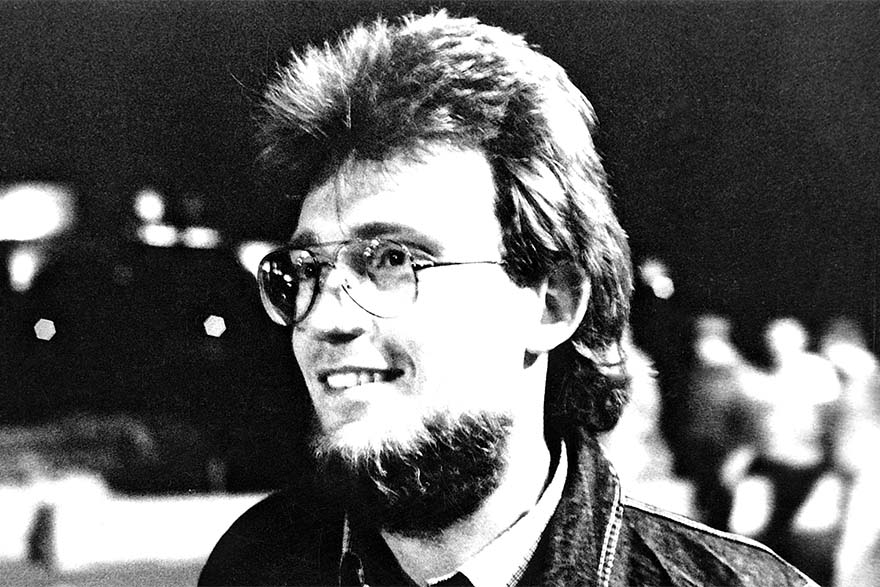

A professor of the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad, a writer and Serbian literary scholar, Dragan Stanić Ph.D. is one of the few presidents of Matica to have led this oldest shrine to Serbian literature, culture and science for a third consecutive term. For the 196th year of this institution’s existence, professor Dragan Stanić is its 27th president. His election as this institution’s top man was expected and welcomed by all cultural workers in Serbia, with only he himself considering that there are perhaps more worthy figures. Živan Milisavac, Čedomir Popov, Božidar Kovaček et al. Connoisseurs weighed up the situation well, noting that – at the time of the election for such an important position – there was no man better suited for the job than professor Stanić.

Unbeknownst to himself, Stanić seems to have been inadvertently preparing for the responsibility of leading the Serbian people’s most important institution for years. Matica Srpska is like his second home: he first served as its secretary, then as editor of its chronicle Letopis, representing Serbia’s oldest periodical, which has been published in continuity for almost two centuries, and then took on the role of chairman of the Editorial Board of the Serbian Encyclopaedia, only to finally be elected president of Matica Srpska in 2012.

Professor Stanić is also a poet, who is better known in literary circles under the pseudonym Ivan Negrišorac. His many obligations – first and foremost as president of Matica – don’t prevent him from being a literary scholar, but they do stop him from dedicating more of his time to other literary genres – novels, dramas, essays. If his health serves him, and provided he has enough creative energy, he says that he will make up for that in the future. He is simultaneously also a regular professor at the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad, where he lectures on literary theory.

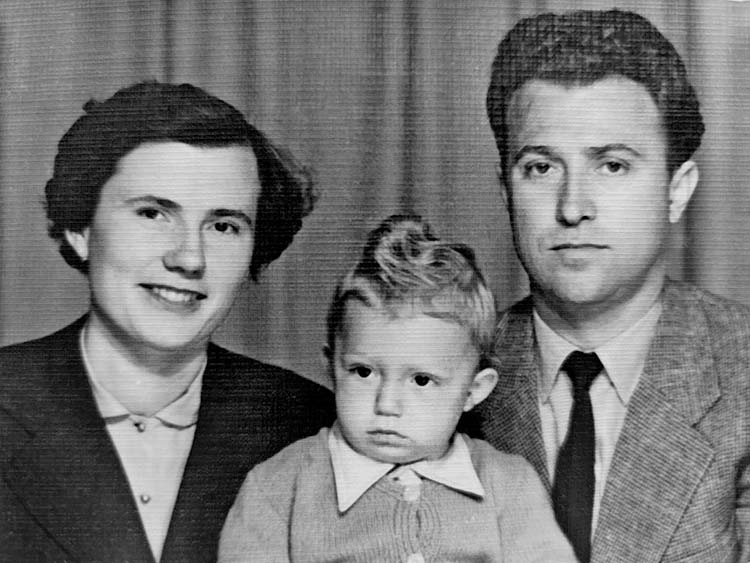

“I remember my childhood as a carefree time, during which I gained those first experiences that are in the sign of childish innocence and purity. I grew up in Sirig, a village close to Novi Sad, and that rural childhood is something that I value today as the most beautiful period of my life. In that pleasantly tame environment, but also at my grandparents’ place, where I spent my summers, I befriended animals and plants, nature, which I experience as a beautiful, almost poetic blessing. I wasn’t a stranger to the city either, on the contrary, I often visited Novi Sad with my mother Stamena and father Mile, to visit my uncle Ivan. When my father, who worked in Novi Sad, received a flat, we lived between the village and the city, until we quickly relocated entirely to the city.”

I experienced a complete turnaround when I realised that what I’d been taught, which was an atheistic image of the world, had no basis in reality, or rather that there is a different image of the world that is much more multifaceted and offers a much richer view of everything that comes after a person’s death. And that’s an image of the world that, alongside science, leaves a much broader space that is observed through the lens of poetry, religion and philosophy

And to this very day that hasn’t changed much. He still lives in the city, while yearning to be in the countryside. He is at his happiest when he’s at his holiday home in Čortanovci, on Fruška Gora, where – just like in his childhood – he befriends nature. Though, admittedly, there are none of those animals that he had at his relatives’ rural place, with cats, cows, sheep…

“I loved animals and took care of them. That love was mutual. When I would visit my grandparents during the summer break from school, I would also take on certain responsibilities around them. They entrusted me with caring for sheep and cattle, with feeding and watering the horses… I first rode one when I was ten years old, pulling another horse by the reins to the well to drink. When I look back today, I know that I had a beautiful childhood.”

Stanić’s parents were highly educated people (geography professor mother and philosophy professor father) and they had a large family library. His father was a particularly passionate buyer and reader of books, and that love didn’t bypass his son either. His mother still reads novels every day, at the age of 90. He grew and developed intellectually alongside his parents, while the other side of his upbringing was his enjoyment of nature and an everyday life that showed him all the values of the Serbian people and culture. His father’s region of Dragačevo and his mother’s homeland of Šumadija, along with Bačka, where he grew up, helped him to develop an understanding for the many differences of Serbian culture, but also for how these differences contain numerous underlying similarities. He discovered how the rural way of life enables people to live from what they themselves produce, which delighted him. In the early 1960s, in the Stanić family home in the Dragačevo village of Negrišori, the only things they bought were gas for lamps, salt and sugar. They didn’t even use much sugar, as they had their own apiary and honey. They produced everything else themselves.

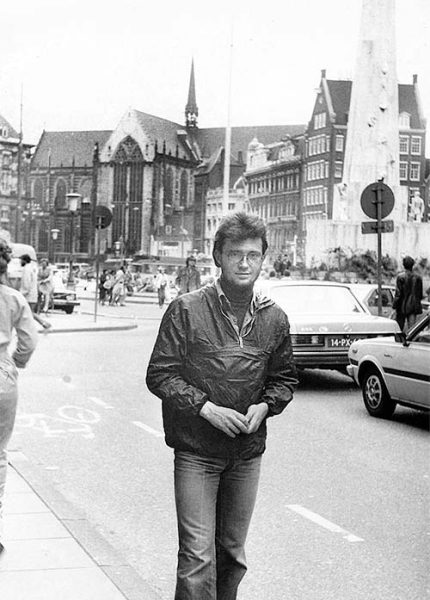

His secondary school years were a time of enjoying the beauty of his youth and his school days at the Svetozar Marković High School, where he completed his schooling. Surrounded by great teachers, he socialised while walking around the famous “Novi Sad strafta”, where all the students tended to head after classes, staying until 9:30pm and only then returning home. He lived just like his peers.

I see some fated connection with Matica, which awakens within me a special kind of metaphysical, mystical responsibility on behalf of all these people whose portraits I look at every day and feel as though I’m answerable to all these great men for my actions

“It was then that my life began to get complicated. A split suddenly appeared in my experience of the worldview I’d held. This had actually first occurred to me back in primary school, sometime during the fourth year, but back then such phenomena were less frequent, and less intense. I experienced serious existential crises, which were primarily a consequence of me being confronted by the phenomenon of death. That was a major metaphysical problem for me, which I set about resolving, with great difficulty. That period lasted until somewhere around the end of my twenties, or more precisely until the age of 28. I experienced a complete turnaround when I realised that what I’d been taught, which was an atheistic image of the world, had no basis in reality, or rather that there is a different image of the world that is much more multifaceted and offers a much richer view of everything that comes after a person’s death. And that’s an image of the world that, alongside science, leaves a much broader space that is observed through the lens of poetry, religion and philosophy.”

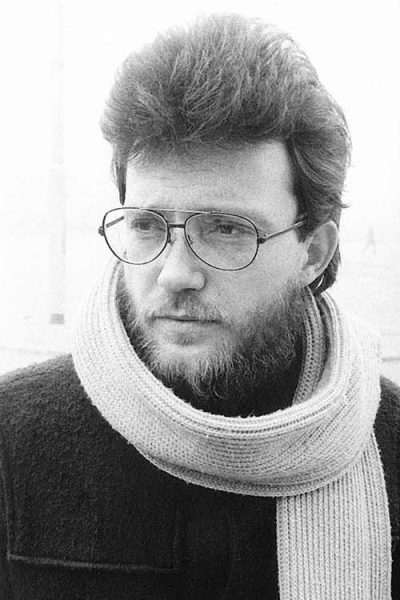

As a then young man, he began adopting different views on life, the world, people… He decided to continue heading in that direction, and it became his own personal path. He had to deal with it himself, because nothing in the education system encouraged him to do so. He recalls with particular sentimentality some intellectuals who’d had an ear for such topics, like Nikola Milošević, Vladeta Jerotić and an entire array of people who’d raised such questions at the time Marxism was imposed on the people. He spotted all the limitations of the Marxist worldview, while his discoveries of other kinds of knowledge, such as Indian – not only through reading, but also through spiritual practice – opened him up to new horizons. With his discovery of Christian Orthodoxy in the mid ’80s, peace and serenity returned to his life. Also contributing to this were the country’s most spiritual figures, who marked our entire intellectual life, firstly our great hieromonks, later bishops and metropolitans – Bishop Irinej, the late Metropolitan Amfilohije Radović, Bishop Atanasije and a series of other spiritual leaders, among whom the most important for him was Father Tadej Vitovnički.

“I was fortunate enough to meet Father Tadej during the moment of one of my mental breakdowns, and that’s how it came about that I returned to the path of my ancestors, though greatly delayed. My father was a selfproclaimed atheist, a communist, stubborn and consistent in his views. He didn’t have understanding or answers to the questions troubling me. I found those answers in the books I read and in conversations with spiritual people. I hope I will one day convert this drama that I endured in my youth into a literary testimony that will show the seriousness of all the problems I encountered.”

Alongside the many projects being worked on at Matica, professor Stanić attaches great importance to everything related to the Serbian language – orthography, normative grammar, the MS Single Volume Dictionary. All these books have also received their versions in the Ijekavian dialect

He believes deeply that crucial things like love and the search for the meaning of one’s personal existence are eternal preoccupations of man. Material things are undoubtedly necessary for life, but life’s higher meaning manifests on another plane. In these times in which we’re living, when talk of the material is constantly imposed on us, there will always be those striving towards life at that higher level. He’s of the opinion that everyone endures similar trials and tribulations at some point in their lives, but he hopes that today’s youth and some future generations will be able to handle that successfully.

Professor Stanić is today a self-aware man, a man greatly devoted to Matica Srpska and everything this oldest independent, non-profit, non-governmental, cultural-scientific Serbian national institution does and fights for. And he has always had an innate sense of responsibility and justification for everything he does.

“I experience my duty as president of MS as a great honour, even though I’ve always been convinced that I’m not worthy; that there are older, more deserving people… I have a special relationship of responsibility towards this institution, with deep awareness of the noble functions it takes charge of. Some magical connection exists between me and Matica. When I recalled the past, in my poetic imagination, it appeared in its own way. My uncle lived across the street from Matica and the imposing Matica building was the first thing I saw in Novi Sad when I was brought there as a baby. When I would later come to my uncle’s house, my concept of that building was as a place where intelligent people gather, where a huge library exists… I couldn’t comprehend all those facts in a tangible and meaningful way as a boy, but I only know that I always felt a great internal respect.”

Who would have thought that today’s Matica president spent the early 1960s playing football with his cousins Mićo and Vojkan in front of the building where he would one day serve as president? Cars rarely drove by back then, and children kicked the ball in Matica Srpska Street without a care in the world. Later, in 1995, when he was appointed Matica secretary, he was haunted by images of those bygone days. When he would circle the institution and head down to the building’s basement, looking through the windows, to both the left and right of the central entrance, he would recall the image of playing carefree as a child… As though in a trance, he would again see himself, as a boy, playing football in front of the building, with the glazed basement windows, protected by wire netting, serving as the goals. As the poet Ivan Negrišorac, he wrote a poem about that secretary who descends to the basement and observes his childhood from a distant yet familiar perspective.

“I see some fated connection with Matica, which awakens within me a special kind of metaphysical, mystical responsibility on behalf of all these people whose portraits I look at every day and feel as though I’m answerable to all these great men for my actions. To mark the occasion celebrating the 196th anniversary of Matica, His Holiness Patriarch Porfirije noted that “the life and work of Matica is intertwined with the life and work of our Church”. Testifying to this claim is the fact that, during the 19th century, Bishop of Buda and Bačka Platon Atanacković served two terms as the president of Matica Srpska, but other senior figures in our church have also been active in Matica.

“Since its very inception, Matica nurtured the spirit of Serbian Christian Orthodox values and the way of life that derived entirely from all of that, until the post-World War II period, when greater importance was attached to some other values. My predecessors worked to change that situation. Back when Boško Petrović served as president of Matica, and bishop Irinej became the Bishop of Bačka, a symbiosis was again formed between Matica and the Church. That spiritually enriches and strengthens us, so I couldn’t imagine Matica functioning in any other way than continuing along the path we’ve been living, for more than three decades, in full Christian communion and acting in complete rapport with our Church.”

Professor Stanić is a man who loves his own people and respects others. He can’t imagine the history of Serbia without Kosovo. It’s clear to him that Kosovo could, in a political sense, be displaced from the political framework of the state controlled by the Serbian people, and that this can only be done by force. In a spiritual sense, for him the tradition of Kosovo is fully part of the very foundation of our being

It was predestined that Stanić would become a writer and poet. He spent eight years as editor of the Letopis chronicle of Matica Srpska, a key asset in Matica’s existence and a periodical that still today forms the basis for the development of Serbian literary life and other disciplines. Preserving Letopis, both now and in the future, represents one of the most important missions still to be faced by Matica. The very survival of Letopis was under threat during one period, but the danger has since abated and Matica is happily preparing for a great anniversary: commemorating two centuries of the existence of this chronicle that represents the only periodical in the world of literary magazines that has been published in continuity for such a long period.

Alongside the many projects being worked on at Matica, professor Stanić attaches great importance to everything related to the Serbian language – orthography, normative grammar, the MS Single Volume Dictionary. All these books have also received their versions in the Ijekavian dialect. This serves as a clear declaration that the lands of the Serbian language encompass the areas covered by both the Ekavian and Ijekavian dialects. There are some unreasonable people who think that the Ijekavian dialect should be left to some other newly formed nations, or old ones with designs on usurping that which is the product of Serbian folk dialect. In this area of nurturing Serbian culture in its entirety, MS boards, like the Timișoara and Njegoševo boards, are also active, together with the newly established Krajiško, Kosovsko-Metohijska and Omladinska boards.

He also works ceaselessly to draft capital projects for our nation, first and foremost the Serbian Encyclopaedia, which will ultimately include around 18,000 pages, then the Serbian Biographical Dictionary, as well as lexicographic projects – the Multi-volume Dictionary of the Serbian Language, the Dictionary of the Slavic-Serbian Language and the Dictionary of Serbian Folk languages from the 12th to 18th centuries.

He insists that we fail to care enough about our language and script, including Cyrillic as our identifying script. Reminding us that the Cyrillic script has been persecuted in all situations when the Serbian people have also faced persecution, and that this fact in itself should serve a clear indication to help us avoid new problems, he say it’s worrisome that many people fail to see the importance of these facts, while it is evident that schools, and the education system generally, pay very little attention to language and the study of the Serbian language and literature. This results in a large number of people who don’t love their own language, and even nurture open hatred towards both it and their own culture.

Professor Stanić is a man who loves his own people and respects others. He can’t imagine the history of Serbia without Kosovo. It’s clear to him that Kosovo could, in a political sense, be displaced from the political framework of the state controlled by the Serbian people, and that this can only be done by force. In a spiritual sense, for him the tradition of Kosovo is fully part of the very foundation of our being.

Nor is he indifferent regarding the situation in Russia and Ukraine. As someone who was raised to be righteous, he claims that this conflict wouldn’t have come about if the entire process hadn’t been concocted by centres of great power that believe they have a monopoly on producing crisis hotspots around the world.

“It was the Western political elites in particular, and their corresponding services, together with the corrupt government, that began shaping Ukraine into an anti-Russian state with clear lines of hostile activity, and that could no longer be tolerated by a power like Russia. I’m not hereby justifying the military intervention itself. The West, which produced the crisis, was counting on precisely that happening. Their goal was for blood to be spilt; for two brotherly nations to become bloody enemies. I sincerely hope that relations between Russia and Ukraine will be patched up, though I’m well aware that this won’t happen easily or quickly.”

Poetry has held a very important place in his life since childhood, so it is always significant when he starts writing something important. It might be paradoxical, but whenever he started to write some poem, he felt as though something important was happening. As he matured and reached some kind of threshold of human maturity, adulthood, he increasingly realised that it is worth dedicating one’s whole life to poetry.

He has spent two decades teaching creative writing courses at the Faculty of Philosophy: professor Sava Damjanov for prose and professor Stanić for poetry. Many students have completed this “school”, where young people build themselves and become individual personalities ready to devote themselves to nurturing their internal poetic spirit.

He achieves a sense of fulfilment from working with students, but he says unequivocally that he’s dissatisfied with those students who approach their study obligations and the vocation they’ve chosen half-heartedly, with a lack of true passion and any desire to learn. There are students who don’t show sufficient desire to raise their level of knowledge and to seriously consider their own destiny: to discover why they are here, what they are doing, where they should go… That’s why he dedicates himself fully to those students who are striving and eager to learn, who read and learn constantly, broadening their own horizons. Those young people bring him joy as he watches them grow and mature…He revels in their success. Now, with the sun setting on his university career, he is nonetheless satisfied because his best students prove that it has all made sense.

Poetry has held a very important place in his life since childhood, so it is always significant when he starts writing something important. It might be paradoxical, but whenever he started to write some poem, he felt as though something important was happening. As he matured and reached some kind of threshold of human maturity, adulthood, he increasingly realised that it is worth dedicating one’s whole life to poetry

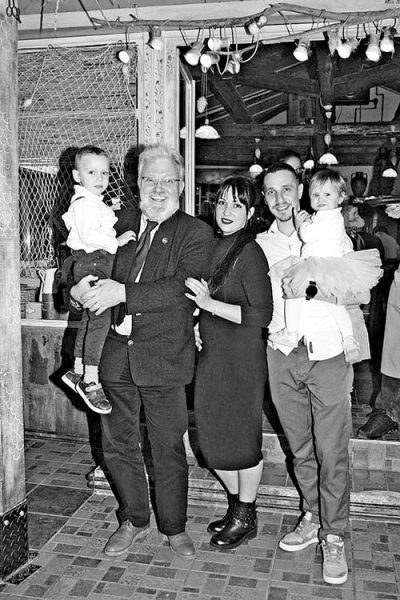

“When it comes to my literary creativity, I’ve done a lot, awards and acknowledgements haven’t been lacking, but in relation to the multitude of creative ideas, I could say, together with Branko Radičević, “your father leaves you in tatters”. Most of the time that I have at my disposal today belongs to Matica, to my daughter Isidora and her family, and that all has its price. But I somehow still believe in the time ahead of me. It’s not yet time for settling accounts; there will be new articles and new books, everything that has comprised my literary world. I have always written with all my heart. All periods of writing are dear to me, I’m honest with the pen. I’ve received awards and accolades, but after receiving an award I’ve always tried to hold myself and others to account: why that accolade; did I deserve it? Who’s on the jury is important to me, whether they’re people with honest and fair judgement. And it’s just as important for me to know whose name the award bears.”

The fact that he’s excessively busy and dedicated means that he almost abandoned the joys of everyday life, above all spending time with his family, his grandchildren… Despite his obligations and interests, he tries to dedicate every free moment to his nearest and dearest. Unfortunately, his wife Mirjana has passed away, so he now fills the time he spent with her in other ways: by working or spending time with his family or friends.

“There’s never enough time, and recollections of loss are ever more intense and painful. I miss my wife tremendously, but to my joy there are also happy moments when she shows me that she’s still somewhere around us. And only poetry can preserve and unify all those experiences.”

By Zorica Todorović Mirković; Photography: Branislav Lučić