A childhood dream about the big wide world, an islander’s dream from Ugljan in the Adriatic: Budimir Leko Lončar realised his dream in decades of diplomatic work, taking every step and challenge since 1949, serving as SFRY’s last minister for foreign affairs, to name but one of his public offices. Today, at the age of 93, he is still committed to some uncompleted missions

Talking about his marathon of life, Budimir Lončar starts from the unforgettable moments in his childhood. “The greatest event was when a big ship passed by, especially if it anchored by our village. We used to feel that the world had paid us a visit and we were always in awe, longing to be taken to faraway shores. This is something that’s stayed with me forever.

“When I finished primary school, my parents were in a dilemma: should I continue my education – which wasn’t easy because of hard financial times and the isolation of the island. Zadar was the nearest place, only two nautical miles away and visible from my native Preko, but it was under Italian occupation, having fallen under their rule after World War I.

Of course, no one would even dream of sending their child to school there because it meant giving them over to another culture, another nation. My father’s two brothers were living in America and he wanted to send me there. My mother preferred me to stay and go to school, and this prevailed with the support of the elder brothers. They sent me to Zagreb.

And how did I go into diplomacy and set off into the world?

World War II definitely played a crucial role. It was a fight for freedom, without defined ideological goals.

Though the fight was lead by the Communist Party, we, scores of young people who joined it, were just against the occupier, without prejudice. All of this turned us into thinkers and there were two things that ran in parallel: an interest in the world and a childhood longing.

My later initiation as a diplomat happened more by chance, at the time when Yugoslavia was under pressure from the USSR. This was in 1949 when the international position of the country and its foreign policy needed to be defined. At the time, Yugoslav diplomacy recruited new, ‘tested’ but very capable people. I saw diplomacy as a special challenge and privilege, I was aware that I was treading uncharted territory and that uncertainties were ahead of me.

Finally, in 1987, I became the first minister for foreign affairs with a professional background. The position was usually occupied by people with a background in politics. Of course, I’d never dreamt that I would become head of diplomacy but I did believe that I would be a successful diplomat, an ambassador at best.”

At the time, Yugoslavia was presiding over the Security Council and Aleš Bebler was our Head of Mission. I was sitting in the back row, more to hear and learn than to be of some use. He was brilliant. His competence was admired by everyone, it scared me. He addressed the French in French, the English in English, the Russians in Russian, the Spanish in Spanish

Mr Lončar was ambassador five times.

“My first diplomatic post was New York”, he continues, with the story about his early days. “I was part of the mission to the United Nations. It was a stroke of luck (I was supposed to go to Paris) that they published a competition for the post that year, in 1949. Since I had an uncle there and like any islander an affinity towards America, I was pretty self-confident. To me, New York seemed more attractive, easier than Paris (and I’d never been to either city).

I arrived there when the Korean war broke out. It was dramatic. At the time, Yugoslavia was presiding over the Security Council and Aleš Bebler was our Head of Mission. I was present at that meeting. Of course, I was sitting in the back row, more to hear and learn than to be of some use. Bebler was brilliant. His competence was admired by everyone, it scared me. He addressed the French in French, the English in English, the Russians in Russian, the Spanish in Spanish. When the meeting was over, I was so proud of the role of my country and the superiority of our ambassador. But I didn’t sleep all night. I was wondering how I was going to cope in that environment.

I’d just started learning English, I’d just started learning about the world, while these people were solving its most difficult problems. How could I go back home? But then I felt the awakening of partisan courage, determination and obstinacy: I must stay here, this is a huge privilege for me.

“These were also the times when Yugoslavia was establishing its international position. We were to earn the trust of the West, especially of the United States, and establish closer relations not only with America but also with the rest of the world. It wasn’t easy because this was also the time of the American McCarthyism and witch hunt. I was lucky that Yugoslav diplomacy had two great men who had fought in the Spanish Civil war, two experienced men of the world: Aleš Bebler in New York and Vladimir Popović in Washington. Looking back, I can really say that good fortune was with me at that time.

“Emboldened by my inexperience, strong patriotism and post-war euphoria, I socialised with very important people. So many of them helped me in those early days and I remember them with gratitude and respect to this day. General Ellery C. Huntington helped me a lot, he was a member of the OSS, the American intelligence service and Head of US Mission during WW2 with Tito. He introduced me to William J. Donovan, Head of the OSS. Even my superiors were amazed that I knew these men personally.

Professor Philip E. Moseley meant a lot to me too. He was from Columbia University, a Slavist especially interested in Yugoslavia, a Chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations. Professor Moseley was one of the highly respected experts on the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Franklin Clark Fry, President of the United Lutheran Church for America and then Pastor, who later became President of The Lutheran World Federation, was a man who opened many doors for me, made my work easier and boosted my self-confidence.

All this was a valuable experience for me, a great challenge and a test. I still think that my beginnings in New York were tough, but crucial for my professional, human, intellectual and cultural growth. Despite my initial trepidations, my success surpassed my expectations.”

Leko remembers another “important moment in life”. “Thanks to Koča Popović, who had faith in me and with whom I’d spent eight and a half years (his parting present was a photograph with a dedication that read: From a tormented tormentor), I learnt a lot about the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement and the articulation of its policy. And I’ve been true to it all my life. Even when I was holding other posts, I was always engrossed by it.

I must say that I have made many friendships and received many a recognition through the NAM, which continues to function, although with some oscillations and all its weaknesses. I have invested a lot of my energy and knowledge in it, and I’m proud of it. I believe that the philosophy of active peaceful coexistence is as relevant today as it was decades ago.”

Mr Lončar talks in detail about the internationalisation of the Yugoslav crisis, a challenge that, as he puts it, “was the most painful one” for him.

“I was a minister when I found myself in a situation where I had to think how to use our international relations to de-escalate a constitutional and political crisis, how to turn our massive foreign-policy capital into support and influence from as many countries as possible and, if necessary, their intervention to prevent what, sadly, did happen – a bloody conflict. It was clear that Yugoslavia couldn’t survive as it was. As a one-party yet multinational country, lagging behind its own democratic and foreign-policy commitments, it was outdated.

Tito was certainly the leading foreign policy strategist. But this was a policy that brought up many extraordinary people, developed its own merits and, one can say, its particularly recognisable style. The inventive people who led the way were Vlatko Velebit, Aleš Bebler, Veljko Mićunvić, Leo Mates, Mišo Pavićević, Josip Đerđa, Vladimir Popović, Mladen Iveković, Ivo Vejvoda

“I must say that the internationalisation of the crisis was the most important and most difficult mission and task I’ve ever had. In a way, the capital that Yugoslavia had acquired gave it the right to ask the world to help,” he continues. “I believed that we should turn to the EU. Despite little enthusiasm in the EU and even less among the Yugoslav leadership, and thanks to my friend, the late French foreign minister Claude Cheysson who was then in charge of EU enlargement, and to Jacques Delors, President of the European Commission, I made a bold move and succeeded in having our association accepted as an orientation for future membership.

This happened after twenty years of relations between Yugoslavia and a united Europe. This logical move was followed by another one: against the stance of the country’s Presidency, I practically imposed the second presidency of the Non-Aligned Movement on Yugoslavia. They were seemingly contradictory moves. But with the need to build a new order and a nonaligned policy, we had to spur our evolution and affirmation. Minister Hans Dietrich Genscher, and in particular our French colleague Cheysson, suggested that the Non-Aligned Movement should get more involved in the global processes that came into being when the Cold War ended and that it would be best if we took the initiative, i.e. bring the NAM’s presidency to Belgrade. And this was supposed to help peaceful resolution of the Yugoslav crisis. These two initiatives were my greatest diplomatic achievements. Sadly, neither of them bore fruit. So it was a Pyrrhic victory that turned into a great, the greatest failure.”

Leko then concludes, “The war broke out in Yugoslavia, although this internationalisation did affect some processes and eventually the end of the conflict, it wasn’t in time and it didn’t prevent the war. Yugoslavia had reached a stage where it had to be redefined, as I said at the meeting of the Security Council that I’d also initiated so that the legitimacy of international intervention was recognised by the most important body of the United Nations and under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter, while everybody kept asking how a country that was so different from other East European countries had suddenly found itself in such a predicament.

What happened to us was that the ruling party, the ruling structure, was not capable of carrying out accelerated democratisation, which meant pluralism and market orientation. It was happening, but it wasn’t decisive enough. It was a precondition for re-ordering the federation, which was effectively a confederation under the 1974 constitution, and the republics were the ones that held sovereignty.

Naturally, Milošević’s nationalistic politics tried to use the Yugoslav National Army to break up not only the federation’s constitutional foundations but also the foundations that were established under AVNOJ, and to take advantage of big historic upheavals in Europe and worldwide to redesign Yugoslavia under a Unitarian hat. How things then developed in the wild frenzy of the lowest of nationalist forces is only too well-known.”

Hearing this open exposé, we wanted to know who in the former Yugoslav diplomacy Mr Lončar particularly held in high regard.

– “This is at the same time an easy and a difficult question. Different generations worked in different times. Tito was certainly the leading foreign policy strategist. But this was a policy that brought up many extraordinary people, developed its own merits and, one can say, its particularly recognisable style. The inventive people who led the way were Vlatko Velebit, Aleš Bebler, Veljko Mićunvić, Leo Mates, Mišo Pavićević, Josip Đerđa, Vladimir Popović, Mladen Iveković, Ivo Vejvoda.

My generation inherited and learnt a lot from them. Our predecessors were people of the world by education, knowledge and experience, courage and personal integrity. For instance, Vlatko Velebit’s mission and his talks with Churchill in 1943, when as a representative of the National Liberation Movement he impressed his British counterparts, is well-known.

Koča Popović’s contribution to the development of Yugoslav diplomacy was the greatest. He was head of Yugoslav diplomacy for thirteen years. He was definitely the one who left the strongest impression on me and he remains the greatest authority to date.

What does he say about his predecessors, the ministers?

– “Koča Popović’s contribution to the development of Yugoslav diplomacy was the greatest. He was head of Yugoslav diplomacy for thirteen years. He was definitely the one who left the strongest impression on me and he remains the greatest authority to date. He could see the advantages and disadvantages of any concept. As a great intellectual, he was always tormented by doubt and self-criticism. This would sometimes hinder his efficiency. But this was his virtue, worthy of respect. Many considered him a cynic but he was really the hardest on himself.

Marko Nikezić used to impress me with his ability to find simple solutions to difficult, complicated problems through light communication, subtly conducted talks, solid opinions and consistency.

Mirko Tepavac leads the ministry for a relatively short time. He played an important part and left a big legacy. He was a man of great integrity, strong resolution and high ethics. Here’s an example: When Brezhnev visited the country in September 1971 there was some tension in relations with the USSR, and Tepavac and Gromyko ended up in disagreement over the final document. Brezhnev complained to Tito about Tepavac’s opposition to the statement that socialism was particularly important for mutual relations.

Tepavac was adamant that Yugoslavia’s fundamental position was that international relations, including those with the USSR, should be de-ideologised, as an ideology was a hindrance to international relations. I remember that even on the Brijuni Islands in 1972, when the international situation and the position of Yugoslavia were discussed and Kardelj criticised the position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as ‘lacking an ideological component and emphasising the superiority of political pluralism and the market economy’, Tepavac replied that the value of the analysis was in its non-ideological approach.

Miloš Minić became a foreign minister after the fall of the Serbian liberals. He had no diplomatic experience but he had a good reputation on the political scene. He was well-educated, refined and Tito’s loyal acolyte. Political leaders at the time and ambitious staff in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wanted to oust those close to Marko Nikezić, Mirko Tepavac and Koča Popović. Minić strongly opposed them. He didn’t allow a purge.”

And from the big wide world, who is on your list?

– “First and foremost, Willy Brandt, as a moral and political pillar, with his historic contribution to Germany’s facing its demons from the past and with his vision of how to end the Cold War, how to turn Germany, the object of the Cold War, into an actor in the detente and unification of Europe. I was impressed by Jawaharlal Nehru and his views on how to make yesterday’s colonial powers an integral part of the global community and how to heal the painful wounds and overcome the legacy of the colonial past.

Indira Gandhi left a strong impression on me with her extraordinary view that India, as the greatest democracy among the Non-Aligned countries, should unobtrusively yet efficiently develop a sense of belonging to the NAM in both large and small countries equally, without making the latter feel subordinate.

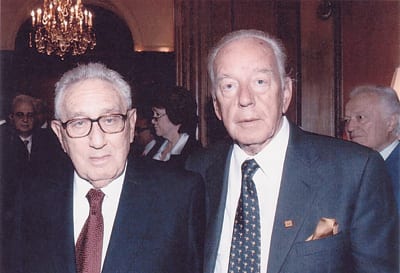

In his own way and for some other reasons Richard Nixon is also on my list. He was a typical, thoroughbred follower of realpolitik. What Henry Kissinger developed and implemented was in essence Nixon’s idea too. He started the dialogue with the USSR about arms control, especially nuclear arms control. His relationship with China remains important up to the present day. After he’d resigned, I met him on several occasions and I always saw him as a human being who naturally represented the interests of a great capitalist and imperialist country but who also had a sense of the world that was changing and was at the same time interdependent.

I was also impressed by Mikhail Gorbachev, whose credits are historic although his visions didn’t come true. I had interesting, enriching conversations with him, although I had a feeling that he took some aspects of Western politics too lightly. He failed to understand that the politics were not determined only by governments or country leaders but that there were the so-called ‘constants’ too, such as the military, intelligence and big corporations with their influential lobbies.”

Mr Lončar mentions many others. He has fond memories of his French colleague Claude Cheysson, “whose best man I was, albeit at his third wedding”, and of his German colleague Hans Friedrich Genscher. “Herbert Wehner once asked me, ‘What do you think, how is this meaty man with big ears going to handle foreign affairs? He’s going to break all the china in our eastern politics.’ I replied, ‘I don’t know Genscher well enough, but I have a feeling that he is a man who has the ability to connect a vision with reality.’ Later, Wehner admitted, ‘Ambassador, you were right’”.

Willy Brandt was a moral and political pillar, with his historic contribution to Germany’s facing its demons from the past and with his vision of how to end the Cold War, how to turn Germany, the object of the Cold War, into an actor in the detente and unification of Europe

Has anyone disappointed him?

– “I’ve met many people whom I found interesting”, says Mr Lončar, “and I can’t say that I’ve been disappointed by any of them, because I learnt even from those who were wrong. Those who are wrong also teach us. I never thought I’d wasted my time talking to anybody. Diplomacy is the art of the possible. Of course, times and methods change. The ability to change has become increasingly important in this fast-paced and chaotic world. I was – and I’ll say it again – lucky. I made choices, but there was an element of luck as well. I surrounded myself with the most talented, most capable young diplomats whichever post I held. I gave them a chance just like I had had mine.”

And to end this or any other conversation with Budimir Lončar, a typical question: Where are you rushing off to now?

– “I’m about to leave for America. Our family is there, our sons and daughters-in-law, our five grandchildren. Only my wife Janja and I have remained here. She, as the saying goes, is the woman behind the successful man. In fact, in this time-travel – we started with New York in the past and are finishing with New York in a few days ‒ I must say that my greatest achievement is my family.

They have always been my greatest joy and biggest support. And, I’ll also be going to a meeting in South Carolina, ‘A Quarter of a Century After the Cold War: Global Realpolitik Today’. Times are hard. We have to talk and not succumb to fear and hopelessness to successfully face the threats and dangers that are lurking everywhere.”

Sailing the big wide world, that started a long time ago from the fishermen’s village of Preko, goes on.