We are a country that has seven million inhabitants, and we have Vojvodina, Mačva, Šumadija, Pomoravlje, and with all that we have a million hungry people. If we are not capable, we should immediately lease the country to someone to feed us.

Lease it to someone and ask him to employ us, because we’re not capable of doing that for ourselves. We live in a country that imports beans. Miloš Obrenović is certainly surprised in his grave, asking: Where has the golden dinar gone that was there when I ruled the country? At one point we imported brooms from Albania and brushes from Bulgaria. When you “export brains”, then you import brooms

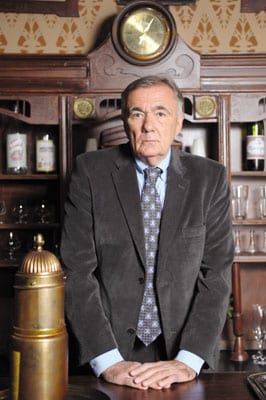

Continuing the tradition of Sterija, Nušić and Popović, and sometimes in co-vibrations with the poetic dramas of Ljubomir Simović and the humour of Matija Bećković, Dušan Kovačević has raised Serbia’s bitter comedy to the highest level and become a European value of the first order – noted the members of the jury that recently presented the Ivo Andrić Award to writer and academic Dušan Kovačević (69) for his entire oeuvre and the drama Hipnoza jedne ljubavi (Hypnosis of one love).

“The Ivo Andrić Award is particularly dear and important to me because this is, I hope, deserved recognition after almost half a century of work and that’s why it rightly bears the Lifetime Achievement title. For me, this is all exciting and a little surreal, given that more than sixty years have passed since I started school when I learned the first letters which I later wrote in my work. Like many generations, I grew up with Andrić’s books,” responded this author of around twenty dramas and a dozen screenplays, this writer who authors stories and novels.

Dušan Kovačević also wrote the screenplay for the best Yugoslav and Serbian film of all time – Ko to tamo peva (Who’s singin’ over there) – and is the owner of the dramas that gained the most popular among the nation – Radovan III, The Marathon Family, St. George Shoots the Dragon, The Balkan Spy, The Professional, The Hilarious tragedy, Larry Thompson, Five-Star Container and other works, all the way to his latest drama, Hypnosis of one love, which was recently performed with huge success at Belgrade’s Zvezdara Theatre and is currently invited for guest performances in a dozen cities and at several festivals. He is a member of the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences and director of Zvezdara Theatre.

Kovačević was born in the village of Mrđenovci near Šabac. He attended primary school in Šabac and completed secondary school in Novi Sad, after which he came to Belgrade by train, clambered up Balkanska Street, caught a bus at Zeleni Venac and reached the final terminal in Zemun, then walked for another ten minutes to reach his relatives, with whom he lived in the Zemun colony:

“I spent a few months there, and then I found a room in New Belgrade. From that first room to my address today, I changed 20 addresses. I say in jest that there isn’t a street where I haven’t lived. I know that by chance because I received letters and one day I looked through those letters that I preserve and compiled a list of my Belgrade addresses during these fifty years that I have lived here.

Mihiz was one of the most precious people I met in Belgrade, and the most important person to me privately. If not every day, then certainly a week doesn’t pass in which I don’t remember him. And I always have the same question: what would Mihiz say now, what would he do?

“Those were rooms with good people, rooms with irritable people, rented apartments where my wife Nada and I lived, first alone, then with our first child – our son Aleksandar. When our second child was born – our daughter Lena – we were finally in our apartment.”

Kovačević has lived for a long time in Senjak, or on Topčider Hill, as those who live there prefer to refer to it. He lives in the house where famous Serbian writer Isidora Sekulić was a tenant and where she spent the last 18 years of her life:

“I’m glad that I managed to save the threshold of this neglected and ruined house – everything else collapsed.

“During her lifetime this threshold was crossed by the likes of Crnjanski, Crnjanski, Andrić, Meša Selimović et al, and during my life by Mihiz, Bob Selenić, Matija Bećković, Bata Stojković, Žika Stojković… and most important artists of the second half of the twentieth century.

“Thus, this threshold has been crossed by the history of Serbian culture in the twentieth century.

“And I bought the house accidentally, and it was earmarked for demolition.

“Of course, I am convinced that all of that was not “accidental”; I was “brought” to save it.”

When he thinks about his childhood today, he says that one of his main fears in early childhood and adolescence was the fear of death. As a five-year-old boy he suffered from meningitis with lung complications, which was a serious disease that could have ended in tragedy and usually ended in such a way: “I rememdied that fear by writing The Marathon Family, and it is no wonder at all that a 22-year-old would sit down and write a story about coffins, wreaths and a funeral home. That was actually my release from and resistance against that accumulated fear. Writing is a personal psychotherapy. You treat yourself as you write, solve some problems and make a confession on that paper. Sometimes that’s good and interesting to someone else, but sometimes it remains only for you, and you end up throwing away most of those papers.”

He authored his first text in the fourth year of high school for a Radio Belgrade competition in short story writing, received a prize for his work. When he graduated, he wrote a short story that resembled a novel, with which he passed the entrance exam for the Academy of Theatre, Film, Radio and Television, today’s Faculty of Dramatic Arts. However, he explains:

“Immediately after passing the entrance I destroyed that manuscript. And I destroyed everything I once did that I later didn’t like. I still do that today with things that I think aren’t the best. Writing is erasing, while something worthy also remains.”

One man who was important in Serbia’s 20th-century culture, writer Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz, played a major role in the life of this writer. As a student of dramaturgy, Kovačević was fortunate enough for his first play, The Marathon Family, to be read Mihiz, performed at Atelier 212, and directed by Ljubomir Muci Draškić:

“Mihiz was one of the most precious people I met in Belgrade, and the most important person to me privately. If not every day, then certainly a week doesn’t pass in which I don’t remember him. And I always have the same question: what would Mihiz say now, what would he do? Whenever I was in doubt during his life, whenever I didn’t know what I would do, I would call him on the phone and would always repeat the same sentence:

“Sir, I have a little problem. I would like to ask you what you think…”

And he would always give the same answer: “And why does it concern you what I think?”

“Mihiz was the first to read my new dramas, all the way until his departure. After his death, I had a major misunderstanding with myself. I could no longer take my texts to him; I could no longer hear the remarks that he would say to me. And I often recall how, after the first premiere, after The Marathon Family, while I stood at the bar in Atelier 212, attempting to figure out what was happening, he said “Relax and rejoice. This is your first and last premiere.”

I looked at him, according to that rule that advice is listened to in order not to be accepted, as Mihiz himself would say, and it was not quite clear to me what he meant by that. I realised it all a little later, that same year when I had my second premiere at Atelier 212, Radovan III.

That was already a different feeling, only for everything to later turn into “already seen”.

“I never again experience the excitement of that first premiere, neither in Belgrade nor elsewhere in the world.”

As a man who built a system of values, not only in his family but also among those who watched and remembered the monologues and dialogues of his plays, he now sees all the bad sides of life that are lived ever faster and more superficially:

“People watch television mesmerised all day, with its increasingly destructive and morbid reality shows. They foster vulgarity and a lack of culture, contempt for everything that is human. It is absurd, but unfortunately true, that it is today an insult to be an educated man. The more educated a man is, the more he is a nincompoop because he has wasted his life learning, reading, dealing with worthless things. In short, he has not managed to do anything great. And the term great today implies only grotesque material goods, the grief and misery of vulgarity. I guess that’s why these young and brilliant mathematicians of ours seem like a confusing incident. And that’s why they will, like many before them, leave to go work somewhere where their knowledge is valued… I don’t know if there are some other countries where there is the generally accepted characteristic: clever man, and a fool.

They foster vulgarity and a lack of culture, contempt for everything that is human. It is absurd, but unfortunately true, that it is today an insult to be an educated man. The more educated a man is, the more he is a nincompoop, because he has wasted his life learning, reading, dealing with worthless things

If we consider that politics stands behind everything said today, that is not true, because today’s politics is merely the result of the previous policy. That which happens in 2017 or will happen in 2018, is merely the result of the systematic destruction of the nation since 1944. If you arrive in “liberator’s” uniforms in a city like Belgrade, and in that city, within a period of just a few months, you shoot between 9,000 and 13,000 of the most valuable and most educated people, and replace them with semi-feral tribes that have wandered into that city, you have decapitated a nation, yo have killed what was best. That band came, brought by mindless commanders, led by war criminal Josip Broz, who was never tried. This is immediately linked to the unfortunate converting of an agricultural, agrarian country into a party-based, workers’, semi-industrial, semi-social creation that was financed externally for as long as that was necessary. When Josip Broz died, if he died, he was succeeded by Milošević with the same arrogance, but in completely different historical circumstances. We had two men who thoroughly destroyed Serbia. What we are living today is just a result of the dictatorship of domestic and foreign powers. The bill arrived and none of the debtors is there to pay it, so it is being paid by the people.”

In order to be able to write his latest play, Hypnosis of one love, Kovačević spent 20 years collecting data that primarily relate to young people who have abandoned the country. When Tito first opened the borders of the former Yugoslavia, a million of them left, about which the writer says:

“Gone are the young, the brave and the clever. Who’s left? Those who stayed are those who are scared and those who are party members. I once met 11 of our young people at the Hotel Sheraton in Montreal, half of whom were from Dorćol. One of them, who was not yet 30 at that time, was the hotel’s PR. And that’s what it’s like all over the world. In the nineties, under Milošević, 200-300 thousand of the most educated young people left, forever. And that’s why today you cannot create a serious company, enterprise, government. Simply, we lack people. There is a Serbian football league and a league of players who play abroad. The team that’s abroad is incomparably better. This with athletes is only symbolically more obvious, but the essence is the same: when the best leave, the average remain. Novak Đoković cannot cure all of our defeats, even if he won in other sports.”

Claiming that we only have ourselves to blame for the bad moves that have been made for decades by people in positions of power, CorD’s interlocutor explains:

“We are a country that has seven million inhabitants, and we have Vojvodina, Mačva, Šumadija, Pomoravlje, and with all that we have a million hungry people. If we are not capable, we should immediately lease the country to someone to feed us. Lease it to someone and ask him to employ us, because we’re not capable of doing that for ourselves. We live in a country that imports beans. Miloš Obrenović is certainly surprised in his grave, asking: Where has the golden dinar gone that was there when I ruled the country? At one point we imported brooms from Albania and brushes from Bulgaria. When you “export brains”, then you import brooms.”

This member of the Crown Council and opponent of the Milošević regime does not hide his disappointment with the policies pursued in Serbia following the so-called democratic changes:

“After 5th October 2000, everything that had been stolen during the nineties was legalised, which meant that the new democratic government legalised theft. Our many years of walking and protesting on the streets were, as it turned out, pure nonsense. Like clowns, we participated in a circus called ‘let’s take down the government for things to be better for them’. And when we did, we found that those who were generally sitting in their houses and offices had already made businesses. They were capable, on the fly, of engaging companies and factories, privatising everything that was even remotely worthy. I know several people who came to the theatre in the ‘80s and ‘90s and had money only for one drink. But today they are among the wealthiest people in Serbia and the Balkans. How; where from? Well, it would be that they handled the situation. And handling (snalaženje) is our beautiful word for theft and crime.”

After 5th October 2000, everything that had been stolen during the nineties was legalised, which meant that the new democratic government legalised theft. Our many years of walking and protesting on the streets were, as it turned out, pure nonsense

Asked whether he believes in what Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić does and promises to do, Kovačević responds:

“And what else is left for me? I’m certain that he wants to do what he says, that he wants to do things, but I don’t know whether or not he will be able to do that. I’m afraid that we and our fate is decided by major powers, as always.

If he succeeds in bringing order to state institutions, creating trust in a fair, legally regulated state, he will have achieved a “revolutionary step” toward a better life. He is awaited by a large, tough and long job in the country of Serbia, where the greatest risk comes if you change something and work a lot.”

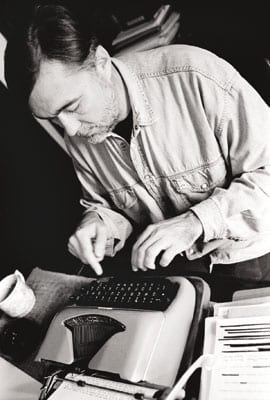

Kovačević has no mobile phone and does not use the internet or a computer. Until fifteen years ago, he typed his texts on a Pearl typewriter. However, its letter began to fall off, so he had to weld them back on:

“A friend brought a welding iron during the bombing of 1999 and we welded the letter R, because for some reason that broke off first. Then I bought an electric machine. In fact, I write texts by hand, revise them, then retype them, do the corrections, then my wife enters that into a computer so I can again read and correct them. And that happens a few times.”

Duško admits that the mobile phone is a fascinating technological advancement, but his resistance to this miracle can be boiled down to the following:

“I generally have a bad relationship with technology. When I press the light switch, the light bulb is bound to burn out. Electricity eludes my world, though I love light and consider it the greatest of all phenomena in the world.”

“And when it comes to mobile phones, this little freedom that I have, which is an hour or two a day, would be revoked by such a device in my pocket. I would be on standby and would constantly be in a pre-cardiac arrest condition due to the feeling that I am late. I am by profession paranoid because I live from writing and paranoia, and whenever I would hear that device I would search and look, and I would find that not one call would be important or urgent enough to replace that two hours.

Look, for instance, at my character Ilija Čvorović from Balkan Spy. He, as a luckless person, had to carry a pair of binoculars, to torment himself, to fall from trees while following suspects. Today nobody would send him to do this. He would be unnecessary because the services now follow people through their mobile phones. Thus for me, it is absurd to pay for some device that spies on me; to carry it with me and voluntarily announce myself, to report on myself.”

Since he first married, Duško has had one woman beside him – Nada. Nada is a lawyer, but since she married Duško she has taken care of her husband and children. Strong, intelligent, educated and interesting, Nada is the pillar of the home and is beyond the reach of the public.

Duško travels exclusively to places linked to the sea. He likes to spend his summers in places where he can still dive. He also still plays football twice a week:

“The four of us started playing football together almost forty years ago. We remained from the team from the times of Vračar during the early 1980s. And we actually started playing football at the Academy, as students, as actors had to have some physical activity so they decided that would be football. I joined them. Generations and generations have passed through our football socialising… even Emir Kusturica played with us for a few years while he was resident in Belgrade.”

During one football match at the Sports Centre in Zemun, on 16th January 2012 at 6.45 pm, Kovačević survived a heart attack. He had two stents implanted, recovered and after some time had passed, continued as before:

“The fear and panic of surviving the symptoms and surviving the disease lasted for several months, until I want to the seaside with my wife, put on my flippers, donned a mask and dived two meters, for no reason, just to free myself from listening to my heart.

“And today I still play football with my friends, twice a week, as if nothing happened. Some doctors say that’s crazy, while some, on the contrary, thinks it’s just fine, provided I don’t run like I did when I was 20… I listen and respect both of them, and I live as I have always lived – according to laws, rules, feeling and the will of the Almighty.”

As a father, Kovačević is very proud of his children. He is satisfied with what they chose to do in life and the way they live – his daughter Lena graduated in jazz singing at the Music Conservatory in Amsterdam, his son Aleksandar lives in San Francisco, graduated from college and now works in finances:

“My children achieved the maximum from what they had as living conditions. They used everything they had at birth, and Nada and I considered that we should enable them to achieve what made them feel good as soon as possible, for them to go their own way without any restraints. Our daughter and son are actually just like every parent would want their children to be – they completed serious schools and succeeded in fighting to achieve their existence, which is very important. And that is one of our biggest successes as a home.”

Since he first married, Duško has had one woman beside him – Nada. Nada is a lawyer, but since she married Duško she has taken care of her husband and children. Strong, intelligent, educated and interesting, Nada is the pillar of the home and is beyond the reach of the public

In recent years Duško and Nada have been enjoying themselves as grandparents of three boys and one girl.

With a lively interest in what is happening on the political scene in Serbia, but also elsewhere in the world, he comments on the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States:

“I enjoy that story. I’m simply happy because America deserves Trump. He did not happen to them by accident. In this heavenly story, there is some justice. These protesters, especially the stars from Hollywood, I never saw on the streets threatening to blow up the White House because of the bombing of Iraq. And these immense columns of unfortunates, just in the last year several thousand of whom even drowned, are a result of the domino effect from Iraq. They all watched that calmly, having no problem with all the crimes committed by U.S. foreign policy, so Trump comes as something that is a kind of mild retribution for everything, which they actually deserve. Trump is now trying with some merchant’s rationality to see what will pay off and what won’t. And that is his policy. I would like for him to receive a second term.

“This is not me cheering for the man called Donald Trump. This is only my wish for the foreign policy of America to stop waging wars all over the world. They bombed Serbia twice in the 20th century: during the Easter of 1944 and for three months in 1999.

“Is that sufficient to explain why I said what I said about the new president of America?”

Please click here for the Serbian version of the interview.