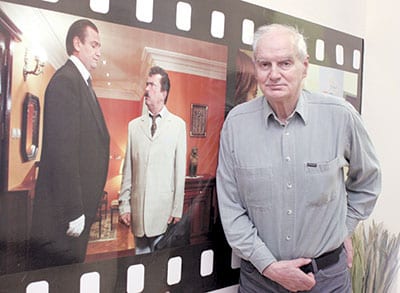

In the 60-year history of Yugoslav and Serbian television, almost half a century belongs to Siniša Pavić. He has authored some of the most watched, most popular and most repreated television series: Graduates, Hot Wind, Better Life, Happy People, Family Treasures, Here Come the Dollars, The White Ship, Theatre in the House…

He is the author of the book Višnja on Tašmajdan, which was adapted to film, and was the screenwriter of several feature films with historical themes, as well as documentary dramas with topics from recent history.

Siniša Pavić (84) has created numerous characters that are loved and remembered by the public, but one special and unique character is definitely Šojić from the series White Ship, who has become the image of a corrupt Serbian politician in the last few decades. Politics as a mockery became the main theme of this series because politics has also become the greatest abomination in our lives:

“I belong to a generation that believed in a lot of things. We believed in Yugoslavia, in the freedom that somebody would bring us, in Tito, in socialism, in self-management… After the collapse of Yugoslavia, we believed that Slobodan Milošević would do something for Serbia, after 5th October we believed in the new government, in democracy. In human freedoms and rights… Something of the things we believed in even came to pass. What has gone backwards lately is the quality of life and relationships among people. We have reached the point where no man believes anymore in what he is told as a political project, as some kind of vision. A man no longer trusts another man; we no longer trust each other. There has been so much assimilation of so-called deceptions, swindles, empty rhetoric, false promises etc., that ordinary people don’t believe anyone anymore. They vote for those people they see on television, but they don’t trust them. This is our paradox.

“And someone voted for that Šojić [character from the TV series White Ship] because he wouldn’t be able to enter parliament if someone didn’t vote for him. This Šojic is vulgar, uneducated, cunning, one could say underhand, very selfish, and very grateful for the creation of a situation in which human stupidity and greed fuse with normality. That’s because even though Šojić seems abnormal, he actually produces the new normality.

The White Ship series is a place where elites and scum meet. And the scum takes over the helm from the elite. That’s a sorrowful realisation, and I’m interested in whether the people who watch White Ship just laugh, or recognise the essence. For me, the story of a mass auditorium is a hollow one, because I don’t think everything can be equated. You cannot equate yourself to someone who has not read a single book in their life. There is no common denominator there. I wouldn’t be able to write for all types of viewers. This Šojić has characteristics common to all of us: we all want to lie a little, to put down, to deceive, and that’a quite understandable to the viewer.”

Siniša Pavić’s father, Ante, was a Sinjanin, a Croat, but in terms of his ideas and affiliations, he was a Yugoslav. He gave one of his sons a Serbian name, Siniša, and the other a Croatian name, Damir. Known as a righteous, honest and committed Yugoslav, in the years just prior to World War II he realised that he could not survive in Croatia. Siniša was five years old when the Pavić family moved to Belgrade in 1938. The father died in 1967 and remained a Yugoslav until his death:

“I often return to memories of my father, to whom I owe absolutely everything. From a happy and carefree childhood during the worst period of history to those personal qualities that he managed to transfer to me. Today, it is clear to me that he still led a war, a war without bullets, but equally tough and honourable. I wish that he could know, hear, that he won it. There are, however, no human qualities and values that life doesn’t bite on and ulcerate. And that’s why it’s necessary to go back, as often as possible, to those first pages as sources of strength and an always solid foothold.”

We have reached the point where no man believes anymore in what he is told as a political project, as some kind of vision. A man no longer trusts another man; we no longer trust each other. There has been so mush assimilation of so-called deceptions, swindles, empty rhetoric, false promises etc., that ordinary people don’t believe anyone anymore

Vlasotince is a small town in the south of Serbia that’s home to 18,000 inhabitants and of which Siniša is an honorary citizen. It was in this town that one of his most popular television series, Hot Wind, was shot, in which Ljubiša Samardžić shone and earned the nickname Šurda, after the hero he portrayed. Also shining in that series was the young, gorgeous Vesna Čipčić. Pavić’s wife and associate on the script, Ljiljana, was born in this town, and the two of them have long since built a new house where they live there, ever rarely coming to Belgrade. Siniša buys all the daily newspapers every day, reviews everything, and reads what interests him:

“I have all the sources and I read all people who are capable of writing. I don’t want to make a selection regarding the newspapers I read, rather I make a selection regarding the information I receive. I also like watching TV, albeit selectively. Whenever some of my series are repeated, I watch because I want to see how that looks to me now, whether I have a different attitude towards that now in relation to the one I had yesterday. I have a living relationship with my work.”

It was with great pleasure that Siniša watched all four episodes of Oliver Stone’s conversations with Russian President Putin, broadcast locally on RTS recently:

“I really liked Oliver Stone’s approach. Simple, without excessive officiality. I got the impression that the two of them simply chatted. I watched the body language, the expression on the face of Russian President Putin, I liked his remarks and his polite cynicism, just as I unmistakably saw when he avoided answering direct questions. Stone is an intellectual who knows a lot and is well capable of understanding. I think that such interviews actually represent a massive undertaking. I especially like watching English BBC series and am currently occupied by Downton Abbey. I have asked for it to be burned for me so I can watch it all at once.”

Throughout his working life, Siniša was a judge, and it was as a judge that he retired. Many were ready to explain that his selection of characters from the people was actually the result of his many years socialising with lawmakers who came to court with the most varied demands – ridiculous, bizarre, sad. In one critique there was always consensus, and that is that Siniša loved those characters, those people from the nation who was so well received among viewers. Although it was almost obligatory during the time of Socialist Yugoslavia for judges to be members of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, Siniša was not one, though his beliefs were always leftist. He went to work every day and would write in the afternoons and evenings. He never had a study room, nor even a desk. He wrote exclusively by hand. He produced more than 80,000 handwritten pages. He submitted those manuscripts for typing and was always able to find a person who could read his handwriting:

“I don’t have my own workplace, I do not have my own writing desk. I never had that and I think it would bother me. I couldn’t work differently to writing on a piece of paper on my knee. That position suits me. I can stop writing, look upwards and think, I can listen to what others are talking about and simultaneously think about the text. That’s an unusual way of working. Everyone’s astonished that I am able to write in a crowd, in a waiting room, to record something while waiting for the amber and green lights at the traffic lights. It happened that I had little time to write in my life.

Throughout his working life Siniša was a judge, and it was as a judge that he retired. Many were ready to explain that his selection of characters from the people was actually the result of his many years socialising with lawmakers who came to court with the most varied demands – ridiculous, bizarre, sad

I worked as a judge for seven hours, drove my wife to work and returned home from work, and we lived a long way away – all of that restricted me and so I had work when I had the time, and I sometimes had it in very bizarre situations. I’m not bragging about it. It’s simply how it was. If I’d waited for the conditions I have today, I would never have written anything. And when we say conditions, we are actually thinking of situations in which we are spared from great problems. I resolved them together with my wife. Nobody spared us, nobody gave us anything in life, nothing fell from the sky, and I think that’s good.

I used to write very fast, but with the years that progress increasingly slower. I’m constantly changing something, rewriting, adding… Actually, a person changes. For example, I read War & Peace for the first time in high school, at the age of 18. Then I read it ten years later, and I wasn’t aware of everything I had picked up from that book. In fact, 50 per cent of everything I know about the world and people, I know from that book. The third time I read War & Peace was when I was over 40. Then I reread my other favourite writer, Gogol. Gogol always attracted a character rich in qualities. I was always interested in that man with qualities and never interested in a man without qualities. I first come up with the character and then create the story. If he has a good character, then he starts leading me.”

One of the greatest Serbian actors, Milan ‘Lane’ Gutović, achieved enormous popularity playing Srećko Šojić in the series White Ship. Known as an outstanding improviser, he says that he didn’t need to improvise for this character because Pavić’s lines were “clear, precise and accurate even without my intervention. The humorous edge of his texts is precise and focused on the right place, so it sometimes seems that the text is actually satirical, although I know it’s not. Sometimes it seems that reality lags behind events Mr Pavić has already written.”

In the series Hot Wind, Here Come the Dollars, Family Treasures etc., Pavić wrote a lot about people who believed in a better life. As the years passed, it seemed that the writer also started believing less in a better life:

“I can write a series that will be entertaining, like the previous ones, and in the end, everyone will go to the seaside, where the people will love each other and eventually have gentle feelings, or positive emotions, as they say now. But if you have talent, and I believe that I have, you have to say something that most irritates people at this moment. And people are currently most irritated by the political situation. And social, because they’re connected. We are a society in which you have one layer of people who run the country, and an enormous number of people waiting to see what will happen to them. I don’t think people are divided, nor that the one who isn’t in power is good while the one in power is bad. I that we’ve all, in essence, lost some human values. The fact that we have lost them as people, as voters, as thinking beings, allows those who aren’t good to move up.

“That negative selection is not a consequence of some party dictatorship that could be explained at the time of Tito when he chose those committed to the regime and the party, rather now that is something that comes from us.”

I was always interested in that man with qualities and never interested in a man without qualities. I first come up with rhe character and then create the story. If he has a good character, then he starts leading me

CorD’s interlocutor insists that he never received anything from the state, that he didn’t even want to use the privileges he could have had he accepted to become a member of the Association of Serbian Writers. He could live a decent life with his family from the money he earned, and at the time of the bombing in 1999, in the cellar of his house in Vlasotince, the shelter was found by 18 people, mostly mothers with children whose husbands were in the army. Whenever required, he helps or organises assistance in Vlasotince, and he’s happy to live in an environment of modest people who have long considered him their own. That’s because he was left without his homeland as a child, was left without a mother early on, and when Ljiljana first brought him to Vlasotince to present him to her parents, he fell in love with the area. And accepted it as his new homeland. Many characters from his series are actually from here, from this tranquil town on the banks of the River Vlasina, where Siniša feels the best.

Asked what worries and irritates him on the global front, he says he is truly struck the disappearance of the value system:

“We are today exposed to the styles and dictatorship of money. And that’s money that doesn’t exist. Because if there was money, you would find a way in that system dictated by money, in addition to kitsch and crap, to also finance the creation of something worthwhile. In rich societies where there is money, alongside mediocre creations, there are always capital and valuable artworks. And here? I’m afraid we will soon have only a system of crap. That the only things financed will be that which the market verifies quickly and immediately, and that no one will be interested any longer in insisting on creative patience, nor enduring values.

“However, I believe that a real artist will prove victorious in every situation. The only question is whether you will stimulate the artist in that effort or discourage him. You cannot rely solely on geniuses who will sacrifice everything to create their work. You must socially stimulate people to create.

“In our nation, there is one saying that relates to today’s times, and it says – look at what you live from. It is especially common among young people and means – look at what can benefit you right now. And that then means there’s nobody to kick start this country. It’s like we’re all directed towards people forming when little, and not as people of format.”

No matter how much the characters in his series dealt with politics, Siniša personally never had even the slightest emotional relationship towards politics. He is, as he attributes to his hero Šojić, an emotional observer:

“I had four offers for four very high political functions, and I declined all four. That’s not a job that suits my moral being. I can’t claim that I’m always right, nor that I’m the most capable of everything, I wouldn’t be able to constantly praise myself before the people. That’a job that pushes a man into banality, and what I do is an attempt to get us out of banality, for us to rise above everyday trifles and trivialities.

In rich societies where there is money, alongside mediocre creations there are always capital and valuable artworks. And here? I’m afraid we will soon have only a system of crap

“Unfortunately, today you have a situation whereby if you are not politically correct you are almost unable to find work. In fact, you can do whatever you want, but access to the money that enables the creation of artworks is more difficult for those who are not close to the current political establishment. That’s why there are so many artists today who allow themselves to be close to the government, to engage politically, to place themselves alongside some political option, agitating at pre-election rallies, and then afterwards collect on that, getting jobs and having commissions approve their projects. No political option will tell you that you cannot create, but there is a way to conduct that.”

Pavić has worked a lot throughout his entire life, and it is only in recent years that he has discovered the attraction of occasional idleness:

“There are days when I’m idle. Once actress Marina Vladi, who was married to famous Russian actor, writer and musician Vladimir Vysotsky, said that she most loves being idle with a guitar. And she added: Don’t underestimate idleness, without which there would be no Dostoevsky. That sentence makes sense because only people who have plenty of free time can observe the world and say something about it.”

And when asked whether he believes in the longevity of his works, given that some of his series, which are two or three decades old, are still repeated on television today with great success, Siniša responds:

“I care about my work standing the test of time. So far it has, but what will happen in the future is not mine to judge. Though I’m not sure that a writer like me will even be needed by the television of tomorrow. ”