“We mustn’t remain silent. We have to constantly be at the epicentre of crisis events. Where churches are set on fire, the hodja hasn’t done do his job; where mosques are set on fire, the priest hasn’t done his job properly.”

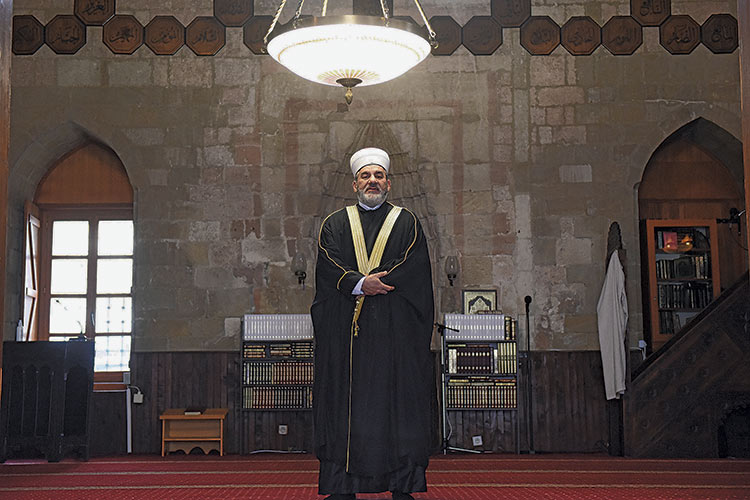

Whenever Mufti Mustafa Efendi Jusufspahić’s voice is heard in public, it acts as a soothing ointment. And that’s the case whether he’s discussing coexistence, society and the future, or critiquing certain phenomena and events. That’s because criticism that’s born of an authentic desire to make our world a better place has healing properties. Mustafa Efendi Jusufspahić is Mufti of the Belgrade Islamic Community of Serbia, but also a major and chief military imam of the Serbian Armed Forces and the executive director of Halal Agency Serbia. We spoke with him to discuss the situation today in both Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia, the role of religion in society, how we can all live together and how chains of hatred can be broken, the current position of the Islamic Community of Serbia, but also what we should consider when thinking about the pandemic.

How do you see the future of Bosnia- Herzegovina? What role does religion play in that country and what should its role be?

Bosnia-Herzegovina is a sovereign country that nurtures within it a tradition of all monotheistic religions and cultures dating back many centuries. Religion there, as in all countries, should be a factor that unites people with the aim of satisfying our common Creator. Unfortunately, there is a lot of politics in religion today, and very little religion in politics. The people of the former Yugoslavia were estranged from religion for a long time, and channelled towards a system that belittles God. Such a system led to an eruption of discontent, because people are inherently connected to their Creator.

Many political parties have sought to abuse the influence of the Church and religious communities, using the pulpits of altars and minbars to promote their political platforms. Some of them even succeeded, while individual religious figures have even discarded their religious robes and donned the suits of politicians, abusing their influence over the religious community for the sake of personal political interest. The state didn’t handle that well, so – in the spirit of ‘democracy’ – it permitted that kind of work on two parallel tracks, which in our case would most often lead to a result called ‘political Islam’. Religion should be, and should remain, a stabiliser of relations and an eternal norm of harmonised relations between spirit and body, for the sake of order, both of the individual and in interpersonal relations and society as a whole. It mustn’t be abused, while it must be based on universal values: justice, solidarity, goodness, freedom and equality. Justice should be the measure that forms the basis of the law and the legal system of social democracy.

A legal system built on foundations of justice enables the establishing of the rule of law, i.e., the rule of law as a guarantor for the maintaining of social democracy. With the help of justice, social democracy becomes antiauthoritarian and depersonalised, preventing the imposing of anyone’s arbitrariness. Solidarity, as a universal value, enables people living in a system of social democracy to have empathy for all those who are threatened, feel insecure and whose existence is in question.

Religion there, as in all countries, should be a factor that unites people with the aim of satisfying our common Creator. Unfortunately, there is a lot of politics in religion today, and very little religion in politics

What do you think about the raising of young people who belong to different ethnic and religious groups, and in some places even attend separate schools and listen to political messages that often target others in the community? Where is the hope?

From my perspective as the religious figure of a religion that promotes peace, I can’t imagine such segregation. Shaping young minds in order to create ‘children of war’ is the most inhumane way of life. We must fight that openly and discuss it as often as possible. The wars of the 1990s, and their outcome, stand as testimony to the fact that this approach didn’t bring any good to anyone. We were in our 20s during those years and couldn’t even know, while today – from my perspective as a 50-year-old – I loudly raise my voice against this type of upbringing. It is also a sin to remain silent about it.

You once wrote that the chain of hatred must be broken in order for our descendants not to be immersed in it and thus destroyed. How can that chain be broken? And I don’t mean only in our country, but generally in communities that have gone through conflict and continue to be plagued by it.

Yes, that’s actually connected directly to the last question. We mustn’t remain silent. We must be constantly at the epicentre of crisis events. Where churches are set on fire, the hodja hasn’t done do his job; where mosques are set on fire, the priest hasn’t done his job properly. You can be certain that this is so for the most part.

At the start of the 1990s, your father, together with other religious representatives from the former Yugoslavia, participated in an international peace conference in Switzerland. They were jointly addressed on that occasion by a speaker from one of the European delegations who began giving advice on peaceful coexistence, to which the mufti replied with something like: “Sorry, but I think there’s been a mistake. I had the impression that you called us here to give you a lecture on how to live together, as we’ve been living together for hundreds of years”. What would be the applicable guidelines to ensure peaceful coexistence?

You see, upon the outbreak of the war in the 1990s, my father went to Patriarch Pavle in his capacity as Mufti and showed him a quote from the Quran which read:

“… and among members of other faiths you will find that your best friends are Christians, because they have monks and priests who are not haughty. When you talk to them about the unity of God, you see a tear of piety in their eye…”

The patriarch was surprised by this verse from the Quran and asked if it had always been there. ‘Of course,’ my father replied, ‘the Quran is the unchanging word of God and will not change until Judgement Day’. Patriarch Pavle then raised his right hand, swearing: ‘on the word of God, our hand will never be raised against you’. My father also swore on the word of God that our hands would not be raised against them either, and Belgrade remained free of conflict in all that unrest, even though it was home to around 200,000 Muslims.

My late father Hamdija was very proud of the good relations between the religious communities. Those relations were built during communism, which was a very difficult time for religion. Religious communities stuck together much better back then.

With this pandemic, man has been warned that he was set against his peer and that he must protect him more than has been the case to date. We must also be careful to kill the disease and not the patient

How is the situation for the Islamic Community of Serbia in our country today?

I hope that we, as Muslims in Belgrade, will also receive permission to build a mosque and an Islamic centre that’s worthy of the most important Balkan metropolis that is Belgrade.

To date this has always been a political issue, but now I hope it will become a simple urban planning issue. In our 55 years of work here, we’ve surely shown that we wish only the best for this country, for our beautiful Serbia, and that we deserve the same treatment as all traditional religions in this country.

And your life and relations within the neighbourhood?

I’m a Belgrader, a Dorćol native who was raised to view neighbours as being closer than family. Our Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, taught a lot about relations with neighbours, so much that we thought our neighbour would be our legal successor after death. That’s a religious obligation of every Muslim in relations with their neighbourhood. Just take a stroll around Belgrade and ask a random passer-by about the Jusufspahić family. Without false modesty, I know that we’re loved by a large number of my fellow Belgraders.

We witnessed unpleasant scenes in Priboj and Novi Pazar recently, with the singing of songs that incite religious and national hatred. You responded by writing a mes sage on Twitter, concluding: “A Muslim isn’t one who curses and threatens others and, as far as I know, nor is a Christian either. People, God has bequeathed us to one another”. How do you view these incidents and how appropriate was the society’s reaction to them?

I consider deeply: your child is born. There’s nothing more beautiful than a healthy child.

You rejoice with your friends and enjoy the Godgiven, healthy fruit of your loins. You request a song about the crimes in Srebrenica and enjoy the pain and suffering of murdered people. What is wrong with such minds? That’s definitely a job for pathology. Where is that rock bottom?

Society dare not be silent and must react. I’m glad that President Vučić went to the scene to condemn that. That’s responsibly taking action. Condemning and punishing is the only way to prevent such incidents from reoccurring in the future.

We’ve been in a pandemic for nearly two years. What do you think we should have learned by now, and what should we change in our mutual relations?

God gives us tribulations in order to bring us closer to one another. Man is a social being and when you place him under quarantine, he only then realises the essence of his existence. With this pandemic, man has been warned that he was set against his peer and that he must protect him more than has been the case to date. We must also be careful to kill the disease and not the patient.

By Jelena Jorgačević