As a cardiologist, he was the first in the world to implant some of the most modern types of pacemaker. As a professor at the University of Belgrade Faculty of Medicine, he has shown generations of future doctors the best path. As a writer, he has published around a dozen novels, two of which were shortlisted for novel of the year. As president of the Government of Serbia’s Commission for Cooperation with UNESCO, he warns that cultural genocide is currently underway, through which the historical, cultural and religious heritage of the Serbian nation is being alienated and stolen to the advantage of the Albanian nation. As a father, he is proud of two successful sons: Dejan, a cardiologist; and Arsen, a philosopher and mathematician.

There are people who use their knowhow to reach the very top of the profession that they pursue. There are others who ennoble the human soul with their talent. But there are also those who, as great erudite people, educated and wellmannered, represent the best product of a society.

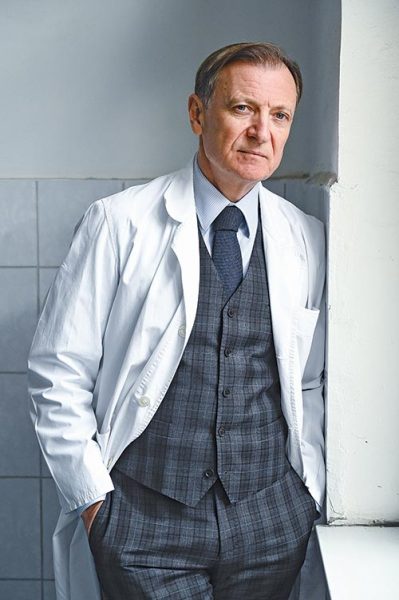

Goran Milašinović (62) is today just such a valuable person in Serbia, one composed of numerous qualities – a cardiologist, a full professor at the Medical Faculty in Belgrade, a writer and member of the Serbian PEN association, and president of the the Government of Serbia’s Commission for Cooperation with UNESCO. He was the first in the world to implant some of the most modern types of pacemaker. He is also among the few world experts whose name is engraved on one promotional model of a modern pacemaker.

He made his literary bow in 1997, with the epistolary novel Voltin luk [Walt’s Arc], which he authored together with celebrated director and writer Živojin Žika Pavlović. He went on to publish around a dozen novels, of which Camera obscura and Absinthe were shortlisted for the NIN Award for Best Novel of the Year. He is a winner of the Branko Ćopić Award for prose book of the year for his novel The Vinča Case (2017).

He is the father of two successful sons: Dejan (cardiologist) and Arsen (philosopher and mathematician).

We are determined more by the cultural patterns in which we grow up, and according to which we are mentally and intellectually formed, than just our birthplace

Born in Đakovo [Slavonija, Croatia], he grew up and completed his primary and high school studies in the Croatian city of Osijek, only to arrive in Belgrade in 1977, to study medicine, where he has remained. Recalling his early childhood, he notes that his father was a strict and ambitious lawyer, Ćopić’s funny uncle and two likeable uncles – who were, each in their own way, his first male authority figures. He says that the upbringing he received at home and the one he took away from the area where he lived, Coratia’s Slavonia, intertwine:

“We are determined more by the cultural patterns in which we grow up, and according to which we are mentally and intellectually formed, than just our birthplace. In my case, that’s a blend of a bourgeois family in Yugoslavia, the Austro-Hungarian spirit that could be felt in Osijek and Belgrade’s simple innocence and directness, but also internationalism, so I’m apparently an example of the hybrid structure typical of our area, which carries within it the Central European and Oriental, and rational, and mystical, and fatal. Here we’re all Vienna, Venice and the Levant, some more, some less, myself included.

His generation did not have the opportunity to feel the magic of Woodstock, which our interlocutor was terribly sorry about, but he was awaited by Dylan, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple… but also our first rockers. Books were, and remain, his inexhaustible source of knowledge, while for him rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t just music, rather also a cultural pattern, poetry, social engagement, world politics:

“We in Yugoslavia, unlike the Eastern European states of the Warsaw Pact, largely had open access to world flows and trends, including music, film, new theatrical tendencies and contemporary literature. Thanks to that, we grew up and got to know the world in a way that was very close to our contemporaries from the West, which was very fortunate and unexpected for a communist, autocratic state. I was interested in everything, but I mostly stuck to books, because I immediately felt that was my future “world”. I remember Remarque’s war novels, filled with psychological and emotional nuance, as an example of literature that attracted me at the very start of high school, even before books that were compulsory reading, but also books on psychology, by Erich Fromm or Karen Horney, for example, which I “devoured”. It was then that I realised that it’s not possible to get to know man and the world only materially, through biology, physics, history and science, but that literature is also important, which describes personalities and events through its resources, narration and psychological and effective analysis.

We in Yugoslavia, unlike the Eastern European states of the Warsaw Pact, largely had open access to world flows and trends

“And when it comes to music and film, my time was the time of the so-called New Wave, our punk rock scene, which was more passionate than it was authentic, given that it culminated, sooner or later, with ‘Comrade Tito, we swear to you’, or worse still, it melted away into some oxymoron wonders, like folk-rock or turbo-folk. Likewise, FEST [the Belgrade International Film Festival] opened our eyes to the world, with the best films in the world teaching us about the time in which we lived, political events, Vietnam, the “deep state”, small, faraway nations, although FEST could perhaps have done more, by bringing forth some school or forming a specific creative direction, and not just remaining as the new capital event for displays of vanity. I would say that, as a generation, we had opportunities and could have done more than imitate the West, but our creativity was killed by excessive conformism.”

It was chance that wanted Goran to enrol in studying medicine, and not architecture. Just as his specialisation in cardiology was not determined by any special intention, rather again by chance. He was actually more attracted to architecture than medicine, but the order of entrance exams during that summer of 1977 determined the further course of events. He first took the entrance exam for Medicine, and easily found himself among the first on the list of future students. Apart from rationality, medicine also attracted him because of some sublime mysticism that’s hidden within it, and that also fit with the cultural pattern in which he grew up, with discipline and order, which is very close to medicine:

“My naive view of medicine (given that I didn’t have any doctors in my immediate family) has changed in the meantime, now I see much more humanity and empathy in it than science, or at least just as much, or actually that of an individual and specific patient, but as a person as a whole, and not only partially, through disease and diagnosis, which has similarities with literature due to immersion in the psyche and soul of man. I think young doctors should take some sort of “empathy test”, and anyone who’s unable to empathise and understand the patient should change their profession while there’s still time. In return, the doctor receives pure, sincere intangible gratitude, which fulfils and inspires.”

For Goran, medicine and literature, or writing, represent two parallel tracks on which the train of his life moves. At the time when he was just making his start in medicine, he wrote a collection of poems entitled Unexplored Pains, but he soon devoted himself to writing prose and has remained faithful to that to this day. When he delved deeper into medicine and his literary work, he often found himself on the brink of physical and mental exhaustion, but he somehow managed to maintain harmony, despite him being aware that a debt will inevitably have to be paid for such an overstrained life:

“Writing wasn’t a matter of choice. It happened spontaneously. It was early on that I felt that creative pleasure of inventing characters, plots, the imitative world. But not everyone who feels the “call of literature” becomes a writer. Serious work is required; there’s a lot that a writer needs to learn and improve on, from style and form, to the choice of topics and content, because, as Llosa says, and as Andrić similarly said, the writer has a responsibility to the reader to write well, as best he can. That’s why writing is a difficult profession, which demands seriousness, energy and dedication, and not fun, in which some people see only the infantile development of the imagination and the need for stories. My problem is that I thus found myself in two serious and demanding professions, but I never experienced those circumstances as a particular burden, except that I had to reduce many spheres of life, primarily social. Not that I had a choice, because whatever else I could have done, by giving up either medicine or literature, I would have been awaited by a sense of dissatisfaction and the feeling of an empty, unfulfilled life.”

I think young doctors should take some sort of “empathy test”, and anyone who’s unable to empathise and understand the patient should change their profession while there’s still time

Under the conditions of a civilisation in which abbreviations are increasingly used instead of words and sentences, Goran, like many other writers, fears for the future of books. He believes in man’s deep need to convey his thoughts to another man. That’s something that we were born with as a species, that’s how homo sapiens functions:

“There will be literature as long as there’s a need for a person to convey a thought to another. If that wasn’t there, literature wouldn’t even exist, but just as forms of the written word have changed throughout history, we’ve had books since Gutenberg’s press, and just as we wrote and read before him, so it will also change in the future, and we are now on the threshold of the change from paper to electronic form. The real problem is the lack of interest in learning, deeper analysis, detailed reading, given that new generations are enslaved to superficial “omniscience”, pseudo-information, and they use the benefits of the cyber world to achieve competence without serious work, which is pseudo-competence (everyone knows “everything about everything”). But of that they read little, although sales of book aren’t declining significantly, just as queues for borrowing books from libraries aren’t reducing, which means that those who do read are reading increasingly more. But one shouldn’t deceive ourselves – only five to ten per cent of the general population has ever read, with the rest being educated and formed with the help of visual media, which once upon a time meant mostly television, while today it’s the internet. Quite simply, it is human nature to choose easier paths and shortcuts. We also shouldn’t forget that we live in the time of Nietzsche’s Curse, the world of nihilism, materialism, excessive individualism and terrible selfishness, which by no means represents fertile ground for spiritual activities, such as reading and literature.”

Even before this interview for CorD, Dr Milašinović said that the COVID-19 viral pandemic would lead to 20 per cent of the population experiencing some mental disorders. It is very important to prepare for that, and to combat it. That’s because it seems that humanity can’t exist without some plague. When we don’t have wars and famines, then we have epidemics. This plague imposes itself on a specific a time and calls for complete discipline, given that the only thing we know about this virus is how it is transmitted. He describes it as a kind of Decameronesque time. Just as Boccaccio imagined at the time of the great bubonic plague epidemic, when man must be confined to a small space and find a way to survive until it passes:

“Twenty per cent of the people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder is a rough estimate on the basis of experiences with humanity’s previous global traumas, though perhaps it will be even more. The reason is clear: first, fear for one’s own life; second, the complete stripping of routine and violent abandoning of habits; and third, the breaking of communication with other people, which is just as important a need for humans as the need for freedom. However, the problem is that some manifestations of PTSD are more difficult to notice, such as anxiety or mildly depressive behaviour, meaning that essential professional help – in the form of pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy – is often lacking and permanent adverse consequences remain. In other words, anyone who feels the need for a psychiatrist should seek one. But we can take some preventative actions ourselves, such as by creating a solid inner world, composed of small pleasures and hope that unfavourable circumstances will nonetheless pass, which will protect and defend us from more serious psychological harm.”

At the proposal of Professor Darko Tanasković, former Serbian ambassador to Turkey, the Vatican and UNESCO, Goran was selected to be the president of the Serbian Government’s Commission for Cooperation with UNESCO. The work of all members of this national commission is voluntary, with members having a desire to contribute as much and as well as possible to the recognisability of Serbia through numerous UNESCO activities in the fields of science, culture and education. The most important thing for Dr Milašinović is the fight to preserve the cultural identity of Serbia, because he sees that as the best way to preserve the country’s national identity. We asked him what the most difficult thing in that work is, if we take into account the fact that some of the country’s most important national cultural monuments are located on the territory of Kosovo:

“We need greater awareness of the importance of cultural identity, and with the example of our cultural assets from Kosovo we see how causally and consequently they are connected with national identity. In this regard, cultural genocide is currently at work in Kosovo, though which the historical, cultural and religious heritage of the Serbian people is alienated and stolen to the benefit of the Albanian nation, since the previous project to destroy Serbian traces there failed. That’s why the Commission for Cooperation with UNESCO considers this topic as being the most important at the moment, but also why it emphasises the importance of monitoring all other programmes and projects that increase our visibility within UNESCO and raise our standing/image, which we need on all fronts, including the political.”

Goran Milašinović’s novel The Vinča Case is particularly interesting to the local public, given that it received the Branko Ćopić Award and was inspired by the little-known fact that on 15th October 1958, during an experiment in Vinča, six scientists belonging to the team tasked with making an atomic bomb were irradiated! The irradiated atomic scientists were transferred to Paris for treatment, and were the first in the history of medicine to undergo a bone marrow transplant. That’s why this doctor and writer was so preoccupied with this topic:

On the basis of experiences with humanity’s previous global traumas, twenty per cent of the people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder is a rough estimate, though perhaps it will be even more. Anyone who feels the need for a psychiatrist should seek one

“When I started dealing with that topic in 2009, I realised it was about a series of paradoxes. Firstly, very little was known among us about something that was so important, such as the first organ transplant in the world, and performed on our unfortunate atomic scientists from Vinča. Moreover, some of the atomic scientists affected by that radiation were still alive at the time, but they weren’t inclined to talk about it and share their memories. It was as though they’d imposed a deliberate vow of silence on themselves from within. Secondly, it isn’t stated anywhere in medical scientific literature that this was the first bone marrow transplant in the world, although it was. However, it was unfortunately unsuccessful, as back in 1958 nothing was known about the importance of cell compatibility between donors and recipients, and all transplants led to transplant rejection, but they fortunately survived (except one of them) because they weren’t irradiated with a lethal dose of radiation. And, thirdly, the emphasis was erroneously placed on Vinča and the unfortunate irradiated atomic scientists, rather than on the five Frenchmen who, risking their lives, donated their bone marrow to complete strangers from behind the “Iron Curtain”.

That all seemed like the ideal foundation for literature to me, and that fact that it was based on a real-life event, instead of pure documentary or some “credible recollection”, considering that only literature has the power to penetrate the emotional and mental states of those courageous Frenchmen, as well as anticipating their character. That was the reason why I published the novel Rascepi [Split] in 2011 and The Vinča Case in 2017, which observe the same event from two different literary perspectives. The film based on the novel The Vinča Case, which is being prepared by Dragan Bjelogrlić, will shed light on this event with a new artistic language and give it another dimension, one that’s more attractive and popular than literature, so my initial premise – that something so important for us and the world shouldn’t be forgotten – will be realised to an even greater extent.”