Dragoljub Zamurović is the author of numerous photo monographs in which he preserved the beauty of the landscapes, countries and cities that represented the splendour of the former Yugoslavia and today’s Serbia. He recorded the horrors of the war of the 1990s, demonstrations and student riots, and made portraits of politicians, but he most likes reportage features as a journalism genre. He’s had a cover page of Time magazine and realised his childhood dream of having one of his photos published in Life magazine. He was interested in the life unfolding around him and despised politics and politicians who failed to fulfil their preelection promises

At this moment when I’m working on this article for CorD with him, he has a photo reportage published in the current issue of National Geographic magazine, under the headline Falconry in Serbia. It was worked on for precisely a year by Dragoljub Zamurović (73), a graduate architect and photography artist, and published over 18 pages in National Geographic. This is actually the tenth reportage feature of this artist to be published in this renowned world magazine, and it received the Best Edit Award that’s presented for the best local production in the network of National Geographic magazine.

Zamurović is known to the general public for his numerous photographic monographs in which he presented the most beautiful landscapes of numerous countries, regions and cities. His oldest known ancestor was named Georgije Zamur, who came to Iđoš in 1692 from Mesopotamia, via Asia Minor and Greece.

Born in Niš, he was less than eight years old when his parents moved to Belgrade. They’d had a large three-room apartment and backyard in Niš, but upon arrival in Belgrade had to live in a 14-square-metre apartment together with his father, mother, brother and grandmother. Thankfully they didn’t stay there for long, as his father took out some loans and they exchanged the apartment for a bigger one. His grandmother died and his brother emigrated, first to Belgium and then to Australia. He lost two sisters early on, so the age difference between his oldest brother and him, as the youngest, was 13 years.

“My parents were very lenient with me. I suppose that was because they lost two girls and my brother left home, they did everything for me, both what they should have and what they shouldn’t. I had all the freedom that a child can have. I loved insects when I was a child. I collected them next to a street light in Niš, which they flew towards in the evenings. I hadn’t started going to school yet, but I would often stay until after midnight to wait for them and catch them. I also liked to go there to play very early in the morning. There I would find a group of boys who would go home after a while, and I would join another group and stay with them. Sometimes I stayed like that all day, without lunch and without fear of being scolded for that.”

Zoran Đinđić understood photography and its significance, while Milošević and Koštunica didn’t

He started drawing as a child, with a graphite pencil, then he would dip matches in water to get colour, and he remembers well the moment when his aunt from Novi Sad sent him a box of wooden crayons. For his fifth birthday he received wax crayons, which he loved so much that he remained connected to oil pastels all his life. His parents enrolled him in electrical engineering, because, naturally, they wanted a secure occupation for their son, who would spend all day sketching and painting.

“When they saw how fascinated I was by painting, they were afraid that I had no future ahead of me. My father was particularly scared, so he would say to me “You’ll end up somewhere as a beggar beside the road, under a bridge, you can’t make a living from art. They enrolled me in electrical engineering. I spent a day short of three months there as an extramural student. I went to all the lectures, to all the colloquia, but I didn’t pass anything. I dropped out and carried on painting. It was the most beautiful year of my life, all I did was paint.”

Due to the great age difference between them, Dragoljub’s older brother was a great authority for him, which led to him having a decisive influence on him enrolling in architecture. He told him that he would be able to draw there, but also that architects have good prospects everywhere in the world, and so it turned out. He passed the entrance exam with ease, topping the list with the most points, and completed his studies in Belgrade. He spent a short time working at one company, but quickly grew bored and chose to enrol in postgraduate studies in photography at the Faculty of Applied Arts. A positive consequence of the time he spent working at that company was his meeting Dobrila, a lawyer who became his girlfriend and then his wife, giving birth to his two sons and leaving her job to accompany her husband in his final choice – to be an artistic photographer or, more precisely, a painter with a camera. He has long been a master of photography, one of the best in this region.

“I often consider how lucky I’ve been to have done, and to still do, the work that I love. And when it comes to photography, I loved doing photo reportage features the most. As interesting, unusual and expressive as possible. Reportage works include everything – events, comprehensives, portraits, relationships between characters etc. I wasn’t particularly interested in portraits individually, unless there was a specific order, such as when I photographed then President of Serbia Slobodan Milošević for the front page of Time.”

When Milošević lit a cigar during the interview for Time, Dragoljub started capturing the moment with his camera, but Milošević asked him not to record it, which the photographer respected. He was prevented from photographing President Vojislav Koštunica as he was leaving a church by the head of the president’s cabinet, Ljiljana Nedeljković. However, he had no problems with Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić.

“Zoran Đinđić understood photography and its significance, while Milošević and Koštunica didn’t. For a year while Vojislav Koštunica was president, I worked officially as his photographer, with the idea of creating a photo monograph about the first democratically elected president of our country. I reviewed many monographs on world presidents, such as those on Kennedy and De Gaulle, and I had the idea to show the life of our president, and not just to take pictures of him shaking hands with officials. I was supposed to be his shadow, who would record history with my shots. However, that was impossible and I left that position.

“Actually, as far back as I can remember, I’ve been an opponent of every undemocratic government. That’s because not a single government has fulfilled its promises. And I believe that the only task of the government is to be at the service of the citizens; for there to be people in power who do their job like you and me, and not ridicule the citizens. The police should protect the citizens, and as far back as I can remember, the police have been protecting the government. I’ve never been a member of any political party, because I consider them to be party sects. And I think that all those who join a party, especially a party that is in power in any country at that time, do so exclusively out of greed. I didn’t want to vote during the time of communist Yugoslavia, because I thought that was a complete waste of time, due to the one-party system. I think that today we’re, unfortunately, returning to a one-party system, and one that’s a long way from democracy.”

The 1990s were unpleasant for life, wars brought misfortune to most of the former country called Yugoslavia; powerful political, military and paramilitary people decided what could be published and what couldn’t. In this country it was difficult to take photographs illustrating the truth about events related to life.

I believe that the only task of the government is to be at the service of the citizens; for there to be people in power who do their job like you and me, and not ridicule the citizens

“Photojournalists always face that. I remember the moment I entered Vukovar, on the first day that the army entered that city. I was fortunate that a friend of mine knew the editor of The Front, who put me in a jeep and, along with a TV cameraman, drove us to that city. So I was practically at the centre of events. I was left stunned when I entered one yard and saw hundreds of dead bodies. They were corpses from the hospital that had been dumped there. And I started taking photos. I was looking for the best light, the most unusual angle, in order to get the best possible photos. I didn’t feel anything while I was doing that. It was as if they weren’t people, dead people who had various injuries that caused them to have been lying in the hospital. I felt like I was part of the camera. But when I came home, when I developed the film and looked at them, I felt so sick that I couldn’t stop vomiting. While I was working I’d felt like I was shooting some scenes from a film, and only in the developed photos did I see what I’d been looking at. It was an incredibly tormenting feeling.”

Zamurović’s photographs are created primarily as a result of his artistic competence, which requires a good eye and clarity of thought. While he was active and earning money, he always bought the latest model of camera that appeared on the market. He worked for famous French agency GAMMA, which sent his photos to all parts of the world, and back then he was well paid for that. He always had a few cameras. He got rid of old models by giving them away or selling them:

“There’s an interesting story of how I switched from Nikon to Canon. I used Nikon from the beginning, but it just so happened that, at one point, Canon produced a lens that Nikon didn’t have, and which was very important for capturing various events, such as demonstrations and riots of all kinds, but also warfare. It created a 20-35mm f 2.8 wide-angle zoom that enabled photojournalists to capture wide and super-wide scenes from the same location. I was on some battlefield in Bosnia when a soldier approached me and said that he had the same device as mine, and he offered to sell it to me. I declined, but after half an hour he returned and brought the camera. He’d brought a new version of the latest Canon, and not a Nikon, and it was that Canon with the wide-angle zoom. I was amazed, wondering where’ he’d got it from.

When I opened the back, where the film is placed, there was a plastic covering confirming that it was a completely new device that hadn’t yet been used. At that time, that device cost 7-8000 Deutschmarks, and he asked me for 200 marks to buy it from him! I only had a hundred marks with me at the time, but there was a journalist from Time Magazine, with whom I was doing a report, and he lent me the other 100 marks, which I gave back to him when we returned to Belgrade. So I bought that famous Canon and for the next year I worked in parallel – using the telephoto lens with a Nikon and the wide-angle zoom with that Canon. When that became too complicated for me, I went to Vienna, where cameras could then be easily sold in specialised shops. I took all my Nikon cameras – I had three cameras and seven or eight lenses – and told them that I wanted to sell them all to buy a Canon. And so I abandoned Nikon and have been using Canon ever since.”

I remember the moment I entered Vukovar, on the first day that the army entered that city. I was left stunned when I entered one yard and saw hundreds of dead bodies. They were corpses from the hospital that had been dumped there

Dragoljub also uses various aids that are essential for creating wonderful monographs, including the ones about Serbia that are the best advertisement for the whole world to come to Serbia and get acquainted with its beauty. He has a one-seater balloon, which he sits in to climb above the object he wants to shoot. It’s light and mobile, and when he lands somewhere it’s easy to take off again and continue on, which is impossible with a basket. That balloon with its seat is so precise that he once flew over the Danube with it, dangling his feet in the river. Of course, planes, helicopters and other flying machines are a given.

Part of the professional engagements of CorD’s interlocutor includes recording riots and demonstrations in Belgrade, of which there were many in the 1990s, but also in recent years.

“That’s a shoot like any other. The most important thing for me is to distance myself a little from other colleagues, to find a place where the angle is best, and to depict an event that can often be dramatic. I don’t like having other photojournalists beside me at all. The essence of this stance is that I want to have exclusive photos that others don’t have.”

As a member of the Applied Arts and Designers Association of Serbia (ULUPUDS), he gained the status of a Distinguished Artist. However, of all the acknowledgements and awards he’s received, what means the most to him personally are his photos that have been published in the world’s most famous magazine, Life. As a young man, Dragoljub imagined, or rather dreamt, that his photography would be published in Life. He recalls that dream in detail.

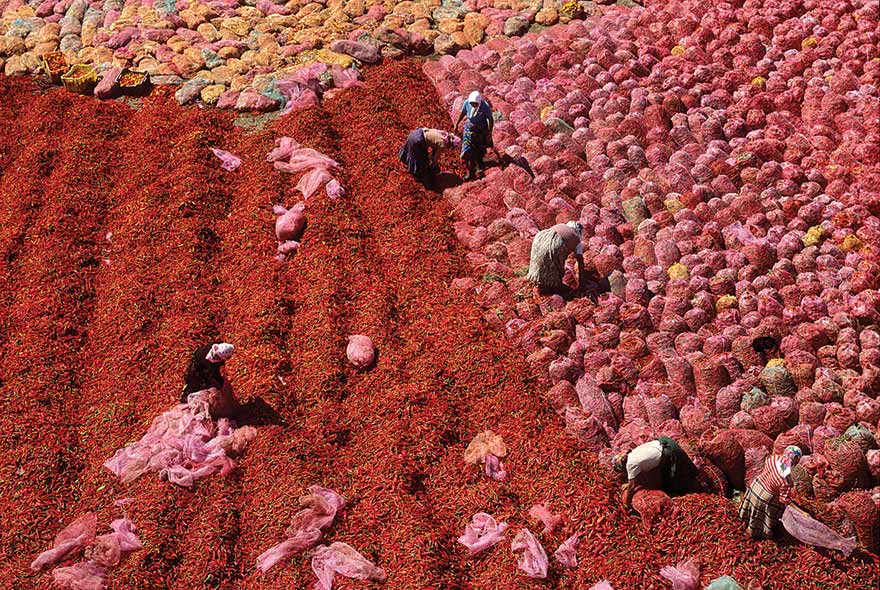

“Life arrives. I see the cover page, touch that fantastic paper, look at that print, open the magazine and see my photograph. I dreamt that dream countless times until 1991, when a friend from America brought me the latest issue of Life magazine, which could no longer be bought here at that time. I opened Life, and inside was my photo! And it was published in the spot where the best photos are published, and not as an illustration for some text. The picture showed a yard in Strumica covered with red bell peppers and a group of gypsies packing them in sacks. I’d climbed up some transmission line to get the best possible shot.

“At first I thought, ‘look, that photo’s the same as mine. And then I read ‘Art Zamur/Gamma, Strumica, pepper harvest’. And I realised it was mine after all! That was one of many of my photos that GAMMA distributed around the world on a daily basis. And I’d done an entire series of slides for a monograph about Macedonia that would have been published by the then Yugoslav Review if Yugoslavia hadn’t collapsed. It was ordered from me by Nebojša Bato Tomašević, the top man of the Review at the time. To be completely precise, the moment I saw my photo in Life I felt like all my dreams had come true. And since then I’ve never dreamt that dream again.”

He has another dream, a realised dream, which represents the basis of his life, and that is the dream of Dobrila and their sons. When he was fifteen years old he dreamt that he would have a close associate in his work as a photographer, but he didn’t think that would be his wife. She followed him in his work and helped him from the very first moment. They shot portraits of children in all Belgrade nursery schools so that they could buy the best cameras. Over thirty years of work, they have shot pictures of almost a million children.

He claims that Dobrila is a better photographer than him, and that he is more of a painter with a camera. They invested everything they earned in travelling and recording and printing photo monographs. And they also raised their sons, Nikola and Marko. Nikola, the elder son, graduated in architecture, but alongside that also deals with computer art, while Marko graduated in cultural management and photography is his main activity. He recently made an interesting book about Mačva, had a solo exhibition at Singidunum and is currently seeking a publisher. Their father is proud of them because they chose their own path, just like he did.