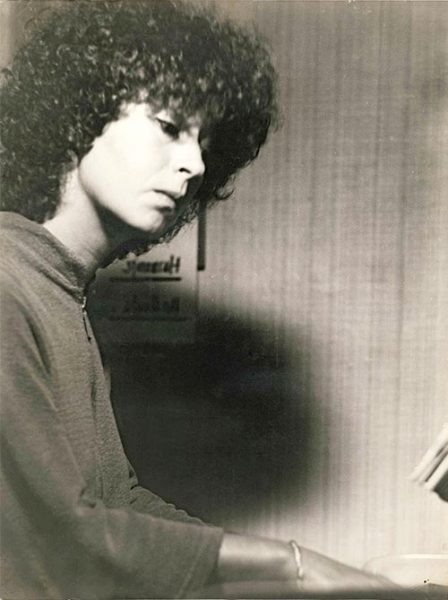

She is among the most important Yugoslav and Serbian composers of contemporary music, an essayist, a former successful director of BEMUS, the Belgrade Music Festival, and a former state secretary at the Ministry of Culture, but also one of the founders of the BUNT festival, which carries the motto ‘musical REBELLION [BUNT] against an obedient society’. Her grandfather was doctor, poet and translator Svetislav Stefanović, her grandmother was Milana Bota Stefanović, who studied pedagogy and psychology in Zurich and was a descendant of a family of minor nobles from Transylvania. Ivana is the daughter of aesthetician and writer Pavle Stefanović and professor of the piano Vera Bogdanović, while she is also the mother of a successful daughter

She played the violin as a child and enrolled in the Music Academy at the age of 17. She was simply predestined to pursue a career in music. She never considered what she would do, as it was a given that she would deal with music. Her first student composition, Three Movements for Piano, was performed together with works by students of the Academy of Music Arts at a concert held in the building of the old Atelje 212 theatre. She completed composition studies in the class of Enriko Josif, studied the violin in the class of Aleksandar Pavlović and completed her studies on a scholarship from the French government in Paris. Her works have been performed in Yugoslavia and other European countries, in Israel, the U.S. and Russia, but also in Kazakhstan, Syria and elsewhere. She has written the musical scores for more than 40 theatre plays that have been performed in Belgrade at the National Theatre, the Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Atelje 212, Zvezdara Theatre etc. Of these works, we will mention only Aeschylus’s Oresteia, Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet, Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Svetlana Velmar Janković’s Dungeon…

I was personally present when she got her start in the late 1970s, in the TV Belgrade show Music Atelier, which I hosted together with the composer Zoran Hristić. Her radio drama project Veliki kamen [Great Rock] led to her receiving the international Prix Italia award for radio and television creativity in 2017, and during that same year she received the Stevan Mokranjac Award for the same work, and this is just a small part of the recognition she’s received during her more than four decades of creative work. Ivana (born 1948) spent a lot of time with her father Pavle Stefanović, who was a member of the circle of versatile Serbian intellectuals that included the likes of Stanislav Vinaver or Milan Kašanin, and who wrote art and music critiques and literary essays. He was among the first to support abstract art and its revolutionary characteristics on the territory of the former Yugoslavia. Pavle considered his gifted daughter as a serious interlocutor from an early age:

“My upbringing was completely atypical and non-standard. As a little girl, my father took care of me while my mother taught piano lessons at the Mokranjac Music School. My father took care of me from behind his typewriter while I had fun under his desk, or by talking to me about the topics that occupied his mind and about which he thought: he recounted books to me (Camus, Sartre etc.), read folk poetry to me, explained music or described the script of some theatre play he’d just read. We lived in two rooms of a shared apartment, which meant that not a single word could be said between my parents or their friends without me overhearing. They were very nice intellectual but completely ordinary conversations, because their friends included extraordinary people, mostly artists, writers, composers and actors, but also a peasant woman from the market who brought cheese. That was a time of hope that people are equal, regardless of race, colour, religion, atheism or education. This was the source of that idealistic attitude about people as brothers from Schiller’s Ode to Joy, which was later used for Beethoven’s composition.

In my young days, women artists, women managers and women editors were ubiquitous. Some important female artists came to our house and my father considered them more than equal

“That puzzle all came together somewhere. And today I know where it is – it’s in me. Interestingly, the family in which I was raised was also pressed by everyday problems, and in that sense was quite ordinary.”

Such a family ensured that she was taught humanism, empathy, understanding and, if necessary, how to help others. The power of reason and the virtue of imagination are things that her parents tried to pass on to her.

Ivana has a daughter from her first marriage, Ana, a sociologist who graduated from Princeton and received her master’s degree in Switzerland, where she lives today. She is highly educated and, like many of today’s young people, speaks several languages:

“Her work sees her meet people and communities that are different from us, that have some other customs and other gods, and are often poor. She is great with people, not only in her work, and I’m immensely proud of her. I don’t think she would approve of me ‘advertising’ her more than this.”

Ivana has spent a long time married to Zoran S. Popović, a retired diplomat who served as ambassador to Jordan, Syria, Turkey and Romania. After her time resident in Syria, she published the book The Road to Damascus, which emerged as a formatting of her notes from that country:

“I didn’t write a book, but rather notes that were supposed to help me memorise a completely new region, and that’s the Middle East. When my residence in Damascus came to an end, I thought it could potentially be a book. Writing music and text strikes a very good balance. While doing one I take a break from the other, or develop a desire for the other. That dual road suits me.”

Ivana’s book Private Story is particularly interesting. On more than 500 pages, it presents a family saga that emerged on the basis of 8,000 pages of handwritten manuscripts that were left in her aunt’s suitcase, and which details the histories of her Bota and Stefanović families. While following the trace of these documents, Ivana supplemented the story about them. There is also the exceptional character of Ivana’s grandmother, Milana Bota Stefanović, a student of psychology and a surrogate doctor, as well as writer Svetislav Stefanović:

“The book Private Story, according to the contents of one suitcase, emerged during the period when my husband was in his fourth and final consecutive ambassadorial mandate, this time in Romania. During my more than three years resident in that country, I focused first on research for this book and then on writing it. But from the outset it wasn’t clear to me what I was getting myself into. That family suitcase that I mention in the title was full of documents, letters and other papers that I transferred from Belgrade to Bucharest when we left. What I wanted to do appeared to be completely harmless; when people retire, they should sort out their inherited papers. It was only when I started working that I realised that I would have to write a book, because the documents testified to much more than just one family. They documented Serbian society and the language, politics, relations between individuals, political parties, prices, funerals, marriages, major events and wars through which the small lives of ordinary people were broken; about culture, education, girls who wanted to study, celebrities, but also completely uncelebrated individuals.

I wouldn’t like to idealise that time when there were all sorts of varied things going on, but the issue of women’s equality was a reality in socialism

“The biggest challenge of the research was the distant past, and that occurred right there, in Romania, because life conspired to give me a signpost in that suitcase confirming that one branch of my distant ancestors hailed from Transylvania (Erdelj). That’s how I arrived in the 16th century, when King Sigismund Bathory gave those ancestors Hungarian noble titles and they became nobles, receiving a coat of arms featuring a raven on a branch with grass in its beak.”

Ivana’s grandmother, Milana Bota Stefanović, was an extremely highly educated young girl for her time. Among the correspondences, Ivana came across descriptions of her trips to theatres, her careful selection of books, language learning, participation in sports, travels abroad to familiarise herself with foreign cultures, piano lessons that turned her into a pianist with an enviable repertoire… In Zurich, where studied pedagogy and psychology at the University, Milana also gained several life-long friends, among them Mileva Marić, who would soon become Einstein:

“Still, I don’t have the impression that my grandmother Milana was special in some way. She simply had an upbringing for which she should be congratulated, but so should her parents.”

Ivana’s grandfather, Dr Svetislav Stefanović, was murdered in October 1944 and the site of his grave remains unknown to this day:

“I’m happy to be able to announce that my grandfather, Svetislav Stefanović, was rehabilitated a few days ago by the Assembly of the Serbian Medical Association, with the restoring of all rights that belong to a president of the Serbian Medical Association over several mandates.”

I always went my own way in my creative work, quite isolated. I also feel good when I remember who I brought to Belgrade as the artistic director of BEMUS, and particularly when I see a dozen young people with autism singing in a concert as part of the BUNT festival

It is logical to ask how difficult Grandma Milana found it to secure her liberty in a society that was ruled by men? Ivana offers a priceless answer:

“Ever since I took a little peek into history, I consider things as always being much more complicated than they seem. We have today all fallen into the trap of simplifying everything due to an excess of comfort. Yes, the 19th century was the century of the male society, but I believe that certain individual men – fathers, husbands – were the bearers of progress for the female members of their families. As I today consider the first emancipatory moves taken by girls and women by going to school and college, I always see that the initiators of the idea of their equality were men, emancipated parents, fathers, brothers or husbands.

“My grandmother Milana had a father who directed and hugely appended her education already in her young days. That father highlighted to her what was happening in the world, informed her where women’s schools were opening or where girls were being allowed to enrol in university. I will repeat that it was the huge educational capacity of her father, Dr Pavle Bota, that was the force that opened the way for this girl. I saw that same matrix repeated with my father’s support in the case of Milana’s close friend Mileva Marić, as well as in the case of many other girls of that time.”

Here it is interesting and important to include a quote from the book Private Story, from the notes of grandmother Milana regarding Milena Marić Einstein, the great Serbian scientist and wife of Albert Einstein, with whom she was close friends during her studies in Zurich from 1898:

“Marić visits us often. She’s a very good girl, but overly serious and laconic. One wouldn’t even say that she has such an intelligent mind!”. “Marić has just now again introduced me to her good friend. He’s German and his name is Einstein. He plays the violin wonderfully, it can be said that he is a Künstler [artist], so at some point I will have someone to play with again…” and “Marić came to see me again with that German and we spent the entire afternoon playing music.”

Ivana’s great-grandfather and Milana’s father, Dr Pavle Bota, apart from being a doctor, was also a talented artist. He sang exceptionally well and already performed as a school pupil, and even received enviable reviews in the newspapers. Apart from that, he was an extremely modern man, with a strong sense of social justice, who at one time was even involved in politics and served as a member of parliament in the Serbian National Assembly.

According to the assembly records that Ivana found in the Archives of Serbia, from the assembly he successfully advocated for the opening of schools and spa centres. So, he was interested in the topics of education and health, but was clearly aligned with progressive European movements. The description of her father makes it easier to shed light on the personality of Milana herself.

I don’t know about other SANU departments, but what I see with those that have connections with art, literature and culture is the dominance of conservatism and closedmindedness, both professional and aesthetic

Speaking about herself, CorD’s interlocutor says that, unlike her grandmother Milana, she lived in a different time, and didn’t live in a world ruled exclusively by men. She didn’t have the feeling that her gender disqualified her, nor that she was deprived of equality:

“In my young days, women artists, women managers and women editors were ubiquitous. Some important female artists came to our house and my father considered them more than equal. That same father encouraged my first creative impulses. I know that some people might be dissatisfied with this answer, but I link that feeling of equality with socialism. I wouldn’t like to idealise that time when there were all sorts of varied things going on, but the issue of women’s equality was a reality.”

Composer, essayist, Radio Belgrade editor, BEMUS festival director, state secretary at the Ministry of Culture, one of the founders of the BUNT music festival… all of these form parts of Ivana’s rich career. She felt at her best when she had the most problems, which is what gives her the greatest sense of pride from her biography:

“I now have a long view of my life, so I can be less critical of myself than I once was. I’m not even angry with myself for my short excursion into state structures. It was then that I got acquainted with part of the depth of the cultural (as well as non-cultural) being of our country better than I had before.

“I mostly like to think about my works, in radio and music, books, radio plays, installations and generally the titles that I created and thus preserved the fire of my ideas, musical thoughts and imaginings. I have an equal love for those works that received some of the many awards as I do for those that didn’t. I just had a concert of my string quartets from the 1969- 2015 period. I gladly compare this event with a retrospective exhibition. I’m satisfied that I didn’t entertain passing trends of taste and fashion in my work, and that I don’t have a single dedication that I would like to tear out.

“I always went my own way in my creative work, quite isolated. I also feel good when I remember who I brought to Belgrade as the artistic director of BEMUS, and particularly when I see a dozen young people with autism singing in a concert as part of the BUNT festival. I’m also satisfied with my modest attempt to do something for Serbian contemporary music and my older and younger colleagues by dealing with the New Sound Spaces tribunes, but also prior to that, at the Ministry of Culture.

“Otherwise, I don’t believe that my career was particularly rich. I just worked as much as I could, dealt with art at night while my family slept, and generally nurtured a kind of faithfulness, intellectual, artistic, professional and human.”

It is well known that the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) is quite closed when it comes to accepting women among its membership. Ivana was among last year’s nominations that were overlooked, or, more precisely, no woman was selected to join the Art Department. Many are prepared to suggest that misogyny is rife in SANU, and this distinguished composer says it’s a fact that women are obviously not very welcome in Serbia’s oldest national institution:

“Why women artists and cultural workers aren’t welcome at SANU is almost a humorous question. Well, it’s because they aren’t welcome! I wouldn’t want to talk about myself, as I’m not a good example at all, but it seems unbelievable to me that the Art Department would allow itself not to have a single female music creator, now after the death of Isidora Žebeljan. At the same time, the group of women composers has been extremely numerous in our country for years, or even decades, and has been artistically active and strong, both at home and on the international stage. Suffice to say that of the 24 recipients of the biggest award in the field of art music, the Mokranjac Award, nine have been female composers. And I will mention only two ladies who are extremely representative of Serbian music culture: Aleksandra Vrebalov and Ana Sokolović.

We’re now living in a time of lies, loud, blind untruths that have taken over. Everything that’s black is becoming white, every fact is turned into a falsehood: history and historical figures, language, heroes, worldviews… That has led to me becoming obsessed with the truth

“Believe it or not, but I’m not particularly interested in what SANU does. However, the very fact that I was nominated by my Association, together with three of my male colleagues (Milan Mihajlović, Zoran Erić and Srđan Hofman), made me curious to at least monitor what was happening with our candidacies. And what I grasped: that work there is according to some informal groups, that there are a lot of phone calls and lobbying. I don’t know about other SANU departments, but what I see with those that have connections with art, literature and culture is the dominance of conservatism and closedmindedness, both professional and aesthetic.

And another thing is that it seems much worse to me that the best didn’t enter SANU this time either, regardless of gender.”

Ivana has always been vocal when she’s had to defend and advocate for the improved status of artists in society. What is it that hits her the hardest today as an artist, as a person, and makes her feel bad in Serbia today?

“I’ve always felt like a minority. The fact that I deal with art music only fortifies that feeling in me. When I work, I listen, invent, imagine; I live in a parallel world and surround myself with fictional layers… And that isn’t an uncomfortable position at all, until the terror of the majority begins.

“We’re now living in a time of lies, loud, blind untruths that have taken over. Everything that’s black is becoming white, every fact is turned into a falsehood: history and historical figures, language, heroes, worldviews… That has led to me becoming obsessed with the truth. We have seen the emergence of a social disease that’s called a lack of reason and an excess of self-pity. In that space where everyone purportedly hates us, there’s been a development of self-sufficiency, neoconservatism, a complex of false greatness, grandomaniacal conceit and xenophobia.

“However, the basic thing that grips me with icy fear is ignorance. I hope that someone or something will try to stop this ignorance very soon, otherwise… I’ve said enough about the past here, but I’m actually much more interested in what’s coming.”