He could have been a writer and a painter, but instead he chose to be an actor who writes books that sell in many copies. In his revelation for CorD Magazine, he speaks for the first time about his childhood and upbringing, about the way he has restarted his life from scratch several times – when he came to Belgrade to study in 1978, completed college and started a new life. Then tragedy struck, and he found himself back at the start after being released from prison, and following the NATO bombing he left for New York – where he again found himself having to start from scratch. And that departure was the most painful

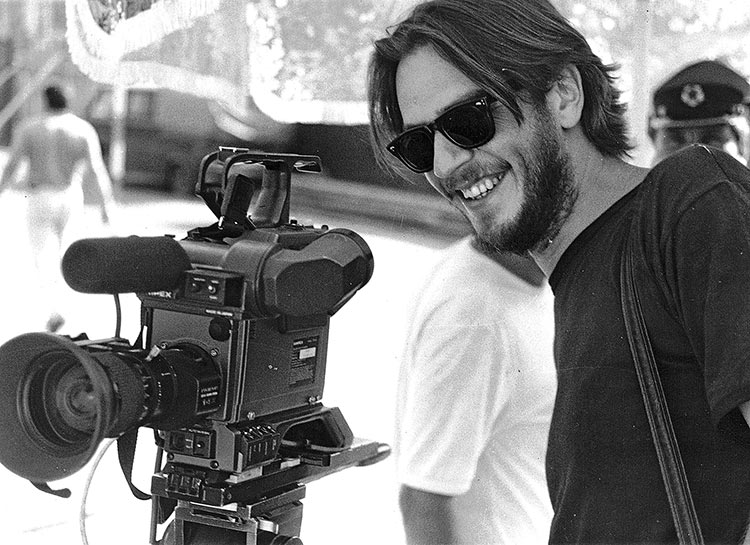

Nothing more powerful and sensitive than actor Žarko Laušević appeared on the film and theatre scene of Yugoslavia during the 1980s. His every performance was worth remembering… and worthy of awards. He was 25 years when he gained huge popularity thanks to the television series Sivi Dom [Grey Home], and he was 27 when he won the 1987 Golden Arena award for the film Oficir s ružom [The Officer with a Rose] at the then Yugoslav Film Festival in Pula and Emperor Constantine in Niš. He was 30 when he was given the Sterija Award in Novi Sad for the characters of Rastko Nemanjić and Saint Sava in the play Saint Sava. He is also the recipient of the most awards at the festivals City Theatre in Budva, Grand Prix at the Film Meetings in Niš, Zoran Radmilović awards etc.

Žarko Laušević (61) was born in Cetinje and was 14 when he moved with his parents and siblings (one brother and one sister) to the then Titograd, today’s Podgorica. His father, Dušan, was a professor of history who went on to become the director of the State Museum of King Nikola in Cetinje. His mother, Roksanda, was a school secretary. The youngest of three children, he recalls a happy childhood and upbringing:

“If there’s anything that I remember with nostalgia from that time, then that would be the serenity of the family fortress. I don’t have the right to generalise, but our parents were dedicated guardians of the treasure of our family love and that implicit tenderness. I was also lucky in life to have great teachers who gave my guidance and showed me the patterns that shape future standards. And I don’t only mean those in the schools that I attended. And nor do mean only the wise people I’ve met.

There are certainly also important books that are teachers, that shift your consciousness, light the path that you’ve intended to take and direction attention towards the signposts at the crossroads that you encounter on that path. Attention to peculiarity. I later searched constantly for that peculiarity in the things around me, and it is – if I may comment on myself – somehow dominant in my handwriting, but also in that which attracts me to acting. Write about the extraordinary… in an ordinary way. As an actor, choose the extreme traits of the character you’re portraying… and be vivacious. Transcribe from life.”

As a primary school pupil, Žarko Laušević was somehow naturally instructed on obligatory school reading. However, his fondest memory from that period was one of his father’s recommendations. That was the book The Most Beautiful Legends of Classical Antiquity by Gustav Schwab (1792-1850). This collection of Greek and Roman stories relates to gods and people, while alongside historical revelations, it also represents a unique moral of good and evil:

“That book remained my obligatory reading for my entire life. I happily return to it even today and one of my children is very strongly attached to that book. That isn’t merely an issue of being familiar with the classics, but rather also something that forms respect… towards tradition, towards history, and ultimately, or initially, towards oneself. That’s how I experience it. Without being familiar with history, we can’t know ourselves.”

In those youthful days, his favourite music was that performed by Miladin Šobić, then a young Montenegrin singer-songwriter who would go on to cause a sensation on the Yugoslav music scene, before mysteriously disappearing from that scene. He had the privilege of listening to him perform in his flat, live!: “I still do so today, though unfortunately only through cassettes, or YouTube. I warmly recommend Miladin. That emotion still hasn’t re-emerged.”

If there’s anything that I remember with nostalgia from that time, then that would be the serenity of the family fortress. I don’t have the right to generalise, but our parents were dedicated guardians of the treasure of our family love and that implicit tenderness

Alongside his victory in the State Recital Competition, at the age of 16 he also became a member of the then newly established amateur theatre company “Dodest” (Dom omladine – drama experimental stage Titograd). That was the first indication that he could become an actor, but also that he could become a writer or a painter, as he is equally talented in those areas:

“I was courageous enough, I am able to say today, to try my hand, because I didn’t fear challenges. I had many complexes, who doesn’t have them? I had constant stage freight and blushed in front of a girl and before a performance. One day I would think that I was skinny, the next day that I was fat. I thought that I didn’t know how to speak, and today I’m still afraid to speak in front of a large number of people.

“I hid my ambitions at that time. I acted in one of the first Montenegrin TV dramas, back in 1978, with Petar Božović and Sonja Jauković, directed by our dear professor, Milo Đukanović, who later became much better known for directing the series Truckers [Kamiondžije], as well as for being a member of the Black Wave [film movement]. My father wanted me to attend the art academy, so he wasn’t really impressed by my acting debut.

However, sometime later he consented and supported me for the rest of his life. My mother and sister, of course, knew about it and supported me, which continued throughout my entire life. Did acting intoxicate me? I don’t know, but it caused me to liberate myself, to find myself and to constantly search further. It’s a great thing when you pick a vocation that will fulfil you for the rest of your life, that you won’t hate and won’t think about retirement. It still fulfils me to this day.”

Žarko Laušević enrolled in the Faculty of Dramatic Arts, in the class of Professor Miroslav Minja Dedić (1921-2015). The class also included Sonja Savić, Zoran Cvijanović, Svetislav Goncić, Branimir Brstina… The professor stayed in contact with all of them until his life ended on 1st March, 2015, the day when Žarko was aboard a plane travelling to Belgrade, where he was set to start work on shooting for the Miroslav Momčilović film A Stinky Fairytale [Smrdljiva bajka]. Today, as always, he chooses words of love and respect to describe him:

It’s a great thing when you pick a vocation that will fulfil you for the rest of your life, that you won’t hate and won’t think about retirement. It still fulfils me to this day

“Professor Dedić was an exceptional personality. We loved and were afraid of him at the same time, but I suppose that’s the very definition of authority. I think he had a decisive influence on all his students. Okay, not to generalise, he did on me. He compelled me to view everything I do through his prism, even today, after his departure. And I will never abandon that.”

Entering the acting ensemble of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre was a great privilege, an honour, and above all recognition for a young actor. Žarko was 22 when he became a permanent member of the most powerful Yugoslav theatre:

“At the beginning of my third year of acting studies, I was invited to the National Theatre by Mrs Vida Ognjenović, where she was the director of Drama and had started directing the play Gorski Vijenac [The Mountain Wreath].

I think the fact that she was also a lecturer at our college had a decisive influence on me receiving Professor Dedić’s consent for that engagement, because the school rule forbade students from working professionally until completion of, if I recall, the sixth semester. It was a small role, but apparently also big enough to ensure that, after the premiere of this most famous work of Njegoš, I was hired by Stevo Žigon for his next play, Romeo and Juliet. Theatre corridors then filled my head with the notion that I had been envisaged as the lead, but Žigon assigned me the role of Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt. I wasn’t disappointed after the casting came out on the bulletin board, but rather decided to do my best. I started almost fanatically practising fencing, while at the same time preparing for an unusual stage element.

Along the way, I directed all my strength to be able, with the incredible physical goal that I’d set for myself, to maintain maximum awareness regarding speaking tasks. Towards the end of the second act, I realised that my months of effort had paid off. After receiving the affections of the audience, despite playing a serious villain, I received applause on the open stage, and at the very end of the first part of the play, there was a unified murmur.

Fear is a common topic in my books. It seems to me today that fear is dominant in this society, and it’s as though I no longer see elementary civic courage

That’s when Tybalt is slain by Romeo’s sword, and my Tybalt – after the directional shock on stage and the extraction of the extras and Romeo himself – stood for a short delay with both hands outstretched, holding a knife in one hand and the fencing foil in the other, fell like a monument being demolished, in one piece, on his back. That was no longer acting. It was fanaticism that I wouldn’t recommend to anyone, in contradiction of any sporting fall, in contradiction of common sense. And in my mind was only the assumption that a man who dies no longer has common sense.

The audience couldn’t believe it. I was rewarded with the most valuable praise for an actor – a long ovation and shouts of ‘bravo!’. If my start had been on those amateur boards at Dodest, back in 1976, I can consider that 1981 and the role of Tybalt as being my true professional beginning.”

That which Professor Dedić had marked in Žarko Laušević’s schooling continued to be done at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, in a much more pragmatic way, by actor and director Stevo Žigon. Laušević today thinks that he couldn’t have had two better mentors during those years that are most critical for a young actor, when his quivering being is still struggling to make the right first step, and every step is on the red line:

“Žigon took me to the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, in his next directorial work. That was Dragan Tomić’s Raskršće [Junction]. It was also a junction for my life. In the mornings, during rehearsals for that play, I was guided by Žigon’s special instinct to uncover the secrets of the professional stage, while in the afternoons I would work on my graduation exam with Professor Dedić, a monodrama based on Njegoš’s The Ray of the Microcosm. When I look back today, that was perhaps the happiest and most fulfilling part of my biography. The system of work that was then formed, together with two great artists, has remained at the essence of my acting to this day. Yes, after Raskršće I received a JDP scholarship and pledged my allegiance to the most splendid theatre in Yugoslavia.”

Žarko Laušević was in his Jesus year [33] when drunken hooligans attacked him and his brother, Branimir, in front of the Epl café-bar in Podgorica, on 31st July 1993. Acting out of self-defence, he killed attackers Dragor Pejović and Radovan Vučinić, and ended up in prison in Spuž (Montenegro), then in the prison in Požarevac. He was initially sentenced to serve 15 years, but that was subsequently reduced to four years, and as Žarko had already served four years and seven months at that time, he was promptly released. He left the country shortly afterwards, moving to New York with his family.

It’s no coincidence that we go to the doctor with a bottle of rakija, whisky, anything to bribe him not to find anything wrong. That is a primordial fear, the fear of disease

And he started all over again: “And I was ready for that, because I’d already started from scratch several times in my life. I started a new life when I came to Belgrade in 1978 to study, and I started a new life when I finished college. Then that tragedy struck, and after being released from prison I was at the beginning again. After the bombing, I went to New York – and started again. That departure was the most painful.

I initially had indications of a possible film career in America, but a new court modification soon arrived that refuted the judgement of the federal institutions and passed a new verdict, which meant that I had to become a completely illegal immigrant, despite having entered the country legally. I realised that a force exists that I could not ultimately defeat. You can prove persistently that this is a cup, while someone claims that it is a pot, a telephone, and you realise that there are no words with which you can prove the obvious truth. Fortunately, that was also settled.”

Life in New York brought many problems and only one advantage: God had rendered him unknown, as a blessing for his drowning in life there. He experienced that which most thinking people on the public scene desire. When fame and popularity strip them of their anonymity, and they had chosen a public job precisely so that would happen, there comes a moment when the strongest desire is to flee from the public:

“That happened to me. New York provided me with the possibility of walking down the street and not being recognised by anyone, although there are plenty of people from our world there. I have that oasis and that peace in that city. I have the joy of hanging out with my children, walking the dog, and any job. And over years I’ve done every job I could – laying parquet flooring, painting and decorating, masonry, removing tiles, installing, all of that fulfilled me because I was helping my wife and children on that elementary path of survival. A man doesn’t only do what he wants, but rather also what he must, when he is confronted by such restrictions. I could otherwise have given up, which I didn’t want to do, because giving up is the easiest thing to do.”

Instead of playing, it was in New York that Žarko started writing. He did what comes naturally to him. He had always kept records of the events and details of his life, so the pathway to a book was clearly marked – diary confessional prose which, at the initiative of Manja Vukotić, then editor-in-chief of Serbian publisher Novosti, he would publish under the title Godina prođe, dan nikad [A Year Passes Quickly, A Day Takes Forever]. The second work is entitled Druga Knjiga [The Second Book], while the third is called Sve prođe, pa i doživotna [Everything Passes, Even A Life Sentence], with both of those works published by Hipatia. That is how Laušević completed his trilogy under the shared title Dnevnik jedne robije [Diary of a Prisoner]. And all three books recorded incredible sales results and are still being sold.

Perhaps the distant future will shed light on history, but art should comment – now. But should wisely pretend to be a fool when facing the past and to imagine that there will never be a new past again. That’s its only chance. And always has been. That protects art from the transience of the moment that it pretends to outwit

Writing in the preface to the third book, writer and director Vida Ognjenović notes:

“Those Laušević’s, precise vivisection of his own position in convicted guilt to the point of cruelty, with authentic sharpness of thought and bold actions in the very heart of the facts, make this book exceptional. Its strength lies in the fact that it is painless, that it doesn’t mystify, doesn’t induce pity and doesn’t pose, but rather exposes and doesn’t recoil when facing confrontation. Due to this completely unique author’s attitude, I believe that this journal book would pass the strictest selection to join the list of the top works in its literary genre.”

Literarily powerful and documentarily convincing, exciting, at times painfully dramatic, Žarko Laušević’s books are rich in the scale of observations that are far from the mere recounting of events. He records the situation in Zabela as prisoner number 28 375, and then meaningfully recalls details from his life before that tragic 31st June, 1993. He explores them and contemplatively rounds them off with a relentless re-examination of everything he participated in:

“Fear is a common topic in my books. It seems to me today that fear is dominant in this society, and it’s as though I no longer see elementary civic courage. There is always a resorting to some detours and roundabout ways to solve basic issues that imply the functioning of the state, chasing a godfather, friend, or someone who you can handover something to finish for you. If the system functioned as it should, there might be no need for any kind of civic courage. I supposed a diagnosis is the beginning of treatment. And we are still afraid to go to the doctor, all out of the fear that they will finding something. It’s no coincidence that we go to the doctor with a bottle of rakija, whisky, anything to bribe him not to find anything wrong. That is a primordial fear, the fear of disease. Two days before going to the doctor, we live textbook lives to reduce the risk of them detecting a disease. And we are sick. I’m just afraid that there’s no council that will convince us of that.”

In recent years, after the film A Stinky Fairytale, which earned him the Grand Prix at the 2016 Niš Film Festival, Žarko Laušević increasingly finds himself in Belgrade. He’s acted in the series Balkan Shadows, Roots, Five, Civil Servant, Name of the People, Alexander of Yugoslavia, The Kalkan Circles, Time of Evil… As a top professional, he turns his roles into unforgettable characters that compel audiences to watch those shows.

And how does he see Serbian cinematography and the rich television production scene now, from up close? What is play that is inherent to him as an actor today, but also play in the society that we all participate in, playing smaller or greater roles:

“Strange times. This is what all incapable people thought during other times. We still don’t know who killed Kennedy … why Ovid disturbed… and why Covid was needed… Perhaps the distant future will shed light on history, but art should comment – now. But should wisely pretend to be a fool when facing the past and to imagine that there will never be a new past again. That’s its only chance. And always has been. That protects art from the transience of the moment that it pretends to outwit.

“Play is a dangerous thing. De ludo ramanorum… panem et circenses… Every society has its games. Sometimes they are Olympic, sometimes who knows what they’re like and who knows who stands behind the need to organise that circus that you are drawn into and think in, convinced that you aren’t part of the game, but rather that you are seriously contributing something, ostensibly changing the destiny of the world. Delusion! I believe only in Andrić’s Aska, as a survival method. The sooner sobriety comes, the less delusion there will be.”