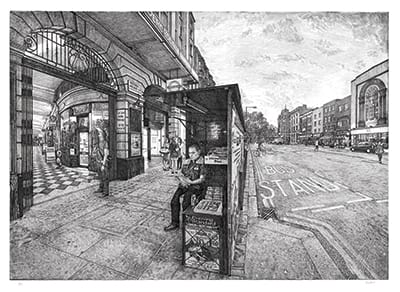

This is the first solo exhibition to bring a substantial body of Head’s recent work together – twenty-four paintings, drawings and etchings were displayed in the exhibition.

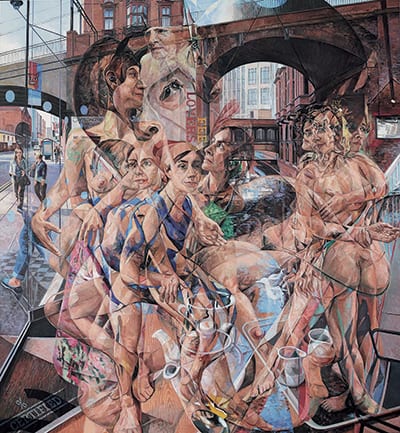

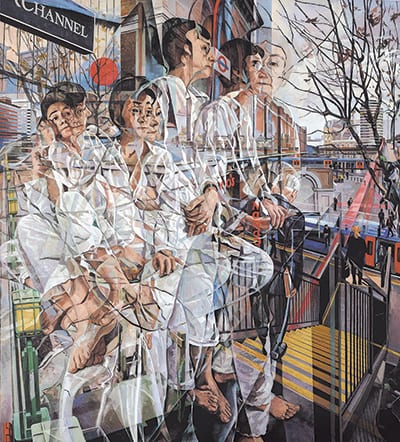

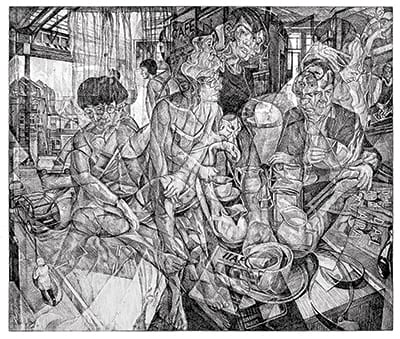

Born in England, in Maidstone, Kent, Head has garnered much acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic over the many decades of his career. This exhibition, aptly titled, bears witness to the way Head capture life around him. His highly complex compositions of human activities are zoetic and energized. And, unlike past Photorealists, Head does not reveal a single moment frozen in time. Instead, with deft ability, he captures multiple perspectives with multiple concurrent timelines, moving through time and space.

These fragmented urban depictions, most often with figures are in essence time-lapsed compilations. The compositions are highly engaging and immediately fascinate the observer. Time seems to come to a kaleidoscopic halt on his canvases and his subjects are masterfully rendered.

Seen against Head’s forerunners such as David Hockney and Lucian Freud, and of his contemporaries such as Peter Doig, it was clear that Head had established a unique position in the contemporary arena. In one of the show’s highlights, Les Souvenirs du Café Anglais the artist characteristically fractures a scene from his familiar environment.

The painting, which was previously shown in, REALITY: Modern and Contemporary British Painting, is simultaneously a study in motion and stillness, tantalizing the viewer. Similarly, Summer Ark, Wash Day with Actaeon and Siddal’s Ferry are based on observations from the rural Yorkshire village in the North of England.

Seen against Head’s forerunners such as David Hockney and Lucian Freud, and of his contemporaries such as Peter Doig, it was clear that Head had established a unique position in the contemporary arena

A child prodigy beginning his instruction at the Reeds Art Club at the age of eleven, Head later attended Aberystwyth University. In 1994, he became Chair of the Fine Art Department at the University of York, lecturing on method, theory and art history. He also began participating in exhibitions throughout the UK, Europe and America. He was commissioned in 2005 to create a painting of Buckingham Palace to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth.

In 2010, Head was invited by the National Gallery in London to show three large-scale paintings of the city; the exhibition drawing record attendance and receiving myriad accolades.

One of the primary differences between Head’s painted realities and the reality of everyday life lies in the way space is defined. Head does not present a vista or view as a camera, he shows an entire environment over time, and if we were to try to replicate seeing one of his environments in real life we could not do it by visiting the location. As a consequence Head’s paintings are more like the record of a living human body wandering around a location, rather than a static snapshot of a part of it. Consequently, his work most closely resembles a movie camera panning around a scene, but the closest painting equivalent is in the multiple viewpoints, shifts of scale and games played with time seen in a Cubist painting by Picasso or Braque.

In earlier works, Head used a realist language of painting to render his experience into something coherent and whole. However, in later paintings, the disjuncture of time and space remained visible in the paintings.

In interviews, Head has always insisted that the language of realism he uses is not the same as the language of photography, and it is true that his paintings do not resemble photographs. Indeed, Head has been consistently critical of the futility of painters copying photographs. In this Head’s previous work as a neo-classical painter is significant as his spatial constructions are derived from classical ideas of perspective rather than being imported from a camera, computer or other machines.

In this, it appears significant that Head has stated that his use of perspective is not bound by pre-determined rules in a mechanical way, but evolves during the process of making each individual painting a process a camera cannot match. This means there is no predetermined vanishing point, where all the lines of perspective meet, but what Head calls ‘vanishing zones’. Head has also stated he ‘rejects the Modernist fragmentation and instead seek a seamless surface.’

Most recently Head has written of himself as a kind of anarchist artist, although he qualifies this by defining himself as a ‘private anarchist’ rather than a ‘political anarchist’

In terms of subject matter, Head tends towards urban scenes, particularly London, although he has also painted New York, Moscow, Los Angeles, Prague, Rome and Paris, amongst other places.

Most recently Head has written of himself as a kind of anarchist artist, although he qualifies this by defining himself as a ‘private anarchist’ rather than a ‘political anarchist’. This seems to relate to the increasingly definite anarchist artistic position Michael Paraskos has pursued in recent years and in particular Paraskos’s notion of anarchist art being an attempt to visualise an alternative reality outside society and culture. Paraskos has in effect defined culture in political terms as a manifestation of the predetermined state that imposes its will on the individual. In Head, this translates into opposition to predetermined visual imagery.

The most straightforward example of predetermined imagery is photography, but for Head, it is not the use of photography itself that is the problem, it is the adoption of the predetermined, or imposed, the language of the photograph by the painter. Notably Head also opposes other, nonphotographic, solutions to pictorial problems where those solutions are also predetermined, such as systemic art and contemporary Salon Painting.

Consequently, an analogy is made between the political anarchists’ desire for a society in which predetermined structures such as those offered by the state are abolished, and the artistic anarchists’ desire for an art world in which predetermined, or cliched, solutions to visual problems are also abolished.

This exhibition was organised in collaboration with Landau Fine Art.