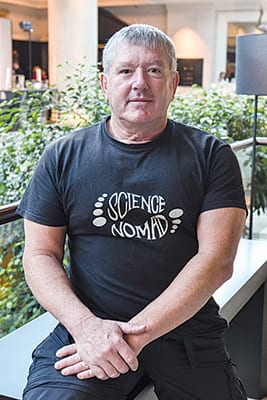

Dr Stuart Kohlhagen, PSM, is the Director of Science and Learning at Questacon. He has been a part of Questacon and the Science Circus since its very beginnings when he helped pioneer the development of exhibits, science demonstrations and shows. He is passionate about simple, open-ended, hands-on exhibits, enquiry-based activities that provide learning opportunities and spark curiosity.

He has been active in capacity development programmes for science centre staff and educators across the world, in South Africa, Lesotho, Indonesia, Korea, Brunei, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and elsewhere, as well as leading the development and delivery of a range of professional teacher development programmes in Australia and internationally.

Famous thinker and astrophysicist Carl Sagan once said: “We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology”. The quote is from 1990, but it has become increasingly relevant over time. How can we change this dependence in ignorance and make STEM more accessible?

STEM does not need advanced equipment… STEM and the support of 21st-century skills need teachers with the confidence and training to nurture curiosity while leaving space in curricula for students to have time to work on problems and challenges… challenges that they find relevant, but which are also deep.

Society, technology and the world around us are changing rapidly. How can we “future proof” education, and prepare educators for the future?

Again, it is a matter of supporting dispositions… Things like problem-solving, critical thinking, resilience and not worrying too much about specific technical skills. These will be outdated by the time students graduate. But being a problem solver and self-educator will last a lifetime.

You’re the founder of The Science Nomad – a project supporting local educators and teachers that have access to more modest tools and materials to get the most of them and spread knowledge. What are some of your favourite examples of creative solutions and ways to educate and share knowledge in this context?

Humble materials, powerful outcomes. The most critical aspect of my work comes from having a very clear focus on the outcomes I seek to achieve through my interactions with educators. As I say, activity is easy, while impact needs planning. So, I will work with communities to understand the barriers preventing change, or using hands-on learning and curiosity-driven education. And to identify small but real things that educators can do now to foster 21st-century skills. One project I did in Zimbabwe, in Bulawayo, was with pre-service educators being trained to work with children afflicted by various disabilities (deaf, blind, autistic). The simple activities you share are ideal for these learners, as they utilise and can involve a wide range of sensors. After the training, I received emails and messages from many of the teachers, who are now out in communities across Africa, using and sharing these approaches. This is deeply rewarding for everyone involved.

You have worked around the world with many different cultures and nations. What are some of the main differences (and similarities) you’ve come across when it comes to education, teaching styles, teacher-pupil interaction and the way we share knowledge?

There are more similarities than differences. The challenges shared by teachers are nearly universal – too much being packed into the curriculum, too many things other than teaching occupying their time. Attitudes to education differ in some communities, but in most developing countries it is understood that education is the pathway to development, with the differences in access to it, and the quality of teachers.

The challenging part of working as an individual, especially in the area of informal education/ and support of formal education is finding consistent funding, so programs can be developed and PLANNED far enough ahead to ensure great outcomes

You’ve worked as Director of Science and Learning at Questacon, the National Science and Technology Centre, for over 30 years. Partnerships are central to Questacon’s ability to engage with communities through different programmes. Can you tell us more about this model and what’s needed to engage all the various stakeholders – from the government and foreign countries, via corporations, to local volunteers – to make such projects work?

Both while I was a director of science and learning at Questacon and now, as a solo Science Nomad, the key is finding willing and active partners, which can – with some injection of support, examples and mutual linking – cannot only create an event, but can move to become a node and adopter of these approaches. There is no competition for audiences – we will never serve all who need help. However, by working with those agencies that have the scale and resources, but that may lack the examples of effective approaches, even an individual can have an impact at scale.

What are some of the most challenging parts of your work – and what are some of the most rewarding parts?

The challenging part of working as an individual, especially in the area of informal education and support of formal education, is finding consistent funding, so programmes can be developed and planned far enough in advance to ensure great outcomes. The work tends to be opportunistic and often requires self-funding to get things started. This makes it hard to have repeat interactions, and that is critical to getting a real capacity building or cultural change. This is sometimes supported by DFAT for a few years, as was the case with projects in Africa, India and Thailand, and the results are incredible when this happens. It is rewarding on the day to see the smiles, hear the laughter and feel the energy, but even more than this is the reward of hearing stories recounted long afterwards of how activities are being continued, further shared and spread.

Innovation is crucial for economic growth and social welfare. How can we develop the capacity for innovation of a community or country through education?

Two critical components for a country: to bring what “industry/society” needs and what the schools see as their priority/their performance indicators.

As long as schools (teachers and students) are accessed, regarded and graded based only on standard academic results (maths examinations, science tests and literacy benchmarks), the time in school will only focus on that. These approaches exist (that I and others share) that can do this whilst also achieving the development of 21st-century skills. It is not very difficult or expensive to include these approaches alongside the existing approach. But if these are not given a formal value – a grade, a badge, a credential – the system won’t value them, and they will not be implemented or followed in a serious way.

One of the challenges regarding the fields of STEM is certainly the under-representation of women. How do we change this, and how can we fuel the next generation of female innovators?

Continue to profile role models, remove competitions and challenges that are framed by others (which may or may not have appeal to young women) – we should gauge or filter, or narrow the opportunity of HOW and in WHICH domain people (women) choose to follow in a STEM or general innovation pathway.

If you go way back to where it all began – what were your first contacts with science; and how did you choose this path for yourself?

I grew up in a small rural town. I had time, tools, and parents that let me try things, make things, explore and ask questions… and they either answered them or encouraged me to find the answers for myself. Once I had these attitudes, the rest was inevitable.

What would be your advice to Serbian kids that are curious about STEM?

Find Your passion, ask your questions, and develop the skills to answer them yourself.