Norway’s art scene boomed in the 19th century with the introduction of landscape artists such as Johan Christian Dahl and Johannes Flintoe. Since then, it has seen an increase in local Impressionist, Realist, and Modernist artists, after a long history of importing rather than creating artworks. Today, Norway is proud to have bred many internationally recognised artists, from printmakers to sculptors to jewellers

Norway owes its position in international art history to Edvard Munch, one of the pioneers of modern art. But like most pioneers, Edvard Munch (1863-1944) remained isolated in his own milieu. His contribution had no immediate impact on modern Norwegian art, nor did it attract international attention to Norwegian artists.

After World War II, Norwegian art entered into a steadily more comprehensive alliance with the sociodemocratic programme of social planning. Ideally, art should play a part in public information and be an invitation to an activity which everyone has the right to enjoy.

For many years this view was largely expressed in after-dinner speeches and reports on cultural policy. But the principle had been established. It was beyond dispute, and in this way the foundations were laid for a more consistent official policy towards art as soon as the opportunity arose. And the opportunity came in the 1970s, with their buoyant economy and optimistic view of the future.

Artists formed active, professional organi-sations. The media devoted many columns to their demands to be taken seriously as pro-fessionals with an important social mission. They strengthened their position in evaluating bodies, played an active part in spreading and establishing artistic activity throughout the country and won acceptance for the principle of remuneration for the public display of their works. The result was two-sided, if not more. Norwegian cultural activity became decentralised. Artistic talent was discovered outside the urban concentrations in the capital – not least in local centres such as Bergen and Trondheim. At the same time, Norwegian society became aware that the country as a whole possessed an extrovert and professional pictorial art in keeping with growing national self-esteem.

From an idealistic point of view, Norwegian art was virtually destined to be inventive and to flourish throughout the 70s

Today, however, as the twentieth century draws to a close, the situation has changed completely. This is demonstrated by a notice-able interest in Norwegian contemporary art in international fora, and within Norway itself it is apparent in an equally noticeable optimism and a high level of activity among artists, museum staff, promoters and collectors. This energy is clearly connected with a high level of ambition and quality in the work of Norwegian artists today.

The most obvious explanation is that this is due to the emergence of a particularly large number of good artists – perhaps very good artists. But this alone is not sufficient to explain the present enthusiasm. The answer could be found in a conjunction of circumstances which together form an overall picture of current Norwegian art.

Norwegian appeared as the continuation of the established course among older artists and as exciting discoveries among the very young and those who deliberately looked to the world outside Norway

Thus, from an idealistic point of view, Norwegian art was virtually destined to be inventive and to flourish throughout the ‘70s. But in retrospect, there are many today who wonder whether this public consensus on the objectives of art provided only a spurious freedom and was in fact restrictive in the long term.

With an artist of the calibre of Edvard Munch as part of its heritage, Norwegian art might be expected to have a dominating expressionistic tradition. The fact that this is not so is one of the surprises that abound in the history of art. For although several of Norway’s most important artists have been distinctly expressionist, these have always functioned as outsiders, as isolated single phenomena, not representing any main stream.

But finally, towards the end of the ‘70s, a strongly expressive trend developed in Norway too. The reason to use the word “too” is because this took place parallel to international movements in art, such as “New Expressionism”, “Heftige Malerei”, “Bad Painting” and “Neue Wilden”. In international art the expression of strong emotion and individual selfexpression was in vogue, perhaps as a reaction to the restraint of the technological and conceptual art of the previous decade.

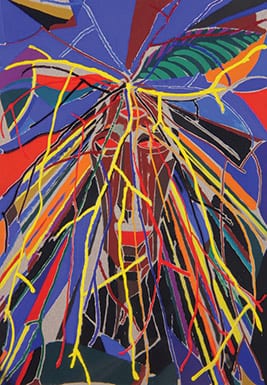

This new, artistic individuality went hand-in-hand with an increasing awareness of the traditional qualities of technique and materials. In painting this meant that the aesthetic effects in the brush strokes and in the refined play of colours again became a focus of interest among the young. Young Norwegian artists were showing more interest in the history of art and a growing sympathy for artistic forms of expression which the older generation had rejected with a shrug. Cubism, surrealism and expressionism were the current art forms, enjoying a popularity they had never known before, not even in the interwar years, when internationally they were the leading art trends. Norwegian art seemed firmly resolved to fill in the gaps in its own recent history.

Norwegian art never made the total break with tradition that international modernism had led to elsewhere. Large sectors of our art have always been devoted to pictorial quality, sculptural modelling and graphic effects, with no apparent concern for problems in the relationship between art and reality. Back came the traditional trends such as landscape painting, psychological, figurative sculpture and graphics based on handicraft techniques. Norwegian appeared as the continuation of the established course among older artists and as exciting discoveries among the very young and those who deliberately looked to the world outside Norway. Continuity became an important factor and in fact began to be identified with special regional characteristics as an art nation. They kept up with international trends, but could also cultivate the national identity so essential to Norwegians.

The new, expressive, individualistic tenden-cies, the awakening interest in older phenomena such as cubism, surrealism and expressionism, and the firmly maintained traditions in techniques and the use of materials all fused together in a variety of surprising combinations in the Norwegian art of the ‘80s. But in this complex picture a number of distictive trends gradually emerged, trends which will no doubt leave their mark on Norwegian art for many years to come.

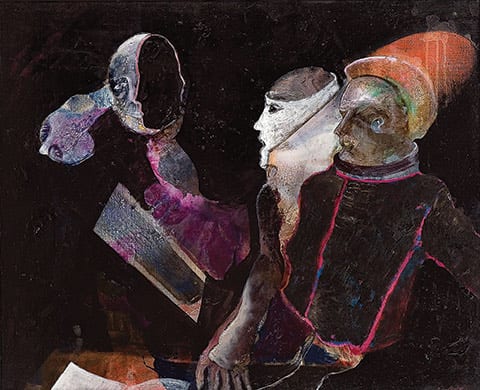

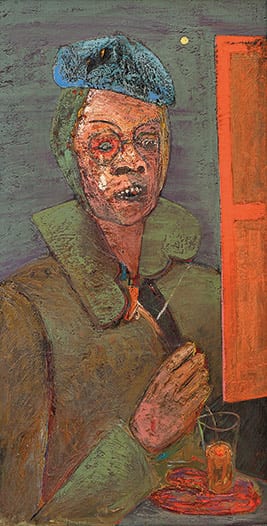

In this context the classical exponent is Bjørn Carlsen (b.1945). He uses very beautiful colours in his paintings, but they portray disquieting visions in which birth and death, violence and tenderness all melt together into a whole. A sort of sublime, harmonious universe revolves around mankind, which is portrayed without illusions, but also without disgust.

Another leading exponent of this disturbing use of the fantastic is Knut Rose (b.1936). His pictures too have an alluring beauty, but the rich, glazed layers of colour reveal threatening glimpses of a hazy dream world, where man appears lost in aimless games, with no meaning and no goal.

There are of course exceptions to generaliza-tions of this sort. An artist of the importance of Bjørn Ransve (b.1944), creates to all appearances unusually sophisticated paintings in constantly changing styles, which are all part of the debate on the relationship between art and reality.

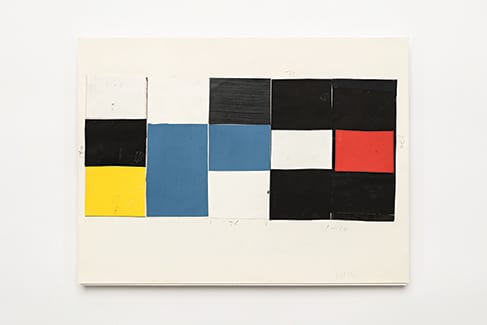

The most important exponent of neo- for-malism, where the content plays no decisive role is Arne Malmedal (b.1937), in fact projects an understated view of the picture, based on great pictorial experience and wide knowledge.

But, no one has gone as far in allowing the surface of the picture to dominate its expres-sion as Bjørn Sigurd Tufta (b.1956). His dark, textured pictures are, in their strict abstraction, a kind of emblem.

In this complex picture a number of distictive trends gradually emerged, trends which will no doubt leave their mark on Norwegian art for many years to come

Alongside pure virtuoso graphics, it could be find all kinds of transitional forms between graphics and drawing, painting, sculpture and installations. An artist such as Yngve Zakarias (b.1957) has made prints which are material pictures, and diary leaves which have almost the same form as wall grafitti.

The fact that drawing is also part of this dynamic field is something totally surprising in Norwegian art. A pioneer in this field is Zdenka Rusova (b.1939) who, in her large compositions, gives us the feeling of dramatic growth processes.