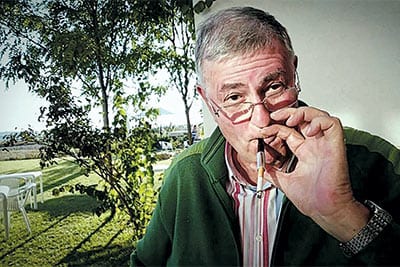

A Croat by birth, for many years he defined himself as a Yugoslav. Once famous for being a television news reporter for both Serbian and Croatian national television stations, for the last few years he’s been an irreplaceable feature of the Balkan edition of Qatar-based TV company Al Jazeera. He interviewed both Jimmy Carter and Tito, highly appreciated Alija Izetbegović, reported from the United Nations and has toured the planet. Today he is doing a major TV series in which he seeks an answer to the question: did the people of the former Yugoslavia live better while the SFRY existed or in their own countries today?

He was the biggest television star of the former Yugoslavia. He thought quickly and spoke easily, with television appearing to be a medium tailor-made for him. That’s how he has managed to survive on the small screen, with all his traits, for a full 48 years. He arrived at Croatia’s national television in 1998 and worked there until 2011. Specifically, on 23rd January that year he presented HRT’s Daily Bulletin, and the next day he turned 65 and had his working relationship cancelled, so he couldn’t even enter the building – as his computer card had already been cancelled! It was a very unpleasant feeling for him to realise in such a way that he’d entered retirement:

Despite everything, I threw a farewell party and invited friends, some brought lamb, some brought wine, there were 150 of us. Among those I invited were people from both the right and the left, including both Hloverka Novak Srzić and Zoran Šprajc – everyone was there except the members of the management team, who I didn’t invite.

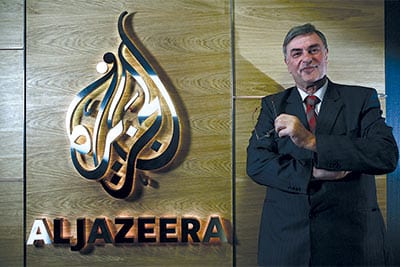

Milić was soon chosen as programme director at television company Al Jazeera, which opened its headquarters in Sarajevo. In those five years he has authored a hundred broadcasts and the series ‘Alchemy of the Balkans’, dedicated to presenting life in the former republics and provinces of the country that was called Yugoslavia:

“I had the idea of talking about the new faces of those states that emerged from one system and, with major difficulties, transitioned to another. And I think that was a realistic picture of all the misery that people went through, but we still saw the optimism with which they await the future.”

Today Goran Milić is again making a series of shows on the territory of the republics of the former country, but this time based around another idea:

“More than 20 years have passed since the col-lapse of the country, since the wars and everything that changed the borders of Yugoslavia, and now it’s possible to talk about a new trend – I’m now looking at those changes and filming, but at the same time I’m trying to get an answer to the question of whether the situation is better for the people now or whether it was better back then. I come across ordinary people, businesspeople, privateers conquering new technologies; I meet new expert professionals who have new occupations.”

The differences between the countries of the former Yugoslavia are proportionally the same as they were in 1914, prior to them being united in Yugoslavia. They may even have increased slightly

As a man with a high ethical structure, Goran’s father, Marko Milić raised his son not to fear the authorities, but also not to be rude and to respect people who are hardworking and high-quality:

“My father was ambassador to Uruguay, and I was impressed by that country. On one occasion he staged a dinner for the then elite of Uruguayan society, which left me breathless. He noticed this, and after dinner he led me to the bathroom, turned his back to me, dropped his trousers and removed his underpants. I was taken aback. Then he asked me: What do you see? I answered him: I see your arse! And he said: That’s right, an ambassador’s arse is the same as everyone’s arse. Remember that! He was infinitely honest and humane; throughout my life I never heard anyone utter a bad word about him.

” As a child, Goran travelled to various coun- tries with his father, residing wherever he served. He familiarised himself with the world early on and learned languages: he speaks French fluently and excellently, knows English well and can easily communicate in Italian and Spanish… He quickly realised that people lived much better in Western Europe than in the East, though it was only in Latin America that he lost all his illusions about the Left that had been close to him in his youth:

“Actually, it was there that I realised that the problem is in the system.

In Cuba, as a very young boy, I’d ordered fresh orange juice in a hotel, but in the city, in Havana, you couldn’t order orange juice in a tavern. Nor did Cubans have anywhere to buy oranges.

I quickly realised that this was a problem of the society, or the system, because I could un-derstand if there was no orange juice in Moscow, with its polar climate, but not why there wasn’t any in Krasnodar, which has a true Mediterranean climate. Or cigarettes. The two cheapest types of cigarettes in Yugoslavia were Drava and Ibar. They were a hundred times better than cigarettes in Cuba. And Cuba has the most expensive cigars – those that cost $20 each, but they were sold exclusively to foreigners. There were no cigarettes for the people…

“Regardless of all these discoveries, I remained loyal to the system in which I lived. I thought that Yugoslavia was okay; I accompanied President Tito on his travels to Mexico, Venezuela, Panama … to conferences of the Non-Aligned Movement, during his meeting with U.S. President Jimmy Carter. I watched him become a great world statesman and I was impressed. Of course, I don’t glorify everything he did, because there were also great crimes, such as Goli Otok (island prison for Yugoslav dissidents) and the mass retaliation at Bleiburg, for example, then confiscations and nationalisations, but one must single out his great moves, such as the Na-tional Liberation Struggle and the Non-Aligned Movement, for example.”

This journalist, who spent many years as TV Belgrade’s New York correspondent and who toured the planet, was a member of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, because such a career was unthinkable without that condition. Never-theless, he was highly desirable to the West – as he represented a reformed communist who was not dogmatic, with whom they could converse, and who was an important guest at embassies in Belgrade and in any company where important discussions were led:

“I think that communism was a respectable idea, but unimplementable, because it is … against human nature. Perhaps it would be most accurate to say that I am today a man without an ideology, although globalisation is a huge challenge for every person on the planet, so you either have to be for it or against it. Although I am handicapped by my age, because modern technology is primarily intended for young people. Still, I have children and think it’s good that they were born later, and not in 1946, like me.”

I’m sorry that there are no more intellectuals who think “in the European way”, who are convinced that the EU is a better society. However, I think it will be educated young people who will create the conditions for a better life in this region. And change the way of thinking

From his marriage with his first wife, Oliver Olja Katanić – a successful former TV Belgrade journalist, Goran Milić has his eldest daughter, Lana Marija Milić, who works as a lawyer in Zagreb. After Olja’s death, he married Ana Lončar, who is known to the Croatian public, under the name Ana Milić, as the editor of the Good Morning Croatia programme on Croatian national television station HRT. From that marriage he has a son, Marko, who is named after Goran’s father and who, like his grandfather and father, graduated in law. He is today a close associate of Croatian Prime Minister Andrija Plenković:

“Marko was 17 years old when he first went to the Parliament. He knew that he would study international law, and everything he learned in the Parliament was important to his future studies. At one point he joined the HDZ [Croatian Democratic Union], began working with current Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, serving his assistant when he became a European parliamentarian. He was also with him when he won internal party elections against Karamarko, and he’s still with him today. I love the fact that Marko is so young but wants to continue learning, educating himself, improving himself. He won a scholarship to go to China, but is still considering what he will do. There are other invitations, for example to be some type of media advisor in the Croatian Interior Ministry, but he’s sufficiently experienced and independent to decide the best option for himself.”

When war broke out on the territory of the former Yugoslavia, Goran’s 800-square-metre family house in Slano was destroyed. Goran bought an apartment in Slano and continued spending time in the birthplace of his ancestors on his father’s side:

“After so many years, I’m again a Slanjanin and again enjoying it. Ana and I were there this year for Easter and I’m delighted that I again have a place where I can spend time by the sea. Admittedly, my life unfolds between Sarajevo – where I work part-time for Al Jazeera, have lectures, work on documentary films and do various other jobs – and Zagreb, where Ana and Marko live and where I spend most of my time. I have been well received in Bosnia for a long time and feel good there. I greatly appreciated Alija Izetbegović. Actually, I left old friends all over that former country, and acquired new ones, and today’s there’s almost no part of that country where I won’t go to shoot some documentary story.

I commence from the following fact: around 150,000 foreigners are living on the territory of the former Yugoslavia today – from diplomats, representatives of various organisations, institutes, associations etc. to corre-spondents of numerous media companies, soldiers and spies. I am someone who has passed every village, from Gorica to Đevđelija, in recent years; I know the place perfectly and am someone who will acquaint them with that place perfectly. I think that’s a good recommendation for me to also have something to do in the coming years.”

In seeking to shape himself as a journalist, Milić met the greats of Yugoslav and world journalism. He acknowledges the great Jurij Gustinčič, who was the New York correspondent of Belgrade daily Politika, or Dragiša Bošković, who also wrote from New York, but for Ljubljana-based daily Delo. He considers Aleksandar Tijanić as having been a great journalist, but one that only functioned mentally to the borders of the former Yugoslavia:

“Jurij, who we nicknamed Jurka, and Dragiša had global worldviews, and – unlike many other journalists of that time – weren’t dogmatic. They were the loyal system for which they worked, but they were very well aware of its shortcomings. Jurka was a communist until the end of his life, and he died at the age of 90. Today I think I was raised and educated on erroneous premises. I remember that, as Yugoslavs, we had problems with all the neighbours surrounding us, while today we know that a good foreign policy is based on the necessity of having the best possible relations with neighbours. We, as Yugoslavia, constantly accused our neighbours of being unfriendly towards us all the way until 1977.

And then it just so happened that I was meeting with Edvard Kardelj [celebrated Slovenian journalist and member of the Presidency of SFR Yugoslavia for Slovenia], who had invited all presidents of the presidential committees of the republics and provinces, and all presidents of the central committees, while there were only a few editors, including myself, as the editor of the foreign policy section of TV Belgrade. Kardelj, who was then appearing as the second man in the country, said that he was speaking on behalf of President Tito as he announced that the SFR Yugoslavia foreign policy had to change and that he would personally begin this change with Austria, though it was tough for the Slovenes to accept what Austria was doing to the Carinthian Slovenes.

He then spoke about new guidelines for behaving towards neighbours, which at that time was the toughest for the Macedonians due to their relations with Greece, but the country took a new path, which was very significant. That’s because you can’t have problems with your neighbours while your friends are Kenneth Kaunda [then Zambian presi-dent] and Julius Nyerere [then Tanzanian president]! Pretty unnatural. Someone yelled on the streets of Belgrade during the meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement ‘Long live Selassie, a communist from Asia,’ and he [Haile Selassie] was an emperor who wasn’t even from Asia, but rather Africa.”

Perhaps it would be most accugrate to say that I am today a man without an ideology, although globalisation is a huge challene for every person on the planet, so you either have to be for it or against it

Pondering the fact that 101 years have now passed since communism was instigated in Russia, Goran says that during that time there was a lot of wandering, lots of mistakes, many people who suffered, and that this system essentially brought no new values and no new products:

“Come on, tell me which product that was made in the socialist countries would be desirable for a consumer in, say, Austria, that they didn’t already have a much better and higher quality version of. I admit, only Elan skis – that were created, not by chance, in socialist Slovenia – were the best and have remained excellent to this day. Of course, we also had Vegeta for export, but only to the Eastern markets, as well as cables from Svetozarevo, but only exported to Algeria and rarely for the West. Some would say that all of that could have survived if privatisation hadn’t ruined everything, which is a view with which I really disagree.

Because everything that realistically could have survived actually did survive. You couldn’t maintain Energoinvest with 52,000 employees after such a war in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The market is cruel, of course, and the battle for the market has put everyone in their place. You used to pay a lot in Moscow for Yugoslav wine, while today you have to pay someone to place it on shop shelves alongside the best wines from around the world. You used to be able to live in Moscow with two pairs of Varteks jeans, but where would you go with them today?”

Goran dealt continuously with the differences between the countries of the former Yugoslavia for years, and today he is again working on a series of shows that will address these countries as they stand at present. He says that the differences between these countries are proportionally the same as they were in 1914, prior to those countries being united in Yugoslavia. They may even have increased slightly:

“Those differences have perhaps actually deepened somewhat between, say, Croatia and Serbia, because the average monthly income in Serbia is less than 400 euros, while in Croatia it is 800. That’s a lot, because it never previously occurred that there was a two-to-one ratio on income. And everything else is generally the same. The largest bank in the region is still Zagrebačka banka, as it was in 1914, and it is again not owned by local people, but by foreign-ers. These differences between the peoples are not great, but we are still lagging far behind Austria, for example.

When it comes to these differences, there is one example that is interesting, although it is not the only one: the president of the municipality of Bihać [Bosnia-Herzegovina], for example, until recently had a salary three times as high as Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and the same as Croatian President Kolinda Grabar Kitarović. And if we were to compare the former northern part of SFR Yugoslavia with its south, Slovenia has – on the whole – shifted a long way from Macedonia. But you have to view that in light of the fact that Slovenes are heavily indebted compared to Macedonians. While the least indebted is Kosovo, which has a debt of just a billion dollars, but that’s because nobody wants to invest there. The economy is too complicated to compare, but when it comes to quality of life there’s no doubt that Slovenia and Croatia have shifted away from the others and are already close to the average European standard.”

The economy is too complicated to compare, but when it comes to quality of life there’s no doubt that Slovenia and Croatia have shifted away from the others and are already close to the average European standard

As long as he is dealing with issues and condi-tions in the states that emerged from the former republics of the SFRY, Goran is extremely interested in the political situations of other countries:

“I was happy when I started touring the Balkans five/six years ago, and – with the exception of some tension – I got the impression that the borders are established and won’t be able to be changed. There are neither the weapons nor the will for that. However, over the past year I haven’t heard anymore utterings of the obligatory statement about the compulsory sentence anymore about the immutability of borders, so that worries me slightly. That has been declared impossible a hundred times in the history of the Balkans, and yet it has still happened.”

He’s sorry that there are no more intellectuals who think “in the European way”, who are convinced that the EU is a better society. However, he thinks it will be educated young people who will create the conditions for a better life in this region. And change the way of thinking.

| FRIENDS “I left old friends all over that former country, and acquired new ones, and today’s there’s almost no part of that country where I won’t go to shoot some documentary story.” | COMMUNISM “I think that communism was a respectable idea, but unimplementable, because it is … against human nature.” | MARKET The market is cruel…You used to pay a lot in Moscow for Yugoslav wine, while today you have to pay someone to place it on shop shelves alongside the best wines from around the world |

|---|