“People in power are always suspicious of artists or people who use their heads to think”

The first role he played was Czar Dušan in Pomilovanje (Pardon) by Desanka Maksimović, as a pupil at Valjevo Gymnasium. His teacher of Serbian language and literature Ljubica Nožica, who led the school drama group, cast him in the role. Several decades later, at a ceremony to present Dobrica’s ring to her erstwhile student, she said that she had already seen that Vojislav Brajović (1949) would be a good actor when he played Czar Dušan.

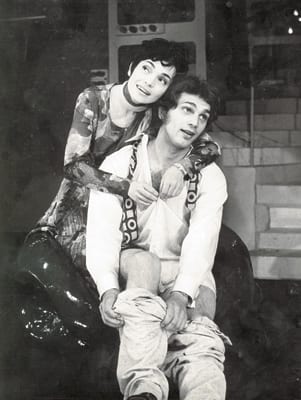

When the Bojan Stupica theatre was opened on 19 December 1969, in the play Kin ili košmar i genije (Kin, or nightmare and genius), Voja Brajović played a servant who spoke only one line: You called, sir! That one line was enough for the critics to recognize him, with just one line he made such an impression that everyone noticed him. After that, he was in the role after role at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (JDP), to which he would remain faithful until today. And when in 1974-75 the TV series Otpisani (Written Off) was broadcast, insane and unforgettable popularity began. Voja was a handsome young communist in occupied Belgrade with the nickname Tihi (Silent), while Dragan Nikolić played a rogue nicknamed Prle, who hated the Germans. Throughout the seventies, boys played Otpisani and were divided into those that wanted to be only Tihi and those that would only be Prle. Voja received hundreds of letters every week from adoring fans throughout Yugoslavia, and when he walked down the street people stopped him for his autograph.

After that, all is history, with over 70 stage and 100 film and TV roles, Dobrica’s ring that was mentioned above, and all of the most important artistic prizes. For three years he was also acting manager of JDP, a candidate for mayor of Belgrade, briefly Minister of Culture, Cultural Adviser to Serbian President Boris Tadić and today in his second term as President of the Association of Dramatic Artists of Serbia. (UDUS)

For three years he was also acting manager of JDP, a candidate for mayor of Belgrade, briefly Minister of Culture, Cultural Adviser to Serbian President Boris Tadić and today in his second term as President of the Association of Dramatic Artists of Serbia (UDUS)

When a great and popular actor accepts that kind of engagement when asked, it can be an advantage but also misuse. It is possible that those who proposed him for the position thought that his acting popularity would help some of their ideas and projects succeed:

“I fought against abuse in all the ways I could, which I don’t think I have to prove. Why was I Minister of Culture? Well, because I wanted to deal with some state issues for the sake of society. I didn’t deal with politics in the narrow sense of the word, but politics deals with us. It’s not impossible that someone thought I was a suitable person to use to push some idea, though of course, I would not like it to have been like that. However, I cancelled that potential attitude towards me through a number of major roles with the best directors of the former Yugoslavia. I was fortunate and privileged to play my best parts with the greatest directors such as Dejan Mijač, Slobodan Unkovski, Jagoš Marković, Egon Savin, Paolo Mađeli…”

Still, as the President of UDUS, he is qualified to name the greatest problem when it comes to the position or status of a dramatic artist in Serbia today:

“The problem is that we don’t have a value system. Ever since I was hired by JDP I realised that an artist’s position was very bad. We can especially witness that today, under an influx of programmes of the lowest possible quality, and here I mean reality shows.

The actor’s place in such a system becomes more and more insignificant, and the state must figure out its role in all this. It should nurture culture, take care of it, defend the arts and national identity because this is how you defend the state. Our profession defends our language, our cultural heritage, and the Association of Dramatic Artists is the one that should stand up for the profession, but it should also defend cultural institutions, without which there are no new and good cultural values.”

He says that he was privileged to be Minister of Culture, but what he learned in that period is very interesting:

“In the short time I was Minister of Culture, I realised just how much there exists a non-objective, incorrect, irregular, unjustified fear of culture. People in power are always suspicious of artists or people who use their heads to think, imagining that this can be a barrier to what they do, or that it makes them inferior or incompetent. Creativity is needed in every profession, and when someone has proved himself as a creative person, instantly there is envy and we show that bad habit of ours that we simply do not forgive anyone their success. While I was the minister, I tried to surround myself with professional and dedicated people who knew their job, who knew more than me, and we started the huge task of drafting an umbrella law on culture.“

CorD’s interviewee explains that one of our biggest flaws is the lack of continuity in work and our constant need to change things at any cost. That is very harmful to the development of society:

“The problem is that we don’t have a value system. Ever since I was hired by JDP I realised that an artist’s position was very bad. We can especially witness that today, under an influx of programmes of the lowest possible quality, and here I mean reality shows

“This leads to a number of sycophantic visions for the development of culture and society in general, and unrealistic views. This cost us from 1945 to the 1990s, and now the policy of sycophantic single-mindedness appears once again.”

As a former minister of culture how understanding is (isn’t) he of what the Ministry of Culture and Information is doing today, and the minister himself? Voja Brajović replies:

“To answer this question I have to go back to my childhood when Tito already said a historical NO to Stalin. Yugoslavia was already close to a banana republic. Someone from the political establishment and there was some thinking people there, figured out that the country could be promoted through culture. And that was how a great exhibition of Yugoslav mediaeval art happened at the Chaillot Palace in Paris, plays by American playwrights such as Tennessee Williams were performed in Belgrade, Bitef and Fest were founded… Not to mention Mediala in the fine arts, the black wave in Yugoslav film, and other accomplishments that spoke of a powerful breakthrough of culture in that country.

“Today, in this small country of ours, whose borders we still don’t know, it must be known that we have so many talented individuals and they present a true weapon of this country, this society. And they must not be impeded. The importance of art and creativity must not be marginalised. It would be disastrous to reaffirm trash and kitsch like in the recent past, and we can see that those stupid and awful games are being played. It is not a coincidence that in the biggest systems, ministers of culture were the most important people. Here, and in the rest of the region, it is not taken seriously. The government acts like a football coach when he doesn’t know where to place his player he says to him – go and be a defender! In other words, go and be a minister of culture!”

Voja can’t remain silent before the fact that the government does not understand the importance of investing in culture, science and education. The order of these three areas is not relevant, but it is important to know that all three are vital for social progress, for raising a level of civilisation:

“We began to lose awareness of this a long time ago, and I would say that in the last twenty years this has been done on purpose, to manipulate people more easily. In all these years as an actor, a member of various city cultural forums, my main goal has been – how to put an artist in the right place to contribute the most to his community and society as a whole.”

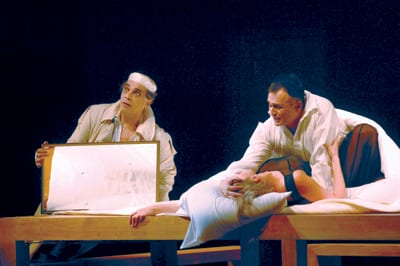

Voja is lucky to complain about how much work he gets. He can brag about being very busy performing, shooting. He stars in a TV show Sinđelići, in six plays at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, in Atelje 212, and especially important is his play Voz (Train), which he directed in Zvezdara Theatre, co-starring Sergej Trifunović. It is a play based on the work of Cormac McCarthy, and it has been touring the region with great success:

“I feel fortunate because I can choose what I want to do. The reason why a play is set on stage is crucial. Many young directors reach for effects, and I am interested in what message that play sends with its story, it is important that it makes me think, gives me goosebumps. I am happy that there are young people who do theatre and think with their own heads and want to say something to their fellow man.

“The reason to stage Voz and star in it was above and beyond political developments. I want the spectator to get a new perspective on his surroundings and the meaning of life. All this time since we have been playing Voz I didn’t meet anyone who was indifferent towards it. Its greatest quality is that it affects the audience even after it ends. This play almost nullifies any political topic.”

There was an extraordinary event involving this play. Dragan Nikolić, when he was already gravely ill and a few months before he died, together with his wife Milena Dravić and friend and fellow actor Žarko Laušević, watched from his bed in his apartment a major part of the play, performed for him by his kum Voja (Dragan Nikolić was the best man when Milica Mihajlović and Voja Brajović were married in the monastery of Dečani) and Sergej.

It is hard to separate Brajović’s private and professional life from his political struggle which he began back in the 1990s. We recall his act from December 1999 when during the play Bure baruta (Cabaret Balkan) in the National Theatre (JDP burned down and was being rebuilt) he demonstrated a T-shirt saying Otpor (Resistance), with its well-known clenched fist symbol, and raised his fist. This was welcomed with 15-minute thunderous applause.

In the short time I was Minister of Culture, I realised just how much there exists a non-objective, incorrect, irregular, unjustified fear of culture. People in power are always suspicious of artists or people who use their heads to think

“After that, Željko Simić, the theatre manager and Minister of Culture at the time, said that that kind of striptease would never again happen in the theatre and punished us by banning us from the National Theatre. It was well known that I was against the people on the political stage in the 1990s in Serbia, that I strongly opposed the civil war in the former Yugoslavia, and that I could be a nuisance to the authorities. They kept a close eye on me so that I would not inspire things that were not to the government’s liking. Of course, some people hold it against me that I caused trouble for my colleagues but that was an engaged play with a symbolic finish, and I believe I acted in accordance with that symbol.”

It is a less known fact that Voja Brajović was six months old when his father, a high JNA officer, was imprisoned. His mother took care of him and his older brother. It is easy to assume that Vukota Brajović was eliminated ‘according to IB’, as they said in those days, meaning that he violated the infamous Informbiro resolution that marked the split with the USSR:

“My father was no enemy, and my mother couldn’t accept his arrest. The thought of giving him up was out of the question. For a year she didn’t know where he was and with her two children, she went to see everyone just to find out where her husband was. She was in Marshall’s headquarters as well. And then after a year and a half, she reached Gradiška where she finally found him doing time. There was a man at the graveyard who took us in. My mother cooked green peas and put a baby’s dummy in it so my father would know that it was from her, that she was there. The guards were cruel to prisoners and they used the most horrible methods to destroy them. One time they told my father that his wife and eldest son were drowned in the Zeta River, and our house in Montenegro was near the Zeta river. He jumped and started yelling: You are worse than the SS, you fascists! They beat him so hard that he could not stand up for days.”

Voja grew up in Valjevo, his mother’s home town, and they still call him Vojkan over there. He says that it is hardest for him to perform there:

“I have the biggest jitters when I perform in Valjevo. It is not easy for my friends over there either. I don’t want to let them down and they worry I will get something wrong.”

He named his first-born child Vukota, after his father, and from his first marriage he also has a daughter Iskra. From his second marriage with actress Milica Mihajlović, he has a son, Relja. He recently became a grandfather, his daughter Iskra gave him a granddaughter.

He thought he would study sculpture because that was his first artistic love, but he enrolled in drama school with professor Predrag Bajčetić and graduated with professor Ognjenka Milićević. As a young and handsome actor, he performed in the oldest play of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre Buba u uhu (A Flea in Her Ear). He is grateful to director Dejan Mijač who at the crucial moment of his career gave him a part that destroyed his beauty and allowed him to become a character and further on a sovereign master in JDP. For his acting achievements, he won all the important awards – from Sterija’s to Ljubiša Jovanović, October Prize of Belgrade, Ćuran at Days of comedy in Jagodina…

He was a young member of JDP when he was accepted in the Communist Party. It is an interesting story of how he became a communist:

“After the famous Tito speech in the wake of the 1968 student protests, a party secretary at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts gathered us and told us that we behaved well during the protest. He suggested that youth, intelligentsia join the Communist Party. I stood up and told him: I can’t be a member of the Communist Party because I’m your opposition. He was prepared and told me that the Party needed exactly that kind of people. I replied we don’t need your kind and that was it. They never invited me again. Years later, when I became acting manager of JDP my friends told me: Listen, you’ll be manager tomorrow and you have to be in the Party or they could make a lot of trouble for us. And that was the reason why I joined the Party. Although, regardless of political affiliation, I believe there are democratic and non-democratic people. As a kid in high school I thought that a communist was someone who was the best, most honest and that if you didn’t have it in you, you couldn’t be a communist. Maybe I got that from my father, I don’t know.”

“I have the biggest jitters when I perform in Valjevo. It is not easy for my friends over there either. I don’t want to let them down and they worry I will get something wrong.”

His upbringing was leftist and he got it from his family, his Montenegrin father and Valjevo mother:

“My parents fought in the war, my mother went in 1944 after Valjevo was liberated, but she still took part in fighting for freedom. My father was a young communist, a member of SKOJ before the war, a rebel and anarchist who decided to fight and eventually he won. I got this fighting spirit from him.”

Voja is remembered for his partisan activism, first in the Communist Party where he was one of the first advocates of a multi-partisan system. Later he was an active supporter of the Democratic Party. As a champion of brotherhood and unity in its original form, he took the breakup of Yugoslavia very hard:

“Yugoslavia was like a family to me. Just as I was loved in my family, I was loved in that country too. I considered myself a Yugoslav, a federalist. I believed that I was a welcomed guest in Maribor, Rijeka, Zenica, that my hosts were accessible, that I could visit them whenever I wanted, that I would not have any trouble wherever I went. Maybe that was utopia, but that country guaranteed that. First and foremost I was looking forward to all that space. As a kid I spent summers in Kupare, Igalo, Opatija, later in Hvar, we performed there. I was 15 when we visited a village without a hotel so we stayed with the locals, in their homes. I will never forget those huge feather covers we slept in. After the show, our hostess would wait for us with the most amazing food. I was aware that this was the Ustasha region, that long ago members of my people were persecuted there, but I always thought that life could get better, that people could come to their senses. I still believe that people can be better and I try to see the best in every human.”