During a visit to Belgrade during the 1990s, Richard Holbrooke, a U.S. diplomat and one of the authors of the Dayton Agreement that ended the war in Bosnia, accused Slobodan Milošević of stifling media freedom in Serbia.

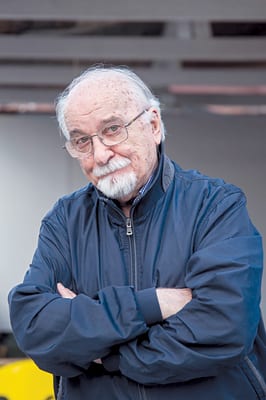

What this famous cartoonist did to the former strongman remained as testimony to a period of time in 3,700 caricatures, which is how many Corax published during the period of Milošević’s rule. Of course, he also continued sketching images of public figures, primarily those from the political scene of Serbia, and he’s still doing that today.

Every day his cartoons appear in daily newspaper Danas because this artist cannot imagine a day without a new contribution:

“When I read some news story, I immediately consider how I could comment on that. I’d call that an occupational deformity that implies that I must react. Something similar is done by a journalist when they decide to write something. I think in pictures and use pictures to describe my ideas and thoughts. I have always said that this caricature with which I react to reality can be a slap in the face, but not an insult. It must be ironic, to have a sting, but it mustn’t humiliate anyone.

While I work, I think of the so-called little guy who’s going to look at it and who should be able to recognise everything and feel good, even superior compared to those who I draw and who, unfortunately, decide our fate.”Predrag Koraksić is known to the world as Corax, and to his friends as Goga. His Koraksićs are originally Greeks, while the hamlet of Koraksić is near Čačak.

His father Stojan was a teacher, communist and revolutionary, who was accepted into the Party in post-war Yugoslavia by politician and Chairman of the Collective Presidency of Yugoslavia Cvijetin Mijatović aka Majo. Stojan was in Bosnia, in the village of Liješan above Zvornik, he met a young teacher called Zora, or Zorka, who he brought to his native Gornja Gorevnica, nine kilometres from Čačak. Zora gave birth to their son, Predrag, in 1933.

His father Stojan was a teacher, communist and revolutionary, who was accepted into the Party in post-war Yugoslavia by politician and Chairman of the Collective Presidency of Yugoslavia Cvijetin Mijatović aka Majo. Stojan was in Bosnia, in the village of Liješan above Zvornik, he met a young teacher called Zora, or Zorka, who he brought to his native Gornja Gorevnica, nine kilometres from Čačak. Zora gave birth to their son, Predrag, in 1933.

“Although I am a Serb, I was raised and brought up in the spirit of Yugoslavia. My mother was a Bosnian from Fojnica, her father was from Split, my great-grandmother on my mother’s side was Italian and my father was a Serb. My father’s entire family were partisans, while mother was a member of the anti-fascist movement.

At the beginning of the war, my father was arrested by the Krauts and transported to Germany. He leapt from the train somewhere in Slovenia, escaped and returned to the Čačak area. He was the best friend of national hero Ratko Mitrović. On that famous picture kept in the National Museum of the liberation struggle, where Ratko Mitrović is speaking at a rally in Čačak, which was then liberated, my father is pictured standing in a Partisan uniform. That was the last picture of him.”

Stojan Koraksić was captured by the Yugoslav royalists, the Chetniks, and taken to Ravna Gora, to the headquarters of Draža Mihajlović. They cut off his fingers and shot him, but he somehow miraculously survived that shooting and managed to crawl, seriously wounded, to a stream where housewives from the village collected water. One woman from a Chetnik family saw him and told her husband, so more Chetniks came and finished him off. Predrag and his brother, who was four years younger, didn’t know that their father had been so brutally murdered. The children waited for him to return from the war and only discovered the truth after the war:

“When that happened with my father, my mother, my younger brother and I were practically condemned to death by the Chetniks. One villager who was a servant at the Chetnik headquarters told us that some black threesome was supposed to come to slaughter us, so we fled immediately.

First, we went to Čačak, to stay with some of our godparents, then we caught the train to Belgrade. My brother and I were escorted on the train by a girl from that god-family who generally smuggled milk curd and cheese into Belgrade and sold them. My mother was smuggled in illegally from Zemun on some rowing boat, then went to her parents at Gunduliceva Street 28a. And my brother and I were at Aunt Duda’s on Slavija, who managed to get some ausweis (ID card/ pass) and transfer my brother and me to Zemun, which was then Croatian territory. There we lived under my mother’s maiden name and I was called Franjo Božić.”

I have a principle of no longer working for anyone who refuses to publish one of my caricatures. At Vreme that happened when Dragoljub Žarković requested that I stop drawing Vojislav Koštunica, as would also happen many years later to Duško Petričić at Politika, when the editor in chief didn’t want him to draw Aleksandar Vučić

It was only after the war that Predrag learned from his uncle, General Velimir Terzić when and how his father was killed. His mother was silent about that for a long time. The war years were painful. Mother was arrested and the children were starving more than full. Predrag finished secondary school and made a compromise with his mother that he wouldn’t be an engineer, according to her wish, nor an artist, according to his, and instead enrolled in architecture studies.

“I was 17 when I published my first cartoon in Jež. It was a miracle for that time. The average monthly salary was 3-4 thousand dinars, but for that one caricature, I received 600 dinars! I took my whole team, seven or eight buddies, pals who hung out, to the Zemun cake shop “Kod glumca”. We ate everything they had and they all felt sick. So that was the first fee I received and that’s how I spent it.”

In the last year of high school came sculptor Milan Besarabić, who also did caricatures in the form of sculptures, making small figures of judges, bureaucrats … out of terracotta. They were caricatured figures. He had a studio at the Fairgrounds where his talented students went, and in the school, he made a painting section in the loft of the school, in the attic. Everyone who wanted to learn something about drawing from an artist who wanted to help them came there. Those were Corax’s first drawing lessons.

In the last year of high school came sculptor Milan Besarabić, who also did caricatures in the form of sculptures, making small figures of judges, bureaucrats … out of terracotta. They were caricatured figures. He had a studio at the Fairgrounds where his talented students went, and in the school, he made a painting section in the loft of the school, in the attic. Everyone who wanted to learn something about drawing from an artist who wanted to help them came there. Those were Corax’s first drawing lessons.

After his first caricature, he continued being published in Jež, while in his studies he completed the third year of his architecture degree and then gained employment as a professional cartoonist for the newspaper Rad. He was hired by Ašer Deleon, one of Rad’s editors who was that very year sent to serve as ambassador to the United Nations. Danilo Knežević then arrived as the new editor in chief, and Koraksić spent three years there. When the evening news, Večernje Novosti, was launched, he was invited to join the editorial department by Slobodan Glumac, the man who created this newspaper and gave it its stamp of success.

Corax would spend the next 25 years working in that editorial department, first with Ranko Guzina, who would later bring Dušan Petričić into that newsroom. Speaking about that time when caricatures were inaugurated as an integral part of Novosti, he says today:

“Those were that type of caricature without an address, in which we resorted to Aesopian humour, fighting against human flaws in general terms…These were everyday themes and we worked on them every day. Over the years in “Novosti” we actually created a kind of “school of Novosti”, publishing cartoons that differed from others and from those in Jež.

I still occasionally worked for Jež, particularly in 1971, during the time of the liberals, because at that time you could really publish a lot, which was almost impossible in “Novosti”. However, with its style, Novosti stuck out compared to all other daily newspapers. There were perhaps some cartoons in other newspapers, but not even close to our quality, which was thanks to Dušan Petričić and Ranko Guzina, who was a good sketch artist, Stevo Stračkovski, Tošo Borković and, of course, little old me.”

Cartoonist Dragan Savić came up with the idea of organizing a contest for the best caricature that would carry the name of the famous Pjer Križanić. And so in 1967, the prize for the best caricature was awarded for the first time, and that competition continues to this day. Predrag Koraksić gave his valuable contribution to maintaining this competition, having served for 10 years as the commissioner of the exhibition that represented the year’s best-published caricatures. He also founded a publishing company, so when the brilliant Otto Reisinger won Pjer’s award, Corax organised the publishing of a book containing Reisinger’s caricature cartoons, under the title High Society.

Interestingly, Koraksić recalled meeting the famous Pjer Križanić during his youth:

“I was a contributor to Jež, and I was wearing some short trousers when I watched Pjer play chess with Toša Paranos, who was famous for his wit. They played chess and I, as a chess lover, stood and watched. Pjer turned around, looked at me and asked – ‘whose are you, little one?’ I was skinny, small, thin, but I remembered that Pjer addressed me and asked: “whose are you, little one?”.

That was very important to me at that moment. Many years later, director Zdravko Velimirovic decided to make a documentary film based on Pjer’s caricatures. Pjer’s best and most interesting body of work was between two kings – King Petar and King Aleksandar. Even back then it was stated in the Constitution of Serbia that “the press is free”, and Pjer had the best series of caricature cartoons that were published in dailies Politika and Novi list.

Zdravko Velimirović picked me to retouch Pjer’s caricatures for that film, and I worked on that for a full three months. I reworked his caricatures from newspapers, preparing them for shooting, and that was the best school for me. That film was shot under the title “Between two kings”, and that left a really deep impression on my career; that is my irrepeatable experience.”

Corax didn’t believe that it was even possible to destroy Yugoslavia for a long time. The realisation that it could, and everything that happened to the country, hurt him terribly. He says that he exploded creatively and it was during those years that his best and most famous cartoons emerged

Everything went well at Novosti until the time of differentiation after the Eighth Session of the League of Communists of Serbia, which represented a party showdown between Ivan Stambolić, who represented one policy platform, and Slobodan Milošević, who represented a different policy platform within the framework of the same party. As it turned out that there was no room for two such characters within the one party, Stambolić was defeated and Milošević came onto the scene, where he would stay for the next 13 years. Koraksić quickly recognised where that initiated policy would lead:

“I don’t know how or where that came from, but it was immediately clear to me what was happening and what awaited us. However, Milošević bewitched the masses; everyone was for him and with him, and I lost many friends at that time. I didn’t even want to see some of my closest relatives anymore.”

For three years at Novosti Koraksić fought against the publication’s editorial leadership. They wanted to force him to resign on his own, while he wanted them to fire him. And they were unable to fire him because the guidelines didn’t contain a clause that would allow them to do so. They finally changed the guidelines and introduced a clause whereby those who did not support the editorial policy could be dismissed. Thus Predrag Koraksić was sacked and moved to weekly news magazine Vreme (Time), where he remained until his retirement:

For three years at Novosti Koraksić fought against the publication’s editorial leadership. They wanted to force him to resign on his own, while he wanted them to fire him. And they were unable to fire him because the guidelines didn’t contain a clause that would allow them to do so. They finally changed the guidelines and introduced a clause whereby those who did not support the editorial policy could be dismissed. Thus Predrag Koraksić was sacked and moved to weekly news magazine Vreme (Time), where he remained until his retirement:

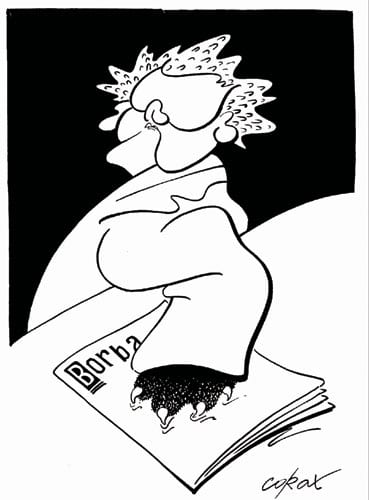

“I have a principle of no longer working for anyone who refuses to publish one of my caricatures. At Vreme that happened when Dragoljub Žarković requested that I stop drawing Vojislav Koštunica, as would also happen many years later to Duško Petričić at Politika when the editor in chief didn’t want him to draw Aleksandar Vučić. Ćuruvija [assassinated media editor and owner Slavko Ćuruvija] also did that to me while he was at Borba when he rejected one of my caricatures and I no longer wanted to work for him. This is a very famous cartoon. Vojin Dimitrijević wrote a major article for a Swedish newspaper and that caricature was published alongside his text – Milošević with a bear’s paw, placing that paw on “Borba”.

“Actually, during the three months of the bombing, I didn’t publish a single caricature.”

Austrian President Kurt Waldheim was accused in 1988 of being responsible for war crimes in Bosnia and Greece as a member of an SS unit during World War II. He had been elected President of Austria two years prior. When those allegations came out in public, he remained silent and didn’t make a public statement. Corax then published a caricature cartoon in magazine “Duga” showing Waldheim with a swastika over his mouth instead of plaster. Duga’s then censor destroyed an entire print run of 50,000 copies only to print a new version without Corax’s cartoon: “Fortunately, I was able to get a copy of that printed issue featuring my caricature”.

I supported both Čeda and Radulović, and I also supported Tadić when that was necessary, but as soon as they changed and showed their negative qualities I made cartoons that opposed each of them. It is the same case today when I make caricatures with Aleksandar Vučić as the main protagonist

Corax didn’t believe that it was even possible to destroy Yugoslavia for a long time. The realisation that it could, and everything that happened to the country, hurt him terribly. He says that he exploded creatively and it was during those years that his best and most famous cartoons emerged. He drew from his stomach, wanting to oppose the descending lunacy. He wasn’t afraid of the consequences of such a stance or of drawing caricatures whose main characters were the then holders of power. Asked whether he was subjected to threats during that time, he tells CorD:

“I wasn’t threatened directly, but rather indirectly. But I had to work just as I had to breathe, so I also had to draw. No matter what, I paid no attention to that. During the time of war, I survived all sorts of things. Our head was always in a bag, so I somehow solidified, not paying attention to that; I simply had to do that. And when Yugoslavia broke up, my real work simply gushed out of me and I was unable to stop myself, not even to this day.

I collaborated for many years at Vreme with Stojan Cerović. He wrote his text, his column, and I drew a caricature. That was always independent. I worked independently on my own and it rarely happened that the topics we covered would overlap. I remember that period as a nice time. I liked to work and hang out with him, and when he died it was really a loss for everybody, but I felt it especially.”

I collaborated for many years at Vreme with Stojan Cerović. He wrote his text, his column, and I drew a caricature. That was always independent. I worked independently on my own and it rarely happened that the topics we covered would overlap. I remember that period as a nice time. I liked to work and hang out with him, and when he died it was really a loss for everybody, but I felt it especially.”

Corax enjoyed unbelievable success worldwide during the 1990s. The New York Times published his caricatures, as did all newspapers in Germany and other European countries, and he lived from that:

“I had to go to Hungary and open a bank account there so that my fees could be paid, because they all paid me. I sold the originals of my caricatures here and they almost all sold out. I was visited by foreign journalists and foreign ambassadors who sought to buy my drawings. For instance, at that time the then Norwegian ambassador came with his wife and made a heist of my caricatures, because they both bought their own, given that they both had their own collections of pictures. I had an exhibition in Oslo and the Ambassador submitted his own collection to be shown as part of the exhibition.

”When the Milošević government was toppled in the one-day revolution of 5th October 2000, many people believed that Koraksić would be left without a topic and without a target, but he continued sketching without interruption:

“Everyone thought that I would no longer have someone or something to draw, but there’s always something that bothers me and so I will always have a reason to draw caricatures. I have an instinct to react immediately as soon as something catches my eye. I supported both Čeda and Radulović, and I also supported Tadić when that was necessary, but as soon as they changed and showed their negative qualities I made cartoons that opposed each of them. It is the same case today when I make caricatures with Aleksandar Vučić as the main protagonist. “He and other politicians from today’s scene are the fourth set of politicians that I have sketched and which I intend to say farewell to.”

I’ve always been driven mad by arrogance, which is actually a dominant characteristic of those people, ruthlessness, lies, deceit… and especially nationalism. I don’t know whether this is a consequence of me being the child of a mixed marriage, but I’ve always immediately recognised the stupidity and primitiveness of nationalism and nationalists

Corax says that his cartoons are created by looking at the world through a keyhole. His idea is to strip down political and national potentates to reveal the caricatured essence of their character:

“I’ve always been driven mad by arrogance, which is actually a dominant characteristic of those people, ruthlessness, lies, deceit… and especially nationalism. I don’t know whether this is a consequence of the fact that I am the child of a mixed marriage, but I’ve always immediately recognised the stupidity and primitiveness of nationalism and nationalists. I think that with my drawings I’ve managed to strip down these people, politicians and national potentates, to show the caricatured essence of their character. I made them ridiculous even though they were dangerous, and I would say, judging by the reactions that have reached me, that the people liked that.”

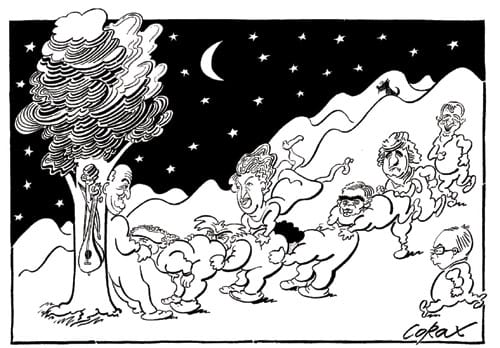

Koraksić has only once had to appear in court as a result of his caricatures. This was due to a cartoon published at the time when Dobrica Ćosić went to Pale to convince the Bosnian Serbs to sign the Vance-Owen plan. In weekly Vreme Corax drew Ćosić, Konstantinos Mitsotakis, Momir Bulatović, Radovan Karadžić, Biljana Plavšić, Nikola Koljević and Momčilo Krajišnik:

“I drew them playing a game that in my childhood called trule kobile [like Leap Frog], and the prosecutor claimed that in my caricature the protagonists were performing fellatio on one another! Realising that it would end up looking ridiculous, the prosecutor dropped the charges after three hearings. Many years later I learned that Dobrica Ćosić had called for the filing of the indictment and not Slobodan Milošević, as I had thought.”

Predrag Koraksić has left behind him a series of books in which his best cartoons are collected, while a particularly important one is the edition published by the Official Gazette under the title: “Past Continuous Tense: Chronology 1990-2001”.

Of the many testimonies of praise for his art, it is difficult to overlook the words of writer Miljenko Jergović, who wrote, among other things: “Predrag Koraksić always, explicitly, deals with the Serbian side of things. That also means the Serbian side of the war… Corax draws for Serbs and in the daily ceremony of self-reflection he does the same for his audience as was done for the Germans by Thomas Mann…”

Corax explains that his duty is to deal with the evils of government and he isn’t giving up on that.