Lisbon has all the ingredients needed to become Europe’s next red-hot art destination: new galleries are opening there, international dealers are setting up outposts, and dozens of artists are flocking there for its affordable housing and studio rents. The city, which boasts a refreshing mix of commercial and non-profit spaces, also has a contemporary art fair, ARCOlisboa

In terms of art, is Lisbon the “New Berlin”, as it has been proclaimed by many articles in the past few years? A promised land for artists from all over the world to come, settle, and live a life devoted to creating art?

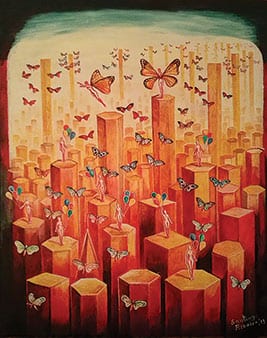

Lisbon offers space and opportunities to start new things. The city’s art scene is open, friendly and unpretentious, while the city feels like an exciting combination of Europe and Latin America.

While some cities seem to be at breaking point and throwing artists out, other cities seem welcoming to them, and Lisbon is currently among the latter. This is a very positive thing, but whether this development remains sustainable in the long run will depend on how solid the projects starting now prove to be. They must keep bringing new elements and maintain a dialogue with the City.

Every so-called ‘New Berlin’ has, unfortunately, suffered from that label, which is a sign of the art world’s constant need to get excited about new locations. Perhaps Lisbon is the new Berlin, but one hopes that it will never be reached by those grey skies.

Besides more favourable weather, picturesque views and abundant sunlight, Lisbon also offers more affordable rents for housing and artists’ studios. While an individual studio in Berlin might set an artist back an average of €400 a month, a similar option in Lisbon has a monthly rent of €200-250, which also helps explain the Portuguese capital’s appeal to young creatives.

The central pillar of the entire Portuguese culture scene (including science, visual arts, dance and music) is the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Founded and funded by an American oil baron who sought refuge in Lisbon in 1942, this now mighty foundation not only maintains the best ensemble of public art collections in the country (in both works of old masters and modern art,) but is instrumental in funding an entire array of artistic events, from small grants for artists to stage their first shows, to the organising and funding of concert series and museum retrospectives.

There is hardly an event in the country that doesn’t include the discreet appearance of the small moniker of the foundation. Until recently, there was also the Institute for Contemporary Arts (EAC), a state funded organisation that provided small grants and organised shows, from 1994 onwards, to support less established artists. Unfortunately, with the recent change in government from Socialist to Social-Democrat, there has been a round of fiscal belt tightening, and the EAC was merged with a larger, pre-existing arts organisation that is widely perceived as short prelude prior to the government’s total withdrawal from the funding of contemporary art.

So, although committed artists enjoy an intimacy and access to modes of institutional support, the centralisation of funding is under threat within the Portuguese model: one threat is the inherent risk of the individual tastes of funding directors becoming proscriptive to the scene at large, while a second is the instability and demoralisation caused when a centralised support mechanism for the entire scene is suddenly removed due to events beyond the art world itself.

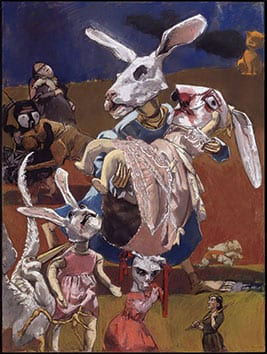

The centre of all things experimental is the art/music/performance space, ZDB, (the name being an arcane homonym/acronym for Joseph Beuys), which runs on young energy alone, having taken the brave step of shunning state funding in favour of artistic freedom. Some smaller Lisbon galleries could be said to exhibit a lack of professionalism at times (irregular hours etc.), as well as the asinine “high seriousness” that accompanies a jangling cash register.

The situation is in transition, however, as new galleries and new money continue to slowly enter the scene. One gallery that has taken an innovative approach is Lisboa Vinte (Lisbon 20). The gallery is located anywhere the artists decide they need to stage their show, after which the gallery director works out the arrangements and technicalities necessary for securing the desired space. This project strives to build upon one of Lisbon’s greatest untapped assets—the city itself. For there are few cities in the world that offer a richer diversity of possible art spaces: from the tangled topology of medieval alleys in Alfama, to the elegant grid system of the waterfront’s post-1755 earthquake reconstruction, from crumbling limestone palaces to brilliant open squares. With an increasingly integrated European economy intent on overcoming geographical divides, it will be interesting to see how the Lisbon scene develops.