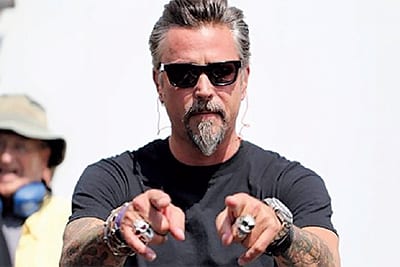

In the six years since ‘Fast N’ Loud’ first aired, Richard Rawlings has turned Gas Monkey into a multi-million-dollar brand

When Richard was growing up in Fort Worth, Texas, Raymond Rawlings always had a car or a motorcycle lying around.

“It wasn’t the nicest or the best, but it was his,” the younger Rawlings says. Ray wasn’t much of a mechanic, more of a detailer and tinkerer. On weekends, the guys in the neighbourhood would come over, mess around with whatever car Ray had at the time, and drink beer in the garage.

One of those guys who came around also taught Rawlings a lesson in negotiating that he still carries with him: “I was around 13. He said, ‘Son, you could buy a $10,000 car all day long for five grand if you have it in your pocket. Always carry cash.’ ”

All this made an impression on Rawlings. He started buying and selling and trading cars before he could legally drive them, getting advice from an old-timer in the neighbourhood on the technical side. (Like his father, he’s never been much of a mechanic.)

After completing high school, Rawlings worked as a suburban police officer, a firefighter and a Miller Lite delivery truck driver, but the entrepreneurial bug stayed with him. He started a company called Promo Wipes, which printed ads and logos on deluxe paper towels for car washes when he was just out of high school. That didn’t last, and Rawlings stumbled into a job selling printing and advertising.

He’d never sold anything but cars, but he gave it a shot and found he was good at it. He knew how to talk to people, and that was most of the job. But he also innately understood branding.

“Building brands and helping people figure out their identity — as far as a business identity and everything — was kind of my niche,” he says.

He tried to buy the company, but the owner wouldn’t sell, so he went out on his own with the help of a $100,000 small-business loan and opened a shop, Lincoln Press, in Dallas in 1999. By 2004, the company had done well enough for Rawlings to be able to offer a new Lamborghini Gallardo as an incentive to the first client to spend $1 million.

Asking Richard Rawlings how many cars he owns is a question with an answer that varies depending on the hour. At the moment, he says, there are 40, maybe 50, at his compound

Rawlings had always felt that there was something out there he was meant to do, something bigger. Lincoln Press wasn’t it. So he got out. The success and eventual sale of the company gave him “a little bit of pocket change to start a new business.” And he had a wild idea. Something that would combine his childhood passion with his knack for branding.

His older sister, Daphne, had seen only the first page of her brother’s business plan. She might have staged an intervention if he had shown her the rest.

His vision was inspired by his father’s week-ends as a shade tree mechanic. Rawlings would simply take that, soup it up, and sell it. “I based everything about the brand on the question ‘what could my dad have done when I was 10 or 15 years old?’… He was barbecuing in the backyard and drinking Coors and cleaning his Mustang. That’s the ideology of Gas Monkey. And that’s kind of what I do on every decision we make.”

Because he needed a business before they could sell a show about business, Rawlings hired Aaron Kaufman, a Fort Worth mechanic who had previously worked on some cars for him, and in 2004 the pair opened Gas Monkey Garage in a tiny 130m2 shop without running water or heat and air. For the next two years, they travelled around the country, sometimes for months at a time, hitting car shows, swap meets, trade events, rallies and anything else they could think of to get the Gas Monkey name out there.

All the while, as he does with the Lamborghini owner in Florida, Rawlings pestered Discovery. He had studied the credits of all the automotive shows on the air, seeing what production companies they used, their management and agencies, and used that to assemble his dream team. He paid to film four sizzle reels showing off his wares. He kept getting close, almost there. This continued for eight years. He compares the experience to the board game Snakes and Ladders: A bunch of new hires would come in at Discovery and he’d have to start all over, again and again. He jokes that they eventually gave him a show just to shut him up.

While he did that, Rawlings needed cash, so he and his wife bought Home Care Providers of Texas — a home-healthcare company, of all things. He needed something more stable bringing money in, and he saw this was a good business he could get his arms around, so he jumped on it.

“I wasn’t giving up,” he says. “I was still making my calls. I still wanted the show. But it was like, Golly. I needed to just get my mind focused and cleared. It turned out to be a good deal because I was able to triple the size of that company in a few months. I was just trying to let my head clear.”

When Fast N’ Loud debuted in 2012, the Gas Monkey team was still squeezed into the tiny shop. But Rawlings knew that wouldn’t last for long. With the pressure of getting the show on the air is gone, everything was about to get bigger – and fast. This was the part he had been waiting for. He had sold Gas Monkey. Now it was time to sell himself.

On the floor of Gas Monkey’s headquarters, there is a thick white line, more than a foot wide, separating the offices from the shop. No matter what is happening, once he crosses that line, Rawlings knows he has to be camera-ready. They film every day. That’s why he had it painted there.

On the floor of Gas Monkey’s headquarters there is a thick white line, more than a foot wide, separating the offices from the shop. No matter what is happening, once he crosses that line, Rawlings knows he has to be camera-ready

Of course, it might be easier for him than most people. He swears there isn’t any difference between how he is on camera and off. When he does speaking appearances, he always asks the first question: “Is the Richard I see on TV going to be the same Richard I see today?” Then he cracks open a beer and tells them, “Damn sure is.”

When the Gas Monkey brand began to take off, Rawlings was ready. He’d already figured out his management style, and he knew how to handle a large workforce in a rapidly expanding business.

“I’m not an authoritarian leader,” he says.

“If I believe in you enough to hire you, and I’ve looked at your credentials, and you say you’re gonna do X, then you’re either gonna do it or not. I don’t need to micromanage you. It’ll be real evident real quick if you can or can’t.”

This is critical because as Gas Monkey grows, Rawlings is forced to delegate more and more. “I just keep pushing things onto plates,” he says. “And there’s a lot of plates out there spinning. It’s the one thing a lot of people don’t get: They hold on too tight.”

Besides, he says, it’s more important to him to be the owner than the boss. In his businesses, Rawlings takes on the same role he has on the show. He has the idea, he makes the deal and then he trusts his team to do the work. That gives him control and keeps his brand from becoming diluted — the fate of many celebrity-driven brands.

“You get an amount of success and celebrity and your door starts getting knocked on Hey, I wanna make cellphone cases with your name on it. Or all these different things. I learned that on the big items — the restaurants, the tequila, the energy drink, the apparel and things like that — most of the time I’m a majority owner. It’s 90 per cent of my money, usually. Other than the large-scale branding and licensing deals, I own those companies and I am backing them. So the authenticity of Gas Monkey and Richard comes through.”

Not every idea clicks, though. He thought he could replicate Gas Monkey Garage with a show called Misfit Garage, which features a couple of his former mechanics and their Fired Up garage. He wanted a competing brand. He wanted to own both Coke and Pepsi. “And it just didn’t work.”

Even when it comes to cars, he can’t flip everything. Rawlings says he’s made as much as $300,000 on a car. But in late 2017, he sold $800,000 worth of cars at a loss of about 30 per cent. He didn’t believe a market would develop for them. “It turned out to be pretty smart,” he says, “because that guy hasn’t been able to sell one of ’em.”

Sometimes he says he can tell before he walks out of the gate that a car that just arrived on a trailer is not the one he needs. He’ll decide then and there to get rid of it. Like he says: Move fast.

Asking Richard Rawlings how many cars he owns is a question whose answer varies depending on the hour. At the moment, he says, there are 40, maybe 50 at his compound. “But I’m in the business,” he says. “They’re all for sale. I only have about four or five I wouldn’t sell. The rest of them are just inventory I get to play with.”

“My goal is not to have the brand I have now,” Rawlings says. “I’d like to have a billion-dollar brand before I’m done. And it’s actually feasibly possible. You can put all the fluff value on stuff – like what is your tequila’s possible worth if you sold it? What is your energy drink? Well, forget all the possibilities. I look at it like: What did we do last year? If you add all the entities, we’re probably a $60, $65 million brand right now – of actual sales, not value. So what are we really worth? And that number gets to be pretty interesting pretty quick.”