and care workers broadly.

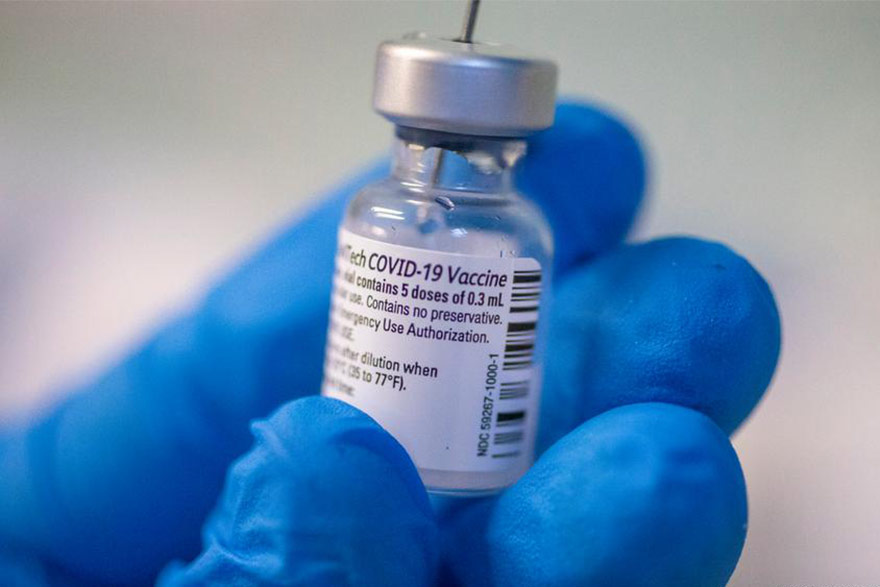

Across the English Channel, with the death rate growing, the British population seems to be less skeptical about the vaccine than people elsewhere in Europe. According to a poll by the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, two-thirds of respondents in Britain intend to receive the vaccine. Some tabloids declared December 8, when the UK government launched its vaccination program, “V-Day.” The first dose administered was the BioNTech-Pfizer jab. However, a number of people have now said they would prefer to wait for the “English vaccine” developed by the University of Oxford and the Swedish-British pharmaceuticals giant AstraZeneca. The UK government approved the vaccine in December; EU regulators have not yet.

Though Italy’s government is on the verge of collapse, a massive vaccination rollout is underway nationwide. By January 14, more than 970,000 doses had been administered, according to Our World in Data — more than in any other EU nation. In December, the government announced planst to open 1,500 vaccination centers, though most of those are not yet in operation. The Milan architect Stefano Boeri has designed mobile vaccination pavilions using ecological materials and decorated with primroses, one of the first flowers to bloom after winter and thus the symbol of a new awakening. Despite a small “NoVax” campaign on social media, most people approve of vaccinations. A poll by the British data and consulting company Kantar released in November, 78% of respondents in Italy said they would “definitely” or “probably” be vaccinated. That was more than in the UK, the US and Germany.

Austrians are reluctant

In Austria, there is growing resistance to vaccinations. According to a survey published in December, only 17% of Austrians “definitely” intend to be vaccinated. The federal government has ruled out compulsory inoculation — an idea floated Markus Söder, the state premier of the neighboring German state of Bavaria. By January 15, just over 84,000 doses had been administered in Austria.

Swedes are broadly skeptical about vaccinations. In 2009, for example, about 5 million people, roughly half of the population, were vaccinated against swine flu, but many children and adults younger than 30 experienced adverse side effects from the Pandemrix jab, developed by the British pharmaceuticals giant GlaxoSmithKline.

About 500 people developed narcolepsy, a long-term neurological disorder that decreases the ability to regulate sleep-wake cycles. Anders Tegnell, who is currently Sweden’s state epidemiologist, was in charge of communicable disease control department at the Public Health Agency in 2009 and oversaw the mass vaccinations. According to a survey published in November by the Stockholm-based research company Novus Group International, 26% of respondents said they did not intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and 28% were undecided.

Spain has recorded more than 2.2 million cases of COVID-19. By comparison, Germany, which has 33 million more inhabitants, has confirmed just over 2 million cases. The high toll in Spain could be one reason why 68% of respondents to a survey published in September by the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology said they intended to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. The Spanish government announced in December that it would set up a register of people who refuse to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Health Minister Salvador Illa said this would not be made accessible to the public or employers, but it might be shared with other government of other EU member states.

The inhabitants of the Central European neighbors the Czech Republic and Slovakia express a similar skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccination. According to a survey published in December by the Slovak Academy of Sciences, about 45% of respondents in both countries do not want to be vaccinated, and roughly one in three do not think that the novel coronavirus is any worse than the flu. Almost 40% of respondents even said they believed that the amount of deaths from COVID-19 has been deliberately exaggerated. The governments of both countries are trying to counteract resistance to the vaccine with high-profile campaigns. Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis was the first person in his country to receive the vaccine in December.

Source: Deutsche Welle, photo: Unsplash