Pollock’s lifelong intensity and, at its peak, sublimity do not pale. The trajectory of his too brief career retains a drama, as evergreen as a folktale, of volcanic ambition and personal torment attaining a liftoff, with the drip technique, that knitted a man’s chaotic personality and, with breathtaking efficiency, revolutionized not only painting but the general course of art ever after.

It can be argued, and has been, that the matter-of-factness of Pollock’s flung paint germinated minimalism. There’s even, for anyone susceptible to it, a lingering nationalist sweetness: Pollock’s peak period as the V-E Day of American art.

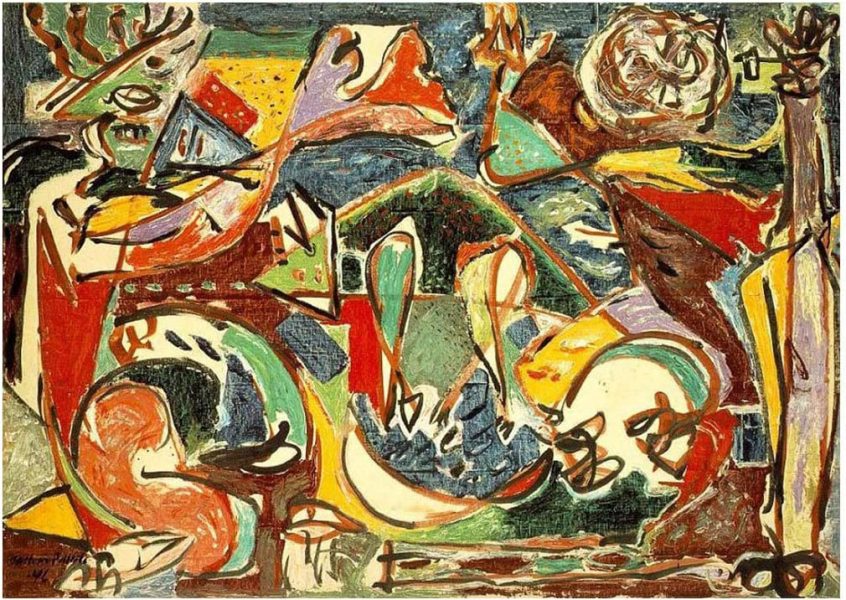

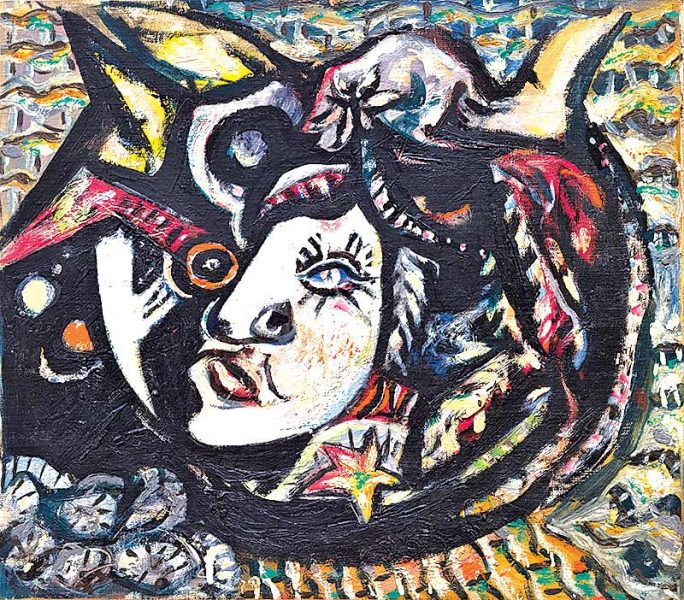

Paul Jackson Pollock was a major force in the abstract expressionist movement. His abstract mannerisms contained in his action paintings demonstrated Pollock’s great interest in exposing the workings of the subconscious mind through a seemingly incongruous arrangement of the subject matter. This dream-like art, based on familial memories of his environment, became Pollock’s responsibility to initiate his own personal and spiritual transformation and to influence others with this change towards a new pictographic imagery. Pollock underwent many changes in his portrayal of artistic imagery demonstrating that life can be layered in many ways but never hidden from oneself.

Pollock was eighteen when he arrived in New York from California, in 1930, and began to imbibe the influences of Thomas Hart Benton, who was his teacher at the Art Students League, and the Mexican muralists. The early works in the show are a thrill ride of quick studies, as Pollock devours those models and then suggestions from Picasso, Miró, and André Masson—paying off in lyrically inventive engravings, from the early forties, that are a revelation here. Pollock was always Pollock, though he was long in agonizing doubt, notably about his ability to draw. Dripping brought a rush of relief, as he found a steadying and dispassionate, heavensent collaborator: gravity. Drawing in the air above the canvas freed him from, among other things, himself. “Number 31” is the feat of a fantastic talent no longer striving for expression but set to work and monitored. He watched what it did. We join him in watching. Pollock redefined painting to make it accept the gifts that he had been desperate to give. Any time is the right one to be reminded of that.

In October 1945, Pollock married his long term lover Lee Krasner and in November they moved to what is now known as the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio in Springs on Long Island, New York.

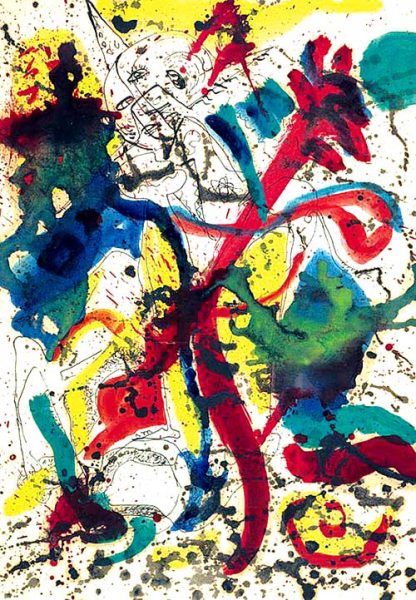

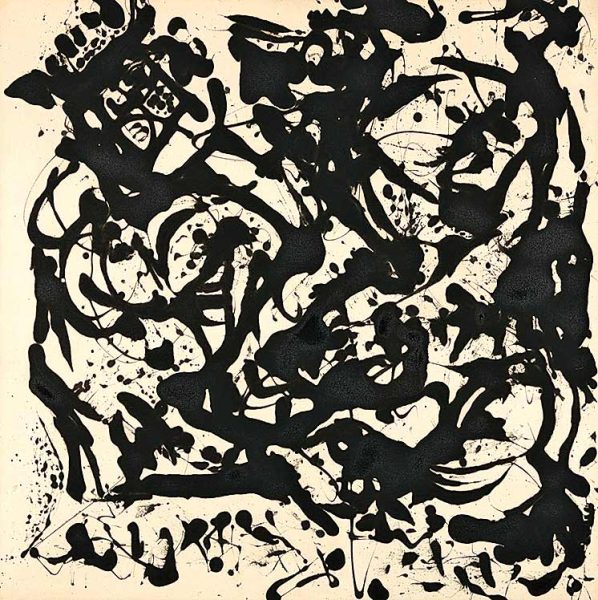

Peggy Guggenheim loaned them the down payment for the wood-frame house with a nearby barn that Pollock made into a studio. It was there that he perfected the technique of working spontaneously with liquid paint. Pollock was introduced to the use of liquid paint in 1936, at an experimental workshop operated in New York City by the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. He later used paint pouring as one of several techniques in canvases of the early 1940s, such as “Male and Female” and “Composition with Pouring I.” After his move to Springs, he began painting with his canvases laid out on the studio floor, and developed what was later called his “drip” technique, although “pouring” is a more accurate description of his method. He used hardened brushes, sticks and even basting syringes as paint applicators. Pollock’s technique of pouring and dripping paint is thought to be one of the origins of the term action painting.

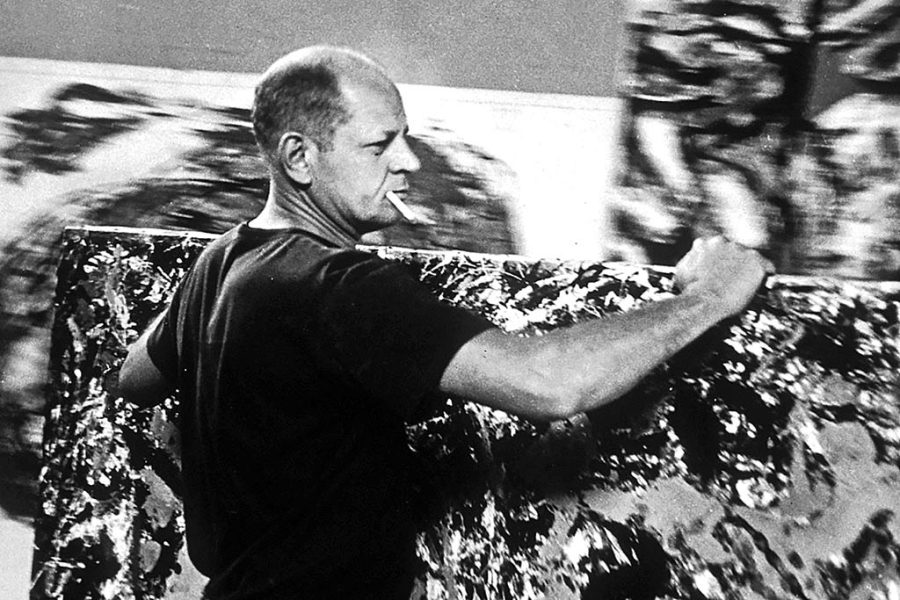

In the process of making paintings in this way he moved away from figurative representation, and challenged the Western tradition of using easel and brush, as well as moving away from use only of the hand and wrist; as he used his whole body to paint. In 1956 TIME magazine dubbed Pollock “Jack the Dripper” as a result of his unique painting style.

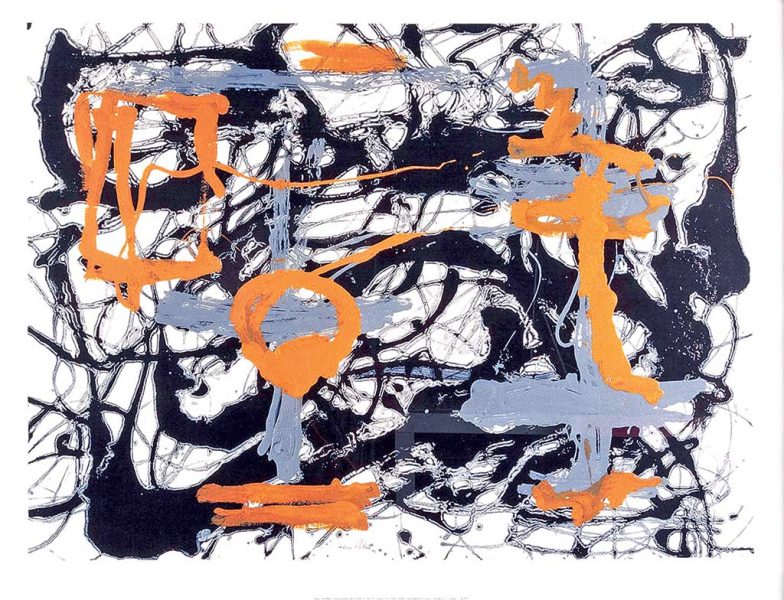

In the late 1940s, Pollock’s drip paintings categorically redefined how we understand art. This moment saw the art world’s center of gravity shift for the first time away from the museums and galleries of Paris and into the streets of New York. With his revolutionary new technique, Pollock effectively upended the existing framework of traditional painting practices. True drip paintings were—and still are—the ultimate in mid-century American avant-garde, and are rare to come across in the secondary market. Number 31 is a superb example. It is a fantastic, frenetic combination of rich hues—straight from the paint can. It stands as a brilliant demonstration of Pollock’s rigor and effusiveness.

Pollock observed Indian sandpainting demonstrations in the 1940s. Other influences on his pouring technique include the Mexican muralists and also Surrealist automatism. Pollock denied “the accident”; he usually had an idea of how he wanted a particular piece to appear. It was about the movement of his body, over which he had control, mixed with the viscous flow of paint, the force of gravity, and the way paint was absorbed into the canvas. The mix of the uncontrollable and the controllable. Flinging, dripping, pouring, spattering, he would energetically move around the canvas, almost as if in a dance, and would not stop until he saw what he wanted to see.

Studies by Taylor, Micolich and Jonas have explored the nature of Pollock’s technique and have determined that some of these works display the properties of mathematical fractals; and that the works become more fractal-like chronologically through Pollock’s career. They even go on to speculate that on some level, Pollock may have been aware of the nature of chaotic motion, and was attempting to form what he perceived as a perfect representation of mathematical chaos – more than ten years before Chaos Theory itself was discovered.

In 1950 Hans Namuth, a young photographer, wanted to photograph and film Pollock at work. Pollock promised to start a new painting especially for the photographic session, but when Namuth arrived, Pollock apologized and told him the painting was finished. Namuth’s comment upon entering the studio:

“A dripping wet canvas covered the entire floor…. There was complete silence…. Pollock looked at the painting. Then, unexpectedly, he picked up can and paint brush and started to move around the canvas. It was as if he suddenly realized the painting was not finished. His movements, slow at first, gradually became faster and more dance like as he flung black, white, and rust colored paint onto the canvas. He completely forgot that Lee and I were there; he did not seem to hear the click of the camera shutter… My photography session lasted as long as he kept painting, perhaps half an hour. In all that time, Pollock did not stop. How could one keep up this level of activity? Finally, he said ‘This is it.”

Pollock’s most famous paintings were during the “drip period” between 1947 and 1950. He rocketed to popular status following an August 8, 1949 four-page spread in Life Magazine that asked, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” At the peak of his fame, Pollock abruptly abandoned the drip style.

Pollock’s work after 1951 was darker in color, often only black, and began to reintroduce figurative elements. Pollock had moved to a more commercial gallery and there was great demand from collectors for new paintings. In response to this pressure his alcoholism deepened, and he distanced himself from his wife and sought companionship in other women. After struggling with alcoholism his whole life, Pollock’s career was cut short when he died at the age of 44 in single car crash in Springs, New York on August 11, 1956. After his death, his wife Lee Krasner managed his estate and ensured that his reputation remained strong in spite of changing art-world trends.