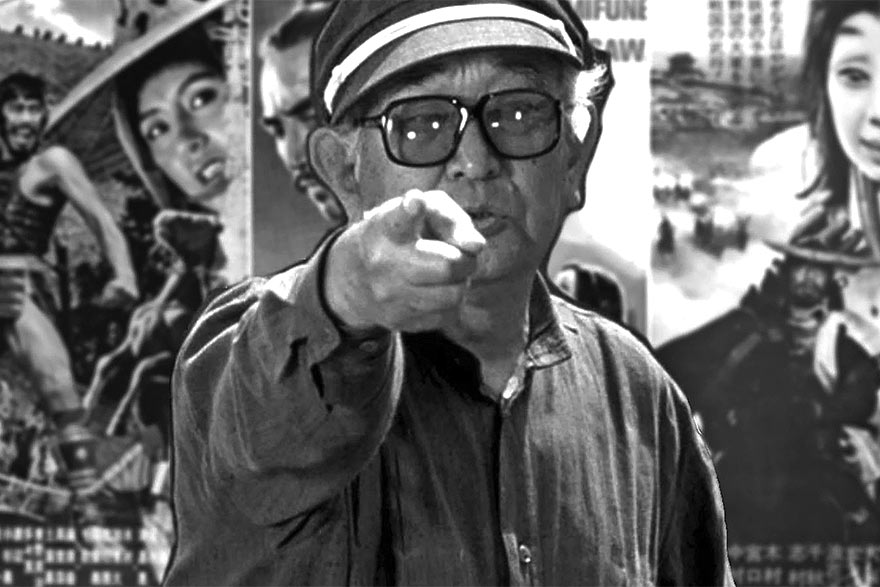

Kurosawa, the son of a military institute’s athletic instructor, became one of the colossal figures in film history — an autocratic perfectionist with a painter’s eye for composition, a dancer’s sense of movement and a humanist’s quiet sensibility. Dozens of directors have acknowledged his enduring influence

When Kurosawa’s “Rashomon” reached Western audiences in 1951, little was known outside Japan about the country’s cinema. That changed overnight with “Rashomon,” a compelling study of ambiguity and deception that provides four contradictory accounts of a medieval rape and murder recalled by a bandit, a noblewoman, the ghost of her slain husband and a woodcutter. The characters, Mr. Kurosawa said, have a “sinful need for flattering falsehood” and “cannot survive without lies to make them feel they are better people than they really are.”

Kurosawa’s calculated blend of Japanese folklore with Western actingstyles and storytelling techniques provided a link between the two worlds, reintroducing Japanese culture to a postwar global audience and leading to an amazingly fertile decade that saw him produce several films that have widely been acclaimed as among the finest ever made, including “Seven Samurai,” “Ikiru” and “Yojimbo.”

“I suppose all of my films have a common theme,” Kurosawa once told the film scholar Donald Richie. “If I think about it, though, the only theme I can think of is really a question: Why can’t people be happier together?”

Tall and large-boned, Kurosawa mixed a workingman’s thick, powerful hands with the face of a professor, sometimes a very stern professor. He was known by colleagues, not always affectionately, as “the Emperor.”

Kurosawa’s ecumenical interests in Western literature, Japanese folk tales and American westerns led him to source material as diverse as Gorky’s “Lower Depths,” Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” and Ed McBain’s “King’s Ransom.”

He was a master of both of the most popular Japanese film genres of his era, the jidai-geki (a costume-action film involving medieval samurai) and the gendai-geki (a more realistic, often domestic drama rooted in contemporary Japanese life).

In her introduction to “Voices from the Japanese Cinema” (1975), Joan Mellen wrote: “It is possible to draw a line from Kurosawa’s finest film, “Seven Samurai,” which Donald Richie has called the greatest Japanese film ever made, back to Daisuke Ito’s “Man-Slashing, Horse-Piercing Sword” in 1930. But if Ito created the genre of jidai-geki, Kurosawa perfected the form and gave it so deep a historical resonance that each of his jidai-geki has contained within it the entire progress of Japan from feudal to modern times.’’

Kurosawa chafed when Japanese critics described his work as too Western. “I collect old Japanese lacquerware as well as antique French and Dutch glassware,” he said. “In short, the Western and the Japanese live side by side in my mind naturally, without the least bit of conflict.”

Stories of his perfectionism are plentiful. He once halted production to reconstruct a hugely expensive medieval set because he noticed a nail head was barely visible in one shot. For the climax of “Throne of Blood,” his 1957 samurai version of “Macbeth,” he insisted that his star, Toshiro Mifune, wear a protective vest and perform the scene while being shot with real arrows.

On the set, where he rarely brooked dissent, Kurosawa developed his own technique for filmmaking that allowed him to edit each day’s scenes that night and be finished with a rough draft of the film within hours of shooting the final scene.

He rehearsed all of the scenes meticulously, sometimes for weeks, then shoot them from beginning to end, using three cameras positioned at strategic points. “I put the A camera in the most orthodox positions, use the B camera for quick, decisive shots and the C camera as a kind of guerrilla unit,” he said.

This is quite different from the way films are normally made, beginning with a “master shot” that is then augmented with close-ups and reverse-angle shots that are pieced together into a final version. Kurosawa wanted his scenes to be a record of a single performance.

“The editing stage is really, for me, a breeze,” he said. “Every day, I edit the rushes together, so that by the time I am finished shooting, what is called the initial assembly is already completed. It’s not all that bad. I just stay for maybe an hour or an hour and a half after everyone has left. That’s all it takes me.”

While he was quite strict with his technical crew, Kurosawa was more patient with actors.

“It is really strange,” said Shiro Miroya, one of Kurosawa’s assistant directors. “Kurosawa, who can be a real demon at times, when he’ll scream out, “The rain isn’t falling like I want it to,” or “That damn wind isn’t blowing the dust right,” is always so terribly gentle with actors.”

Kurosawa described his approach this way: “Unless you can see, as an actor, what the director is trying to express simply by how he looks and acts himself, you are going to miss the finer points. When my cast and I are on location, we always eat together, sleep in the same rooms, are constantly talking together. As you might say, here is where I direct.”

Though internationally renowned, Kurosawa was not much of a globe-trotter. He spent most of his time, when not working at his Tokyo studio, at the nearby home that he shared with his wife, Yoko Yaguchi, a former actress, who died in 1984. They had one son, Hisao, and one daughter, Kuzuko, both of whom survive him.

Financial reversals following the release of “Dodeskaden” in 1970 combined with a persistent and painful ailment (later diagnosed as gallstones) led him to attempt suicide in 1971. Though he recovered, he seemed changed. After having made 19 films between 1946 and 1965, he made only 6 in the 28 years following “Dodeskaden,” although two of them are considered among his finest works: the historical epics “Kagemusha” IKIRU (1980), centered on a thief in feudal Japan who assumes a dead man’s identity and becomes heroic, and “Ran” (1985).

His final films, “Rhapsody in August” (1990) and “Madadayo” (1993), were poorly received and struck many as containing a new, strident note of Japanese nationalism. But his influence on American filmmakers continued unabated.

In 1960, Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai” was remade by the director John Sturges as “The Magnificent Seven.” In 1964, “Rashomon” was remade by Martin Ritt as “The Outrage.” In 1964, “Yojimbo” was remade by Sergio Leone as “A Fistful of Dollars,” then remade again in 1996 by Walter Hill as “Last Man Standing.”

And George Lucas has acknowledged “The Hidden Fortress,” a 1958 adventure by Mr. Kurosawa in which a princess is escorted to freedom with the help of two bickering peasants, as one of the inspirations for his “Star Wars” series, in which he replaced the peasants with two bickering robots.

Akira Kurosawa was born in Tokyo on 23rd March, 1910. His father was a former military officer who had become an athletic instructor at the Imperial Army’s Toyama Academy. His mother had come from a well-to-do merchant family. “My mother was a very gentle woman,” Kurosawa said, “But my father was quite severe.”

The Kurosawa family had once been in the feudal nobility, tracing its lineage to a legendary 11th century samurai, Abe Sadato. But they had been living in Tokyo for four generations by the time Akira was born and no longer had wealth or status.

Akira was the youngest of four sisters and four brothers. In the book he wrote about the first decades of his life, “Something Like an Autobiography,” he remembered himself as “a crybaby and a real little operator.” He also suffered from periodic seizures caused by a form of epilepsy.

While Kurosawa was in his second year of primary school, the family moved to the neighborhood of Edogawa and he entered the Kuroda School, where a charismatic teacher inspired an interest in painting. Kurosawa’s father encouraged this, but the family often did not have enough money to buy art supplies. Later, Akira moved on to a more militaristic middle school and gravitated toward a brother, Heigo, who shared his interest in art. Heigo, who was four years older than Akira, did not get along with their father and no longer lived at home.

Without his father’s knowledge, Akira spent much of his time with Heigo during his teen-age years. Heigo was very interested in a traditional form of storytelling known as kodan, which featured tales of samurai and often involved intricate, stylized swordplay.

But what Akira remembered most about those years was going to the movies with his brother, who had taken a job as a benshi, or silent-film narrator. “We would go to the movies, particularly silent movies, and then discuss them all day,” Kurosawa later wrote. “I began to love to read books, especially Dostoyevsky, and I can remember when we went to see Abel Gance’s ‘La Roue’ and it was the first film that really influenced me and made me think of wanting to become a filmmaker.”

When sound came to films, Heigo lost his livelihood. Shortly thereafter, with what at the time seemed to Akira to be no warning, Heigo went on a trip to the mountains outside Tokyo and killed himself.

“I clearly remember the day before he committed suicide,” Kurosawa wrote. “He had taken me to a movie in the Yamate district and afterward said that that was all for today, that I should go home. We parted at Shin Okubo station. He started up the stairs and I had started to walk off, then he stopped and called me back. He looked at me, looked into my eyes, and then we parted. I know now what he must have been feeling.”

Akira enrolled in the Doshusha School of Western Painting in 1927 and tried to supplement the family’s income with his work, but was never able to make much money. Finally, he postponed his hopes of becoming a serious artist and took piecework for magazines and cookbook publishers.

In 1936, desperate for cash, he noticed a small advertisement for Tokyo’s P.C.L. Studios, which later became the Toho Film Production Company. It was looking for a half-dozen young men interested in becoming apprentice assistant directors.

All applicants – there were 500 of them – were asked to present themselves for an interview and to bring along an essay they had written on “The Basic Defects of the Japanese Film Industry.” Armed with his own essay, a 26-year-old Kurosawa found himself facing Kajiro Yamamoto, then the most prominent film director in Japan.

Yamamoto later remembered the young Kurosawa as extremely intelligent and refreshingly honest. He recommended that Kurosawa be hired and, shortly afterward, took the young man under his wing.

Kurosawa worked as Yamamoto’s assistant for seven years. Finally, in 1943, he was given the chance to direct his first film, “Sanshiro Sugata,” a slick judo adventure aimed at the popular market. It was a box-office smash in wartime Tokyo. Kurosawa followed it with “The Most Beautiful,” a blending of documentary and dramatic scenes about Japanese women working in factories, and “Sanshiro Sugata, Part II,” another huge hit. He also made “The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail” at that time, but it was not released until 1952.

“During the war, I hungered for the beautiful,” Kurosawa said. “I therefore drowned myself in the world of Japanese traditional beauty. I perhaps wanted to flee from reality, but through these experiences I learned and absorbed more than I could ever express.”

After the war, Kurosawa found traditional, stylized storytelling too confining and hungered for realism and the kind of filmmaking he saw in the works of Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica.

In 1946, Kurosawa directed “No Regrets for Our Youth, “about persecutions in postwar Tokyo by elements in the Japanese right wing. “It was the first film in which I had something to say and in which my feelings were used,” Kurosawa said.

Two years later, he made “Drunken Angel,” a crusading drama about an alcoholic doctor in the Tokyo slums. The film made his critical reputation in Japan.

In 1950, Kurosawa released “Rashomon” in Tokyo. The Japanese critics thought it a commendable though not exemplary work, nowhere near the director’s best. Nevertheless, the film won the Venice Film Festival’s grand prize and an Academy Award as best foreign-language movie. Its success made Kurosawa Japan’s most famous and popular filmmaker.

“For the Japanese people, who had lost the war as well as their pride, this meant immeasurable encouragement and hope,” Kurosawa said.

His next film, a strange adaptation of “The Idiot” by Dostoyevsky, was poorly received. But he followed it, in 1952, with “Ikiru,” which some consider his finest work. “Ikiru,” which means “to live,” is entirely unlike the later samurai epics that would cement his international reputation. Set in contemporary Tokyo, it follows a joyless, dying bureaucrat, memorably played by Takashi Shimura, who decides to help slum parents build a playground. The film was immediately recognized as a great work, both in Japan and abroad. But it was soon overshadowed. In 1953, the Allied occupation forces rescinded the restrictions on the making of films and the freedom stirred an amazing burst of creativity. In that one year alone, Yasujiro Ozu made “The Tokyo Story.” Kenji Mizoguchi made “Ugetsu,”Kon Ichikawa made “Mr. Pu,” and Akira Kurosawa made “Seven Samurai.” It was the high-water mark of Japanese filmmaking.

Kurosawa’s four-hour epic, often referred to as among the greatest action films ever made, tells the story of down-on-their-luck samurai who agree to defend a small village from bandits.

Though he had a major international success in 1974 with “Dersu Uzala,” a Soviet production about the friendship between a Russian explorer and a Manchurian hunter, he remained elusive and incommunicative. It won the 1975 Academy Award for best foreign-language film.

Even in 1980, at the premiere of “Kagemusha” at the New York Film Festival, Kurosawa struck many as cold and distant, even hostile. To some, he seemed to shrug off the film, saying he would rather have made “Ran,” an epic version of “King Lear.” But the success of “Kagemusha” made “Ran” possible. When he returned to the New York Film Festival in 1985 with “Ran,” he seemed a changed man: friendlier, more relaxed, even granting a handful of interviews. “As my son frequently says to me now,” Kurosawa said in one of those interviews,” “Dad, you have changed completely. You are a much more relaxed, open person than you were.” I am not sure why this is. It is simply a greater degree of relaxation and peace with myself, not having the tension that I had before.”

Though he often diverted the conversation when asked about his approach to filmmaking, Kurosawa frequently described his attitude toward art in similar terms. “To be an artist,” he once said, “means never to avert one’s eyes.”

Kurosawa also once described a trip he made with his brother, Heigo, through the ruins of Tokyo after a massive earthquake in 1923. More than 140,000 people died in the fires that followed the quake. But as the pair moved through the ruins, Mr. Kurosawa said, his brother insisted that the young Akira look closely at the charred corpses.

“If you shut your eyes to a frightening sight, you end up being frightened,” Akira remembered Heigo telling him. “If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of.”