A gentleman with a bow tie and polite manners. His poems are just the same: picturesque, aromatic, beautifully worded, romantic… He stopped counting how many books he’s published, both for adults and children, anthologies, parodies, essays… He’s edited magazines, written librettos for ballet and opera, screenplays for films and television shows… His books have been translated into countless foreign languages, while his poem “Mostar Rains” is known around the planet and recited with enthusiasm in many countries.

In our country, Mostar Rains was an interpretation challenge to reciters, actors, writers… It has been recited by Rade Šerbedžija, Gojko Šantić, Ivan Bekjarev, Gidra Bojanić, Miloš Žutić, Dragan Nikolić, Zoran Radmilović, Miroslav Antić, all in their own unique way, while experts say that it was done most beautifully by Rale Damjanović. His poems have been recited at school performances, while now they’ve have found their place in Serbian language textbooks.

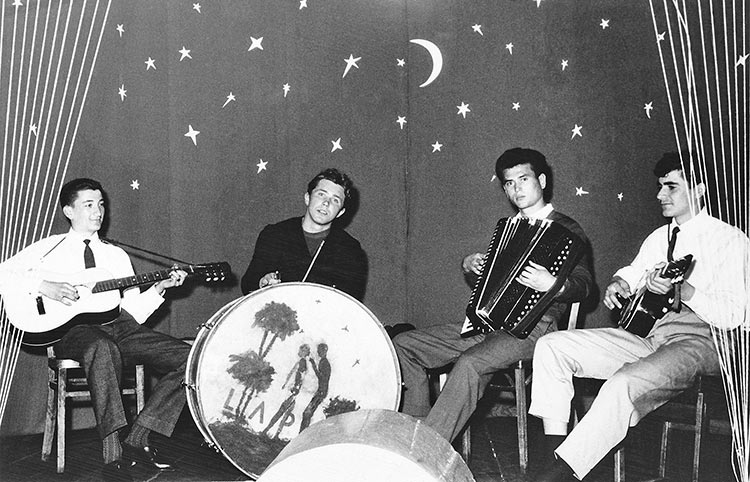

Apart from books, as a child he was also interested in sport. Specifically, boxing and football. In the Nevesinje bazaar, he formed a team for mini football, which is still talked about today. He was close to Josip Broz Tito, for which he has never been forgiven by some individuals. But that doesn’t bother him.

He has always written and read. And still does so today…

Although you were born in the Herzegovina town of Nevesinje, many think that it was in Mostar where you came into the world back in 1945?

Duško Trifunović once said, speaking at some literary forum, that the people of Nevesinje won’t forgive me for having never been a municipal writer, but rather a county one – thinking that Mostar adopted me after “Mostar Rains” and Mostar was a county and Nevesinje a municipality.

What are your earliest memories of childhood, your family, city etc.?

Back in my high school days, I memorized one thought of Vladan Desnica: “Childhood – that handful of immortality”. I still think that childhood is the cradle of naivety, innocence, the all-encompassing beauty of growing up, regardless of possible poverty and personal misfortune, if they happen during those years. I had a happy childhood, bathed in the care of five golden sisters and two sisters and two cousins. Nine children in a big house with heavy green Turkish partitions on the ground floor, lots of windows and a small city park and city cistern opposite the house. We were separated from the city post office by the Zubčev alley, which is still paved with marble dating back to ancient times, and we could hear the sound of the Jedreški stream flowing under the alley.

And then my stepmother’s son, Slobodan, who was two years older than me, arrived from his uncle’s in Nikšić. Later, my brother, a successful doctor, moved to the other coast early on. Of my sisters Zora, Milica, Danica, Janja and Bojana, and Vasa and Ljubica’s daughters, Mila and Branka, and two stepbrothers, Aca and Miloš, the only ones who are still alive are Milica in Smederevo and Branka in Nevesinje.

I still think that childhood is the cradle of naivety, innocence, the allencompassing beauty of growing up, regardless of possible poverty and personal misfortune, if they happen during those years

The town was beautiful, small, nestled in the hills. Did everyone know each other?

The postman meant a lot to me as I awaited letters from my first crushes during secondary school, from Vera from Osijek and from Ljiljana from Belgrade, two policemen, city electrician Toša Šipovac, two tailors, Vaso and Meho, photographer Senad Dugalić, two cobblers, Mišo and Sveto, two barbershops, Kazazić and Haznadarević, a hotel, two taverns, JNA [Yugoslav National Army] House and a large barracks that housed more soldiers than half the population of the town. The cinema in JNA House and Lazo Turkalj, who “played I still think that childhood is the cradle of naivety, innocence, the allencompassing beauty of growing up, regardless of possible poverty and personal misfortune, if they happen during those years films” and was, after the Pašajlić brothers, Mladen and his brother and Ilija Dugalić, goalkeeper of the football club Sloga, and later Velež. A small school for up to four classes in the centre, and with a large primary school next to the park.

The pupils’ dormitory across the street from my window, where war orphans and other kids without parents lived, the Jedreški stream, which flowed through the town like a small river, a chemist’s, clinic, doctor Muftić and dentist Jugo, several shops, Zema (Zemaljski warehouse) and lots of greenery and fields of flowers. An Orthodox church, a Catholic church and a mosque. Father Risto Mužijević, who always had silky sweets in the pockets of his robes, which he handed out to children. The garden of Salko and Emina Eminović, across the street from the mosque, was surrounded by a high wall that contained the only drinking fountain in the town. Father Obren often took me to Salko’s Garden. He and Salko would nibble on snacks, drank hot brandy, sometimes sing old Dalmatian or Herzegovinian songs. I would play with the glittering droplets thrown by the fountain onto the green rose garden. And all that remains of all that is my poem “House of Eminović”: (“House of Eminović opposite the mosque, the first sharbat drinks and the first okra, / the first Eid al-Adha and the first sacrifices, dry almonds, on the Sheriff’s chains…”)

When we enter our later years, the memories of dear people, of what we’ve experienced with them, awakens in us tenderness, special emotions… What do you keep in that album of the unforgotten?

I have been in my “later years” for a long time and my memories are still not awakened. Some things have been erased, mostly the injustices I’ve experienced in my life, or – to put it another way – repressed in the corners of memory. I remember and most often recall moments of happiness, serenity, gentleness, joy, calmness. My album of the unforgotten is large.

Glistening winters and the snows of childhood, sledge rides down the Grebak, the first films in the Nevesinje cinema, St. George’s Day holidays in Batkovići, the warm care of my sisters, my first crushes, Olga and Lola, the town library and librarian Vinko Milas, so committed and dedicated to books and recommendations for children to read, football matches and little pictures of footballers that I collected from the wrappers of chocolates, carefully and with devotion, blue flowers in the Nevesinje field, buttercup grass, the smell of elderberry and linden trees in the gardens, the first scout detachment, a carefree existence, collecting medicinal herbs (rupturewort, linden, elder, orchid) and my first earnings from submitting the plants to be sent to Belgrade, where my uncle Mile Soldo, aka Forta, was the director of company Jugobilje. And the table football that we invented and played with buttons as footballers, and my uncle was a tailor and I had the best button team, and that beautiful button with a wind jacket that sometimes came to us as Unra’s assistance, along with Truman’s eggs and plant-based cheese from America. And the snowballs were dry and soft. It didn’t hurt when they hit you.

I have been in my “later years” for a long time and my memories are still not awakened. Some things have been erased, mostly the injustices I’ve experienced in my life, or – to put it another way – repressed in the corners of memory

The Zubac family also had a house in the village of Batkovići, where your youngest uncle, Bogdan, lived, and aunt Stana with her children. It was at their place that you celebrated your family patron saint’s day of St. George and the feast of St. Elijah. The church and the faithful were frowned upon during that post-war period and people mostly celebrated “in secret”?

Vaso and Obren weren’t party members, so they were allowed to celebrate, but Obren did that at Bogdan’s place in Batkovići because he had been the director of socially-owned companies until his retirement (hotels, agricultural cooperatives, trade companies). Some ‘first fighters’ [WWII Yugoslav Partisan combatants] also came to the celebrations, and the priest came to Vaso’s, so whether we wanted it or not he would burn incense in our rooms and on the veranda. I loved the smell of incense and myrrh, and still do. That’s something you don’t forget. And every Easter, which was my favourite holiday during my childhood, I went to the church tower with my friends to ring the bell, and looked forward to coloured eggs and competing to see which has the strongest shell, then the town was full of people who were filled with some universal happiness.

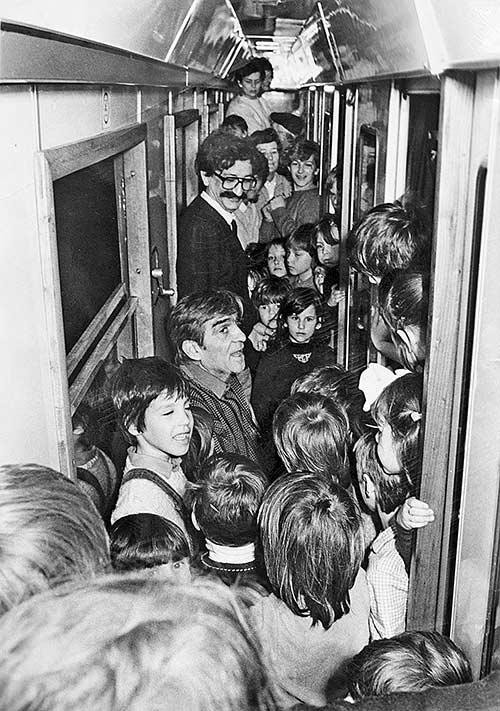

ON THE TRAIN TO SPLIT

PERO ZUBAC – VILLA RAVNE

Did you recall the Christmas and Yuletide traditions of your childhood?

I remember some holy serenity from Christmas evenings and mornings, and some blessedness on the faces of all of us who were celebrating: česnica loaf, roast meat, cakes, the scent of Christmas bread, slightly impoverished from today’s perspective of the celebrating of major holidays.

It is inevitable for certain “pictures” to be erased from our memory, but there are also those that remain forever. You mention with joy Nevesinje’s winters, snows…

In my memory, the snows of Nevesinje were a brighter fascination than the rains of Mostar, and their whiteness is described in many of my poems, especially those intended for children. There were days when buses couldn’t traverse the road from Mostar to our town. There were no sledges, except for larger sleighs that villagers used to come to the town with the help of horses, on Thursdays, on market day. The snows of childhood are my everlasting joy.

You lost your mother, Joka, at the age of just five. That is an irreparable loss, even though the widow Božana, whom your father married, worked hard to take your mother’s place for you and the other children?

I remember her only for good things. And the relatives multiplied: her brothers, the Živkovićs, Milan and Đoko in Belgrade and Ljubo in Straševina near Nikšić, sister Jela married to Vuk Nikčević, in Belgrade, their numerous children, were the new wealth of my upbringing.

And every Easter, which was my favourite holiday during my childhood, I went to the church tower with my friends to ring the bell, and looked forward to coloured eggs and competing to see which has the strongest shell, then the town was full of people who were filled with some universal happiness

You learned to read both the Cyrillic and Latin scripts early on, and the most interesting book for me was also Stanojevic’s Encyclopedia.

My sisters taught me to read both the Cyrillic and Latin scripts, so I dragged that thick Encyclopedia with me to the park and read randomly on the bench, so they say that they took me to school for the children to see a kid who knows and is capable of all sorts and isn’t yet of school age.

You mention your teacher, Ibrahim Karadž, as one of the leading lights of your childhood?

My wonderful, good teacher! We would see each other later, whenever I visited Nevesinje, and there is one interview with him in Mostar’s Sloboda, when he spoke as the President of the Association of National Liberation War [NOR] Fighters in Nevesinje, and half of the article is about me. I keep it as a dear reminder of Ibra. Recently, my extensive (beautiful, white and thick) bibliography from 1962 to 2020 was published by Gordana Đilas, and that dear bibliographic unit was also registered.

You visited the Town Library every day, to take and return the books you read. That was also an opportunity to chat with the town librarian, whose name you haven’t forgotten?

I’ve already mentioned my Vinko, whose sister Nada is married to my cousin Aca, and we actually spoke recently, and in one poem I wrote the verses “If there were no Vinko Milas, none of us who’ve been renegades of the world for knowledge would recognise our own star”.

You completed the first two years of high school in Lištica near Mostar, then later continued your schooling in Zrenjanin, at the Second Experimental High School. You spent six days a week at school, then the seventh day working on your craft?

That school in Lištica was an experiment, a type of classical grammar school where even the physical education teacher had to be a national champion in some sport. In the first year that was Petko Radović, the national champion in boxing in the bantamweight division, who I recently met in Sarajevo via my friend, handball player Mustafa Demir, after a break of about sixty years. Next to the pupils’ dormitory on the hill, with playgrounds and a large park, was a large, dormitory-type library. My beautiful Široki Brijeg years. And afterwards two years in Zrenjanin at the famous Lerik’s Gymnasium [High School]. My beautiful boarding school days, with Bogdan Gušić, my father’s friend and a journalist, taking care of me, my schoolmates, my crush Smiljana Župunski. I received the “Lenka’s Ring” award for the most beautiful love poem (“Defence of Memory”), which also preserves within it for eternity Smiljana Anja Župunski, an intelligent and beautiful girl.

In my memory, the snows of Nevesinje were a brighter fascination than the rains of Mostar, and their whiteness is described in many of my poems, especially those intended for children

When did you start writing and publishing your works?

In the second grade of high school, when I was taught literature by poet Zdravko Ostojić. I started writing poems and sent one to Sarajevo and it was published in the student newspaper ‘Dani’ in the section “Moment of Poetry”. The title of the poem was “Sadness”. The year was 1962.

Which poets and writers did you love in your youth, and whose manuscripts do you read today?

Yesenin, Mayakovsky, Pasternak, Šantić, Dučić, Rakić, Dis, Ujević, Cesarić, Desanka, Kaštelan, Sarajlić, Antić, Raičković, Trifunović, Leso Ivanović, Georg Trakl, Dylan Thomas, Walt Whitman, Miklós Radnóti, Nichita Stănescu…

I read contemporary poets, I receive many manuscripts with a request for a recommendation, I write the odd essay, order books that I would like to read from publishers. In the last few days, I received a new novel as a gift from Geopoetics: Iron Curtain by Vesna Goldsworthy. It is such an intoxicating book that I stop reading so it will stay with me for the next few days. The only other book I remember reading like that was Death and the Dervish by Meša Selimović.

Although you wrote about Mostar, you never actually lived there. This was perhaps best described by your fellow writer, friend and comrade Duško Trifunović, in the preface to Neđo Šipovac’s extensive monographic study?

“The best poet from Mostar, after Aleksa Šantić, is Pero Zubac, who passed through Mostar when travelling from Nevesinje to Široki Brijeg, where he attended school. There he wrote his love story, and then that love story became a term for Mostar and Mostar’s singing. Interestingly, there was nothing there. There were some things, but they didn’t cross the regional ramp…” Duško in typical Duško style!

You wrote the love poem Mostar Rains in 1965, out of boredom, with no inkling that it would make you famous. While you were waiting for your friend and fellow poet, Rade Tomić, to write his poem on the premises of the then Youth Organisation in Novi Sad, you threaded a sheet of paper into a typewriter and wrote those famous verses in one go?

It was a September evening. I didn’t have indigo and I typed it in one copy. And that night I posted it to Zvonimir Golob, the editor of Telegram in Zagreb. He published it under the name Perica Zubac, which was how I signed it; that’s what everyone in Nevesinje called me, on 8th October, 1965. If that letter had gone astray, if Zvonimir had forgotten it, that poem would not exist. He told me once, long ago, that he would include it in his anthology of world poetry, which he unfortunately didn’t manage to finish and publish during his lifetime.

Although that legendary poem won over the sympathies of critics and readers, you didn’t include it in your first book of poetry. You only did so at the insistence of your then professor at the Faculty of Philosophy, Dr Draško Ređep?

Draško Ređep wrote about me several times, very affirmatively and beautifully, and for one article about me, entitled “Breath of Youth” and published in Politika, he was awarded the Milan Bogdanović Award, the top prize for literary criticism in our country. His last essay about me is included in his selection “The Most Beautiful Poems of Pero Zubac”, published by Belgrade’s Prosveta in 2004. I most like this passage from his preface: “… And finally something very, very personal. In the half-light of the former building of the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad’s Njegoševa Street, I was approached by a young man in a long coat, resembling Prince Myshkin, absolutely absent, to be read as dedicated, and asked me to agree to his seminar paper on Dis. Who knows, maybe it was because of that purple and Novi Sad twilight that the new Dis visited me. I never asked if Zubac wrote that seminar paper on the poet of murk, riddles and secrets. But, in essence, the overall solution of this lyricist, so aloof, so dedicated, was that supposed seminar paper. Students have long since been our modern classics.”

(Draško was no longer at the faculty, and I published the paper in two instalments in Novi Sad student newspaper INDEX).

Mostar Rains’ Svetlana was an intriguing character. Everyone wanted to know the identity of this girl, who still makes this poem magical. The poet initially said that Svetlana does not exist, then later revealed that Svetlana is a non-existent girl who was woven into the poem on the basis of the characteristics of Mirjana Šimić from Mostar, Ljiljana Njanje Canić from Belgrade, Vera Steiner from Osijek and Dragana Vajdić from Novi Sad, who later became your wife.

The answer is in your question. Of those four golden girls from my early youth, I composed Svetlana. All “platonic” loves.

I received the “Lenka’s Ring” award for the most beautiful love poem (“Defence of Memory”), which also preserves within it for eternity Smiljana Anja Župunski, an intelligent and beautiful girl

Irina Chivilikhina’s Russian translation of Mostar Rains was published in Moscow magazine Robotnica (1988), which had a circulation of 19.75 million copies. Your poems can also be found on other Russian sites and with “Orwell”, alongside Njegoš and Goran Kovačić. Mostar Rains was also published on a Finnish website, alongside two Desanka Maksimović poems.

The internet extended the literary life of Mostar Rains, multiplying it a thousand times, and it has been translated into 20 world languages. Belgrade publisher Admiral Books published the jubilee edition in 2015, in thirteen languages, then another translation was published in Polish, then in Hungarian, Spanish, German, and the most recent, from 2019, in Bulgarian.

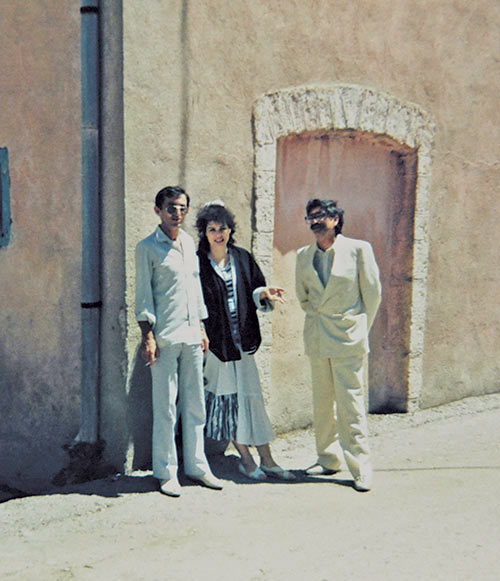

You didn’t visit Mostar for a long time. You only returned to the city on the Neretva in 2005, after a decade and a half away, with the book Return to Mostar. That was unforgettable for you and for guests and visitors?

As noted by my friend Milan Gutić, who drove me there and followed me throughout my stay in Mostar: “Unrepeatable. Now, and never again like this”. The evening was beautified by the Mostar Rains Ensemble: Mišo Marić, Šerif Aljić, Kemal Monteno, the Planjanin brothers… Poetry lovers from both banks of the river flocked to the National Theatre.

That success was repeated at the book’s promotions in Sarajevo and Banja Luka. Was that the reason for you to continue writing that book?

In Sarajevo, Gradimir Gojer, my dear friend and then President of the BiH Writers, said in his welcome address that my arrival in Mostar and Sarajevo meant more to the citizens of Bosnia- Herzegovina than all the visits of politicians from around the world and the region combined. And Raif Dizdarević confirmed that writing in Oslobođenje: “I had dinner with Pero and Slavko Pervan, but the magic ended with Pero’s return to Novi Sad”.

You didn’t move to Novi Sad with the intention of staying there, yet you’ve lived in that city with your family since 1963?

I came and stayed. I never regretted that or had a desire to change the city where I live.

Novi Sad is the city of your past and present. You have wonderful sons, Vladimir and Miloš, and grandchildren, Milena and Mey, to whom you are particularly attached. That is joy, while there is also sadness. Many of your nearest and dearest have long since departed to join the infinite. Apart from your wife Dragana, they include Miroslav Antić, Duško Trifunović et al?

My family: Nataša and Vladimir, Dragana, Miloš, Milena and Mej and I are like one being. So different, fortunately, and so close, fortunately. We protect one another.

It is becoming increasingly clear to me that my concerns over my health, the dream of longevity, is not about hope that I will add something to my artistic name, but rather that I will spend longer in the embrace of the family and watch my grandchildren, Milena and Mej, beautify and extend my life.

Many of my friends are on the “other shore”, together with my Dragana. In my dreams I most often encounter Antić, my stepbrothers, my Duško and Dragomir Brajković, an old friend and generational sibling, and everyone in those dreams is happier and more relaxed than they were in our life, which is not at all easy and as bright.

It’s tough to list all the awards that you’ve received. Could you single out some of them without doing harm?

With the latest three: the ‘Biblios Lifetime Achievement Award’, the ‘Sretenje Order of the Second Degree for Services to the Republic of Serbia and its Citizens in Literature, Especially Poetry’, and the Award of Banja Luka’s Children’s Kingdom Festival, ‘Prince of the Children’s Empire’. The total number is three more than the number of years I’ve lived.

Do you still write and, if so, what?

After the children’s poetry book Poems for Milena, for which I received the province’s highest award for children, ‘Sima Cucić’, I’m transposing the manuscript of the book DEDOLOVKA – poetry book for Mej, and I’ve submitted a book of poems from recent years, entitled “My sister – loneliness”, to Vesna Goldsworthy to write me a foreword, and she was glad that we will “be together in one book”. It will be published by my new precious publisher, Tomica Karadžić, owner of Grafoprint from Gornji Milanovac, who prior to the new year published a wonderful edition of the poetry book Defence of Memory, along with Miloš’s book of selected and new poems “Returnees to Love” and Miloš’s selection of Duško Trifunović’s poems, “Save the one I love for me”. Miloš is very much following in his father’s footsteps. And that makes me feel very proud.

By Zorica Todorović Mirković