He is descended from the Polish Jews. Klajn is actually German surname Klein, quite common among Jews. His maternal grandfather, Mihajlo Đurić,was the president of the Chamber of Commerce, highly regarded as an honest and hardworking man among Belgrade locals. During World War II, it was grandfather Mihajlo who saved him and his mother, while his father Hugo hid from the Nazis under the assumed name of Uroš Kljajić

As a child, Ivan spoke German, French and English. He earned a degree in Italian, learned Spanish but chose to dedicate himself to Serbian. His views on language-related issues that emerged after the disintegration of SFR Yugoslavia are invaluable. He believes that the most accurate concept, and the one deeply rooted in Slavistics internationally, is that different varieties of the same language were spoken in all parts of Former Yugoslavia except in Slovenia and in Macedonia. The trouble is that we don’t have a common name for that language.

His father, Hugo Klajn, was a renowned neuropsychiatrist. Born in Vukovar, he studied in Vienna where he attended the lectures of the even more renowned Sigmund Freud. After the war, he became a stage director and a lecturer at the Belgrade’s Faculty of Dramatic Arts. Ivan’s mother, Stana Đurić Klajn, was a pianist, a secondary school teacher at the Music School Stanković, and later a musicologist and a director of the Institute of Musicology of the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences (SANU).

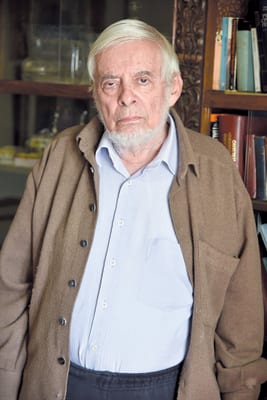

Ivan Klajn (80) was born in Belgrade. He was introduced to foreign languages by his parents. When he enrolled in the Faculty of Philology in 1956, he chose Italian as he was already fluent in French and German, but he would also take all the books on the compulsory reading list from the faculty’s British and American library. His PhD thesis was “Influences of the English Language on Italian”. He taught Historical Grammar of the Spanish Language at the Spanish Department and wrote the textbook.

Ivan Klajn (80) was born in Belgrade. He was introduced to foreign languages by his parents. When he enrolled in the Faculty of Philology in 1956, he chose Italian as he was already fluent in French and German, but he would also take all the books on the compulsory reading list from the faculty’s British and American library. His PhD thesis was “Influences of the English Language on Italian”. He taught Historical Grammar of the Spanish Language at the Spanish Department and wrote the textbook.

He started writing about the modern Serbian language for Borba in 1974. He then went on to write for Ilustrovana Politika, the culture supplement of Politika and for NIN, whose contributor he has been the longest, since the early 1990s until today. He compiled his articles into eight books, two of which (The Sidetracks of the Meaning and Words are Tools) were published by NIN.

Ivan Klajn has written 29 books, the most important of them probably Word Formation in the Modern Serbian Language, in two volumes. The Dictionary of Language Conundrums, published by various publishers, has had eleven editions while his Italian-Serbian Dictionary has had five. The somewhat smaller Serbian Grammar for Foreigners was published by the Textbook Bureau. It is also available in Italian (Grammatica della lingua serbia).

Ivan Klajn has written 29 books, the most important of them probably Word Formation in the Modern Serbian Language, in two volumes. The Dictionary of Language Conundrums, published by various publishers, has had eleven editions while his Italian-Serbian Dictionary has had five

In 2000 he became an associate member and in 2003 a fully-fledged member of SANU. He is the chairman of the Serbian Language Standardisation Board, founded by Pavle Ivić in 1997. He is also a member of the Italian Accademia della Crusca in Florence.

Without a doubt, Ivan Klajn is today the greatest authority among linguists, an expert extraordinaire in the Serbian language and a mandatory interlocutor when it comes to language-related subjects and dilemmas.

No newspaper, weekly or monthly magazine seems to write about the language as continuously as you have done for years for NIN?

– Serbian media have a fairly long tradition of writing about language norms. Even before World War II, Politika’s journalist Živojin Bata Vukadinović had a column “Serbian in 100 lessons”, which was then made into a book whose second edition, updated to the new Serbian orthography, was printed after the war.

In the mid-1950s, Politika’s language column was written by Miodrag Lalević, and today, though sporadically, by Rada Stijović. Kosta Timotijević used to write a similar column for Borba. He was the one who first introduced me to the job. A number of useful language guides were written by Bogdan Terzić, Drago Ćupić and Egon Fekete, and in Sarajevo, in cooperation with Serbian publishers, by Milan Šipka.

In the mid-1950s, Politika’s language column was written by Miodrag Lalević, and today, though sporadically, by Rada Stijović. Kosta Timotijević used to write a similar column for Borba. He was the one who first introduced me to the job. A number of useful language guides were written by Bogdan Terzić, Drago Ćupić and Egon Fekete, and in Sarajevo, in cooperation with Serbian publishers, by Milan Šipka.

In recent years, under the initiative “Let’s preserve the Serbian language”, Politika has published dozens of articles in which our linguists give language-related advice. The Ministry of Education has a similar initiative titled “Let’s cherish the Serbian language”. Radio Belgrade has a five-minute daily programme called “Serbian in Serbian”, where the radio station’s copy editors give competent language tips with a good sense of humour.

Finally, there is “Voyage into Words”, a Radio Belgrade 2 programme hosted by our linguist Vlado Đukanović and his associates. In all of this, I don’t think I’m an exception to the rule.

Which of the Serbian media seriously care about the correct use of language?

– I must admit that there are many newspapers and magazines that I don’t follow at all. By the time I’ve read NIN I don’t have any time left for other weeklies, and I don’t even look at the tabloids. However, I think that Politika, the oldest newspaper in the Balkans with a serious cultural tradition, takes first place.

In post-war Yugoslavia language issues, like everything else, were under the control of the Communist Party, and the first open disputes started emerging only with the awakening of Croatian nationalism during Croatian Spring in 1971, and later

This is the only newspaper I know of that has a solid team of proofreaders, lead by Gradimir Aničić. Not that long ago it was customary to credit the copy editor in the Impressum. Not anymore. It is quite possible that many magazines don’t even have a copy editor but rely on their journalists’ education.

Is the correct use of language as big a problem in countries with a long cultural tradition such as England, France, Germany and Italy?

– Certainly not, because although their languages are spoken in more than one country, they have solved the standardisation issue back in the 19th century. In the Balkans, however, due to historical circumstances such as conflicts both in the first and second Yugoslavia, the disintegration of the country, and especially the collision of the two branches of Christianity (Orthodox and Catholic) and two scripts (Cyrillic and Latin), the common Serbo-Croatian language became polycentric and caused numerous disagreements ‒ not impossible to resolve but they are not being resolved ‒ with opposing views even on the language name and terminology.

How limited, poorer is the modern language compared to the one used, say, 40 years ago? Or is it richer?

– It’s definitely richer. The development of civilisation and technology have brought along a myriad of new phenomena, customs, inventions and discoveries. Whether we have an appropriate name for each of these novelties, is another question. In Serbia, like in the rest of the modern world, the tendency is to casually and automatically adopt English words, even where a suitable translation can be found.

In Croatia, however, the traditional Croatian purism, which was born out of protest against the German influence at the time when Croatia used to belong to Austria, is as powerful as ever. This is why the revived Croatian norm now requires that even international words such as ambassador or patrol, known to every Croat since the beginning of time, be replaced by coined Croatian words veleposlanik and ophodnja, respectively. There are plenty of similar examples.

In your opinion, when did the first serious language-related problems start in Yugoslavia?

– In the first years after the 1918 integration, they were not taken seriously at all. The idea was that the national languages would automatically merge into one simultaneously with political unification. Some even claimed that “Serbo-Croat-Slovenian” was the language spoken in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes although every Slavist knows that Slovenian is a specific language with specific literature. Macedonian was also overlooked.

– In the first years after the 1918 integration, they were not taken seriously at all. The idea was that the national languages would automatically merge into one simultaneously with political unification. Some even claimed that “Serbo-Croat-Slovenian” was the language spoken in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes although every Slavist knows that Slovenian is a specific language with specific literature. Macedonian was also overlooked.

Bulgarians regarded it as a dialect of their own language while Serbs considered it a dialect of southern Serbia, although, in reality, it is a transitory type of language: like Bulgarian, it doesn’t have declensions, but it’s closer to Serbian phonetically and lexically. In post-war Yugoslavia, language issues, like everything else, were under the control of the Communist Party, and the first open disputes started emerging only with the awakening of Croatian nationalism during the Croatian Spring in 1971, and later.

What was the role of the so-called 1954 Novi Sad Agreement? Who criticised the Agreement immediately after its signing, and why?

– The Novi Sad Agreement was a natural extension, concretisation and realisation of the famous 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement, where Serbs and Croats agreed to speak two varieties of the same language, to share the Neo-Shtokavian dialect and two accents (Ekavian and Ijekavian), but to use two different scripts.

Since then up to the early 1910s, the so-called “Vuk’s disciples” were the most influential group in Croatia, first and foremost Tomo Maretić. Three rather logical projects were agreed in Novi Sad in 1954. Matica srpska and Matica hrvatska, the two oldest cultural institutions in Serbia and Croatia respectively, were to jointly publish a common orthography book in 1960, which was going to replace the 1892 Croatian Orthography by Ivan Broz and the Serbian Orthographies by Belić published after WWI and WWII.

They were also to publish a multi-volume dictionary of contemporary Serbo-Croat and compile common terminology (this never even started). Sadly, in the early 1970s, the Croatian Spring was born, chauvinist aspirations took over in Matica hrvatska and the Croats stopped working on the dictionary after its second volume (while Matica srpska completed it, publishing its six volumes in 1976, and more recently, in 2011, its one-volume version).

Instead of the common orthography, several competitive versions of the “purely Croatian” orthography were published in Croatia. The way the things are now, it is highly unlikely that the planning of a joint Serbian and Croatian version will ever happen.

There wouldn’t be any problems just as there weren’t any in either of the former Yugoslavias if they were not brought about artificially to deepen political conflicts among the former sister republics. This is why these problems should be solved by politicians and lawyers while the linguists should provide expert assistance

What is your opinion of the recent Declaration on Common Language? It has caused quite a stir in the countries in the region it concerns – BiH, Serbia, Montenegro and Croatia. Does it have any significance for the future?

– The Declaration justifiably highlights some undeniable facts that have been blurred by nationalistic prejudices. The only people who kept drawing attention to them were Ranko Bugarski in Serbia, and Snježana Kordić in her book Language and Nationalism (opposing the official Croatian language policy) in Croatia.

The fact is that there is no ‘equals sign’ between a language, a nation and a state, that it is not true that “every nation has the right to call its language by its own name”, and that the use of the same language in different countries, by different nations is a common occurrence worldwide (the best examples being English, Spanish and Portuguese, to which we can add French, Italian and Arabic).

Then there is the criterion of intelligibility. Snježana Kordić argues that if two language communities have 70 per cent or more common lexemes, they do not speak two different languages but two varieties of the same language. In our case, mutual intelligibility is well over 90 per cent.

Therefore, the most accurate concept and the one deeply rooted in Slavonic studies internationally is that different varieties of the same language were spoken in all parts of Former Yugoslavia except in Slovenia and in Macedonia.

The trouble is that we don’t have a common name for that language.

The once-suggested “Illyrian” was neither acceptable nor scientifically justifiable because, as we know, Illyrians were not Slavs. The most widely-accepted in Slavistics was Serbo-Croatian (with possible variants for domestic use: Croat-Serbian, Serbian or Croatian, Croatian or Serbian), and it went without saying that it included Bosniaks and Montenegrins because a four-barrelled name would have been impractical.

The once-suggested “Illyrian” was neither acceptable nor scientifically justifiable because, as we know, Illyrians were not Slavs. The most widely-accepted in Slavistics was Serbo-Croatian (with possible variants for domestic use: Croat-Serbian, Serbian or Croatian, Croatian or Serbian), and it went without saying that it included Bosniaks and Montenegrins because a four-barrelled name would have been impractical.

Modern foreign politicians, especially those in the Hague, circumvent the problem by using acronyms such as BHS, BCMS and the like, but an acronym cannot be a scientific term. When our common country disintegrated, terms such as “Bosnian” or “Bosniak” were invented but there is no real justification for them. The only difference is that Turkish and Arabic words are used somewhat more frequently (which, by the way, are not uncommon in Serbia or Croatia) and the sound /h/.

Talk about “the Montenegrin language” has no justification whatsoever. They have added two purely dialectal phonemes (the palatal /s/ and /z/ sounds) just to create an artificial difference. The Declaration highlights all these nationalistic diversions, supporting them by the fact the mutual intelligibility is still nearly one hundred per cent and that no-one needs translations of Croatian books into Bosniak, of Serbian films into Montenegrin, etc.

What, in your opinion, is the greatest problem concerning the use of Serbian, Croatian, Bosniak and Montenegrin in the countries that once comprised SFRY?

– There wouldn’t be any problems just as there weren’t any in either of the former Yugoslavias if they were not brought about artificially to deepen political conflicts among the former sister republics. This is why these problems should be solved by politicians and lawyers while the linguists should provide expert assistance.

The logic and the facts of the Declaration should be integrated into legislation as much as possible. There is that well-known case of the Bosniaks from Novi Pazar who wouldn’t accept the charges brought against them until they have been “translated” into “their language”. If we were to read out the charges to them and ask them, word by word, which of them they didn’t understand, provided they responded honestly, they wouldn’t be able to name one. I think the legislation prescribing that a foreigner or a national minority member should get a charge written in their own language could be amended to say that this doesn’t include mutually intelligible languages.

What is the real importance of Cyrillic today, and who do we have to defend it from?

– There is no practical importance but it is important from the cultural and political point of view. I have always argued that the percolation of Latin script into Serbia is not a result of a cunning plan of domestic traitors, communists, Croats, Soros or NATO supporters and the like, but a historical phenomenon that gradually develops and becomes stronger because the national community doesn’t pay attention to it and is not aware of the dangers that come with it.

Between the two world wars, under the influence of the so-called “left-wing intelligencia”, the number of books and magazines in Latin script in Serbia was constantly growing. It seemed to make sense that in a unified country we could use either of the two official scripts as we pleased, and the publishers didn’t mind because it meant a bigger market for them.

I have always argued that the percolation of Latin script into Serbia is not a result of a cunning plan of domestic traitors, communists, Croats, Soros or NATO supporters and the like, but a historical phenomenon that gradually develops and becomes stronger because the national community doesn’t pay attention to it and is not aware of the dangers that come with it

Even then everybody knew that a literate Serb could read both Cyrillic and Latin, and that Croats didn’t know Cyrillic or were allergic to it (but no one asked why nothing was printed in Cyrillic in Croatia). When you have two tools for the same purpose, you will not be using them alternately.

Instead, you’ll stick to the one that has wider use. Latin script is more universal not because it is used in the countries much bigger than ours but because we in Serbia need it too for maths, physics and chemical formulas, for websites and email addresses, for car registration, for Latin quotations, for marking chords and as other symbols in music, and for many other things.

In addition, there is a “common” Latin alphabet of 26 letters, without any additional symbols, and history would have it that this particular alphabet was adopted by the English language, the undisputed language of global communication today, while all other languages using Latin script (except Dutch) have to add diacritics: two dots in German, accents and tildes in Roman languages, hyphens and hooks in Slavonic languages using Latin script.

Cyrillic scripts, however, are all national. Our letters “љ”, “њ”, “ђ”, “ћ” and “ј” do not exist in other Cyrillic languages, Russian has nine letters that we don’t, and is similar to the Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Macedonian Cyrillic scripts.

In practice, we see that people living in Belgrade have turned to Latin script. Not only are most shop signs in Latin (which may be for commercial reasons) but handwritten adverts and notices on tree trunks and pillars, handwritten notes that we exchange with each other where we write friends’ names, addresses, information on cultural events, recipes, letters (emails and handwritten ones), etc, etc.

To forbid or penalise the use of Latin script would be unthinkable in a democratic society. So the only thing that remains is to protect Cyrillic as a cultural good, to make it compulsory in official and public documents, to give an incentive to publishers who still publish in Cyrillic. However, we should avoid making Cyrillic a “sacred”, “ceremonial” script used only by the state but not by the people.

Is language today as important for national identity as it used to be in the 19th century?

– Probably not to the same extent because of the globalisation that has happened in the meantime. Radio, television, the internet and other innovations have helped us communicate more with the world rather than just within our own national community. However, there is no doubt that language will remain an important element of national identity ‒ although neither the only element nor the crucial one.