By Sonja Ćirić “It seems to me an opera boom is underway. All directors (of theatre and film) strive towards this genre. That’s because it offers the kinds of tremendous opportunities that other genres don’t.”

Yuri Alexandrov is known to our public for his directing feats: his direction of La Traviata and Pagliacci on the Great Stage of “Madlenianum Opera & Theatre” represent the highlights of the repertoire on the Belgrade scene, and he is now set to present himself to Belgrade again, this time as the artistic director of the St. Petersburg Opera.

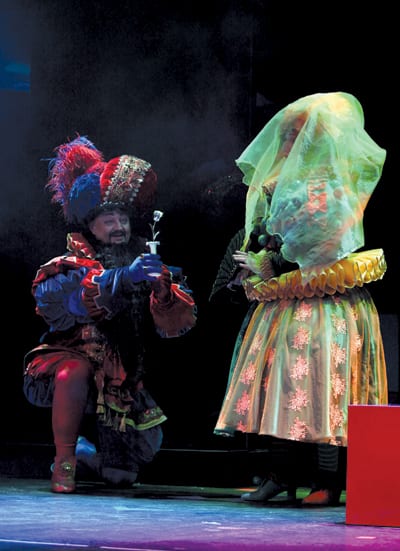

Namely, on 24th and 26th June, this opera’s ensemble will make guest performances at Madlenianum with Rodion Shchedrin’s opera Not Love Alone and Sergei Prokofiev’s Betrothal in a Monastery. This is considered the greatest guest performance in our capital since the beginning of this year.

It was thirty years ago when Yuri Aleksandrov, then director of the Mariinsky Theatre in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), proposed that the City authorities establish an opera that would satisfy the tastes and needs of a new audience, focused on global changes in art. Thus emerged the St. Petersburg Opera, which is today one of the most recognisable opera companies in Russia and around the world, with a repertoire that is primarily recognisable thanks to Alexandrov’s innovative directing solutions.

Aleksandrov has directed around 200 operas in Russia and around the world, and everywhere he has left the mark of his distinctive aesthetics, in which critics particularly emphasise innovation and experimentation. Thanks to such a reputation, Alexandrov was invited to direct Puccini’s Turandot opera on the stage of the Arena in Verona. Prior to him, no Russian had ever been invited there to direct an Italian opera. In the following interview, we attempted to at least touch on some of the myriad topics from Alexandrov’s career.

Why did you decide to present your theatre in Belgrade with a contemporary Russian opera and not a classic, given that the opera tradition is a trademark of your country?

– It should presumably be noted that the choice was made by the host party and that I was somewhat surprised by the choice, but also simultaneously encouraged because it testifies to the maturity of theatre culture in Serbia.

This means that people in this country are interested not only in the classical repertoire, which consists of several well-known operas but also in that which ensures Russian culture is celebrated.

Prokofiev and Shchedrin are two great Russian composers, but they are not so well known abroad and aren’t loved like, for instance, Tchaikovsky. That is precisely why we are so excited that the Serbian side made such a choice. As for the statement that the opera tradition is a trademark of my country – I doubt that because the Russian opera scene is developing in different directions.

We have avant-garde directors and traditionalists, but also people like me, who try to find a consensus between traditional operas, known to a wider circle of viewers, and avant-garde direction. I am certain that a contemporary director should be unpredictable, like the times in which we live.

Do you think that opera, by being stuck in time, has contributed to its own loss of the popularity it enjoyed at the time of Verdi and Mozart?

– I don’t agree with the claim that opera has “lost its popularity”. On the contrary, it seems to me, an opera boom is underway. All directors (of theatre and film) strive towards this genre. That’s because it offers the kinds of tremendous opportunities that other genres don’t. As for being “stuck in time” … I think that it is more about the creators who deal with opera that have got stuck… In his own time, Verdi wrote La Traviata, and the result was a terrible scandal because that opera became a contemporary interpretation of problems that then existed in society.

It could be said that the topics of the operas with which you are touring in Belgrade are ‘everyday’ and familiar to everyone. The recent festival in Amsterdam saw performances of operas in which the main characters are American President Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Does this mean that contemporary life has become part of the opera? What does that say about opera as a movement?

– I can’t say that Prokofiev’s opera Betrothal in a Monastery, written according to Sheridan’s drama, is something “every day”. It is a story that’s full of humour and historicism, with the action moving from a tavern to a monastery, then from a monastery to a nunnery and so on …

That hardly fits into the context of everyday life. And if we are talking about opera Not Love Alone, this is a very special piece – it is the Russian Carmen. That’s how we interpret it.

The everyday life that exists in this opera has stayed in the past and for us, it has now already become history. Kolkhoz farms and party discipline have remained in the past, and sometimes it is useful to go back and think about that … The main things in opera are – musical dramaturgy, strong passion and a tragic finale. Characters like Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, for us personally, have not yet cheered us with a story worthy of an opera stage.

While directing the classic operas La Traviata and Pagliacci, which I mention only as they are the two known to the Belgrade audience, you emphasised aspects in them that weren’t previously, thus in La Triviata’s Violeta we see primarily a lonely person and not a woman who sells her body. Would you please comment on this?

– Loneliness is a very complex problem in our society. Regardless of the population density, there are a lot of lonely people. And the mere fact that people sell their bodies is just one of many problems that are interesting to me as a director. There is a lot of selling in the modern world and it is difficult to surprise someone with that: someone sells their body, another sell their voice in the government, while a third sell state secret. But the theme of loneliness, which you very correctly mentioned, exists, is eternal and should be addressed.

Why did you want to form your own opera company? Would your life not be simpler if, for example, you were just a director in some theatre?

– Of course life would be easier, but on the other hand, it would be less interesting. Establishing your own theatre implies creating the kind of atmosphere in which you can implement your plans to the maximum. This is a creative laboratory that every director fantasises about. It is something completely different than this is all connected with worries and the human factor.

The human factor is a very important aspect, especially when you work with young artists because they need help – not only professionally, but also human, financial and social help. An artistic director must worry about all of that. But I have not for one moment regretted that I formed my own opera theatre.

You managed to form the St. Petersburg Chamber Opera with the assistance of the City administration. What is the State’s attitude like regarding the needs of artists for change and modernism in culture?

– I don’t know how to interpret “change and modernism”, because culture should not be modernised. The means of production can be modernised, while culture – that is what was given to us by God.

And in it, we should find that which is current for us today. When I direct a play, I only think a little bit about who will understand me and how.

For me, it’s important that I understand myself, what I’m thinking about today, what worries me the most and which topics I would like to discuss with my viewers. I’ve never strived to “modernise culture”; I just share my feelings with the audience, and if it’s interesting to them, my energy doubles. As for the city administration … Of course, without the help of the City, we wouldn’t have been able to get the building, we wouldn’t have been able to support the troupe … Of course, the City helps us a lot. We have been renovating our theatre for eighteen years and we hope that the restoration will one day end. If we are talking about some more global issues, we would like the state to devote more attention to culture, because the spiritual domain of life is very important for every society.

It is believed in Belgrade’s cultural circles that the same group of people comes to opera performances. What is your experience; who listens to performances on the repertoire of your opera company?

– In the thirty years of the existence of the Saint Petersburg Opera, a certain circle of people formed who know why they come to the theatre. These are people who know that we have a high-quality culture of music and performing arts. The people who come to us are interested in seeing new, young performers, who understand that opera today is a complex art in which the sense of what is happening bursts out in one of the first places.

Direction has become one of the most important means of expression. I am joyful when people come to see the direction of Alexandrov when they come to hear our young singers; I’m overjoyed when the audience is thrilled by our stunning interiors, which we struggled to restore. I think that the arrival of every viewer in our theatre is primarily the sum of impressions. We work actively with the public and try to enlighten and attract youngsters.

How do you form the repertoire of your own opera company? Do you pay attention to the tastes of the audience?

– Not being bothered about the taste of the audience means condemning yourself to an empty auditorium. However, when I founded my own theatre, I imagined it not only as a place where I would satisfy my creative ambitions but also as a school for soloists. Contemporary singers, even those with good voices, often don’t master their profession to the extent that is demanded by the modern theatre. As for the repertoire, we are very interested in classics and, certainly, contemporary music, without which no lively theatre can exist, and that’s why our repertoire includes Shchedrin, Prokofiev and Shostakovich.

How do your colleagues from other Russian opera companies view your innovative direction? Do they perceive that as the right way to ensure the durability of opera as a musical and theatrical form?

– To be honest, I am not particularly concerned about the opinions of my colleagues.

I always endeavour to very carefully express my opinion, because I understand perfectly how difficult it is to direct an opera performance. That is a huge job.

I always endeavour to very carefully express my opinion, because I understand perfectly how difficult it is to direct an opera performance. That is a huge job.

I’m interested in various aspects of the genre. Today I can direct a show in the avant-garde style, then tomorrow present a classical show. I sometimes do fairy tales for children, and sometimes for adults. But, whatever the case, on the basis of my shows is the highest performing culture of the artists with whom I work. Likewise, I am also obliged to express the main thought of the composer, and that is sometimes very well disguised.

You are known for your specific work with singers, for your ability to lead them to do things they didn’t even know they could do themselves. How is that done? How do you turn an opera singer, who has learned that the only important thing on stage is to sing an aria properly, into a person of flesh and blood, a person who has a life story with which the audience can easily identify?

– Every soloist can reproduce the voices written by the composer, but in order to properly perform even a single aria and not a whole show, it is necessary to have a soloist who is able to become a living person on the stage. If that does not exist, nothing worthwhile can be achieved.

Today the notion that presents musical dramaturgy, expressed in action (in plastic), is one of the main notions governing opera. Birds also release their voices and sing very nicely, but there is no meaning in that.

The main task of the soloists of the Saint Petersburg Opera is to master the system of intonation. If the show that soloists perform includes human intonations that immediately captivates the audience. If the opposite occurs, no union of sense and sound is reached.

Have you perhaps had a chance to check out any Belgrade opera production?

– Unfortunately not, but I hope that I will, when such a possibility arises, certainly do that.

The goal of guest performances is to exchange experiences and knowledge. After each such encounter, emotion remains that enriches people. If that is indeed the case, and it is, why don’t we visit each other more often? Who or what does that depend on?

– I think it depends on the Lord God, and we are left to pray and hope for new meetings.