In his testamentary, five-volume book Ephemeris, famous Serbian historian of medieval art, academic and president of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Dejan Medaković (1922-2008), wrote about his ancestors for the first time, extensively and with plenty of evidence and emotion. That was how the public found out about the importance of the Medaković family tree, which over the past two centuries has gifted the Serbian nation many notable contributors to various fields of social action.

Dejan’s great-grandfather Danilo, the secretary of Prince Mihailo Obrenović, contributed to Serbian culture with the printing of the collected works of Dositej Obradović. Danilo’s brother Milorad was the secretary of Montenegrin prince Danilo, and he would significantly shape the character and works of Petar II Petrović Njegoš, as this famous Serbian romantic poet requested that he proofread The Mountain Wreath, his seminal work of epic poetry. Dejan’s grandfather Bogdan was president of the Croatian Parliament and an exile from the house where he was born at 15 Zrinjevac Square in Zagreb, from which he fled on the eve of the fascist Ustasha pogrom of 1941.

Little was known about the Medaković women, whether born or married into this family of Ličans originally from Medak, until Dejan described them in the books of his Ephemeris cycle.

The author of this article had the pleasure and privilege of socialising with this ingenious intellectual for years. On one such occasion, when I was writing about important women of Serbian history, I asked him to tell me about the women who’d had the greatest influence on him, who’d meant the most to him, left a mark on him and made him feel proud…

And here I present his testimony that was given back in 1999.

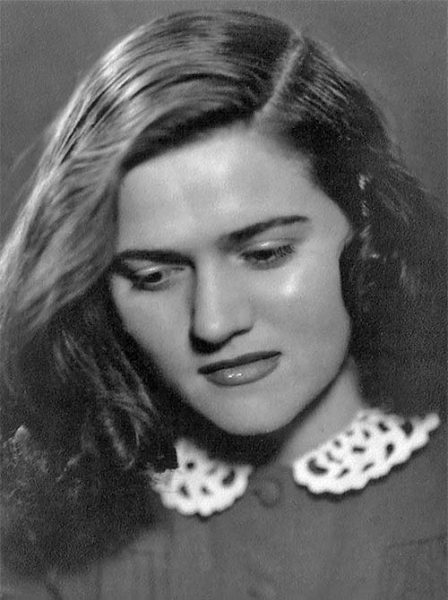

KATARINA MEDAKOVIĆ NÉE MIHAJLOVIĆ

Grandma Katica was my father’s mother, who was married to my grandfather Bogdan Medaković. She played an exceptional role at one point in our family drama. I simply adored her. As strange and unrestrained as she was, she also loved me. The love between her and my grandfather was particularly beautiful. She quite simply adored him. And he her, in his own way. And they were complete opposites. Granddad was very serious, while she was cheerful, whimsical and loved to travel and to buy and gift jewellery. She was stunningly beautiful. I only once saw her let her hair down and that was a magnificent sight. She was an endless source of information for me, not only related to the family, but also to the times in which she lived. Her father was Dr Rista Mihajlović, a public notary, student of Vienna, and the first translator of Heinrich Heine’s poetry into Serbian. He was the son of Justin Mihajlović, a personal friend of Vuk Karadžić, who visited that prominent Vukovar house on two occasions.

Katica’s own grandmother was the sister of composer Kornelije Stanković. She was called Katarina and it was after her that my grandmother was named. Also hailing from the house of Mihajlović was Ruža, whose married surname was Radičević, and she was the mother of poet Branko Radičević.

It’s difficult to fully encapsulate the image of such a strong and forceful woman, a woman who grew up in a house with a piano and books, and who herself had a gift for literature. I remember that the most beautiful experiences of my childhood were linked to her. When she was in a good mood – and she was often very capricious – she would extract a large leather bag containing bundles of letters – from Zmaj Jovina, Laza Kostić etc. At one point, Kostić had been a frequent guest of our house and he took care of my father’s upbringing when he came to Zagreb to work on the translation of the Pandects. Even now I can hear the melodic tone of her voice as she read those letters, selecting them at random as if extracting them from some magical box.

After granddad’s death, my grandma would go at least twice a week to Zagreb’s Mirogoj Cemetery, and I would often accompany her. After visiting granddad’s grave, we would move on, through the cloisters, and she would recount the chronicle of the cemetery to me, as she knew almost everyone who was buried there. Her comments were brilliant, unconventional, ironic, and she didn’t feel obliged to only speak well of the dead. That impressed me.

As someone as generous as she was, following granddad’s death she simply began squandering her wealth and started seriously cutting into the family’s property significantly.

OLGA RAJIĆ

My maternal grandmother, was the unadulterated antithesis of grandma Katica. She didn’t have her cheerfulness, perhaps because she was left a widow at the age of 36. She had a wonderful marriage with my grandfather, who I didn’t know personally and who was also a student of Vienna, a doctor in the Hungarian town of Mohács. There was something in her that was cheerless, melancholic, closed; she was all wrapped up in the emotion that she spent on her children. She had five of them and they all adored her. She was a pianist with an undeniable gift for music, who had already been taking steps towards professional performance before that was interrupted by family obligations.

And for us, the family, she would stage concerts in the house with a large repertoire. She adored Chopin, Beethoven, Brahms etc. And the whole family, including my Olga, were great fans of Wagner. At that time, in one closed circle in Zagreb, Wagner was “a la mode”, so to speak. My uncle, doctor Rajić, brought the first large records of Wagner’s operas from Germany. I had the privilege of winding up the gramophone, and sometimes also falling asleep listening to it, particularly the seemingly never-ending Parsifal. I recall that salon in the Rajić house, which was filled with refined Zagreb gentlemen.

ISIDORA SEKULIĆ

I met her during the time of the occupation of Belgrade, in 1943. I was an assistant, a volunteer at the Knez Pavle Museum (today’s National Museum), and my boss was Kašanin [art historian and curator Milan Kašanin]. I plucked up the courage to visit her one Thursday, because that was the day that she received visitors. I had done an advanced advantage, if I may put it like that, because the Rajić family was well-acquainted with Mrs Sekulić. Namely, as a young girl, Isidora was in the wedding party of the sister of my grandma Olga. I told her that, in an attempt to remind her of my Rajićs, but to my great surprise, she didn’t accept that story. That detail didn’t really overly impress her and she waved it away as though I’d said nothing.

She started heckling me and that made me a little nervous. She asked me who I am, what I am, what studies I’d completed, where I work. When she heard that I was working at the Museum, under Kašanin, she expressed her sympathy for him. She loved him much more than Veljko Petrović, who she considered as being very gifted but vain. “He is a black swan,” she said of Veljko. I was then obsessed with art in general, devouring books, and I’ve never again worked as much as I did back then. At the end of that conversation of ours, she walked with me all the way to the garden fence, which surprised me, and said very dryly “Come again”. That was a sign that I had made at least some sort of an impression on her and after that I came to visit her on Thursdays, which meant a lot to me.

Isidora was a strange combination of phenomenal scholarship, exceptional knowledge, but also behavior that it was tough for me to understand. For instance, she adored Chekhov, like me, was capable of carrying me away in that conversation about literature, and I would experience some sense of ascension because I was listening to such an ingenious and intelligent woman, and then she would all of a sudden, like some tonal change in a piece of music, switch from minor to major and incredibly harshly drop that tone. And, strictly speaking, she would start gossiping, recounting some mundane stories, which genuinely surprised me. I wondered what kind of nightmare was inside that woman.

She was exceptionally gifted in hiding her emotions. She only once mentioned to me her marriage to Emil Stremicki, without any reason, because I wouldn’t have had the courage to ask. She told me, as I recall to this day: “I married out of pity. I knew that he would die after a few months”. I later discovered some ironic and ugly stories about that fictitious marriage, that she invented it and never had it, that it was all her ruse… I was sorry when I heard that, because our world simply loves dragging people through the mud.

Isidora and I parted ways. Considering that time in hindsight, I know that I was mistaken. If nothing else, I didn’t carry myself intelligently at one point and I wronged her. And I did so out of excessive love. And she was simply too vain to accept my harmless candour, which at that time had perhaps come from those lounge parties at 9a Simina Street. It was several years later that we bumped into one another, right in front of the doors of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. She started opening that heavy door, which still isn’t easy to open, and I opened it for her with the greeting: “Good day, madam”. Back then, Isidora already had difficulty seeing, as she suffered from cataracts, but she recognised me by my voice. She asked me how I was doing, which I answered before asking her: “Are your Thursdays still open?” She answered me: “It is for you”. I recounted the conversation to Žika Stojković and he nagged me to return to Senjak. And so, the following Thursday we went to see her, but it was never again the same as it had been before.

VERA MEDAKOVIĆ NEE VELJKOV

I met my future wife at a refugee camp in Belgrade during the German occupation. She was in a state of deep bleaness at the time, because she’d lost the father that she adored. He, as a doctor and reserve medical major, was the commander of the medical train. The Germans hit that train despite it being marked, and he was seriously wounded and died in agony a day later.

That was 6th April, 1941, practically the first day of the war. We also saw each other at her place, at those houses of occupation concerts, as we’d dubbed them. Her parents’ house was at 15 Krunska Street, where her father’s clinic had also been located. When the Allied bombing began during Easter 1944, Vera went to Banat with her mother and sister, to the village of Bavanište, where she’d been born. I visited her there once, under extremely dramatic circumstances. An entire novel could be written about that. There was already love between us, and I only went to see her for one day. And I did so by bicycle. There and back, to the Danube ferry, riding more than 60 kilometres.

We were wed in 1947 and Vera, who was already a pianist, left soon afterwards bound for Paris, for extended specialist studies with Levi, who was a great figure of French pedagogy. She was also in the class of virtuoso Marguerite Long. After being absent for three years, she returned to Belgrade with a diploma, filled with enthusiasm, filled with the wide world. And, as is typical for our situation, these lands didn’t welcome her back in a friendly manner. Her professor, Hajek, was a representative of another school and a split emerged between them. There began trickery, cheating, hiding offers she received, outright conspiracies… I wasn’t in a position to protect her, to help her. Vera was very hurt by everything happening around her, and she surrendered herself to teaching. She ended her career as a full professor at the Academy of Music, always held back from that for which she’d prepared.

ANASTASIJA MEDAKOVIĆ

My 21-year-old granddaughter, opted to study dentistry, to the general surprise of all of us. She is today a third-year student and is extremely satisfied with her choice. She is very subtle, gentle, with all the grace of a girl who practised ballet for many years and completed secondary ballet school. It’s enough for her to hug me a little and I immediately capitulate. I love her unusual beauty, elegance, refined manner. She is a girl with style in these times when impersonality is forced, when individuality is being cancelled and dragged into the crowd. If she inherited something from her ancestors, it might be that special beauty that characterised my grandma Katica.

P.S.

Vera Veljkov Medaković was born in 1923 and died in 2011. Granddaughter Anastasija was named after Dejan Medaković’s mother, who had abandoned Dejan’s father with their five children, which he testifies to painfully in Ephemeris. Anastasija is the daughter of conductor Pavle Medaković, the only child of Dejan and Vera. She has since completed her dental studies and today has a son.