His name is mentioned with great respect. Milena Dravić and Dragan Nikolić remain unsurpassed as a couple in his series Cheek to Cheek, Zoran Radmilović was at his best when acting in his series More Than a Game. His film Zona Zamfirova was watched by 1.2 million people, which is an unparalleled record in Serbia.

Now we are awaiting his series Santa Maria Della Salute, depicting the life of great Serbian poet Laza Kostić and his love for the young Lenka Dunđerski. And to all of this, he says All my life I have loved only that which I do. And I barely understand a little about that!

It is enough that he made the series More than a Game and Cheek to Cheek. But his signature is also attached to dozens of television dramas that have been trademarks of Television Belgrade over the past five decades. He has also directed around 20 films, achieving the absolute record for viewership with Zona Zamfirova, which recorded a total of 1.2 million viewers.

The public also swarmed to watch Ivkova Slava and his second film, after Zona, made based on a work by Stevan Sremac. He earned the most prizes and awards at international festivals with his films Idemo dalje, Držanje za vazduh and Braća po materi. He resurrected the forgotten Mir Jam, whose Wounded Eagle as a TV series adaptation showed how the Serbs discovered and fell in love with melodrama. He didn’t relax until he had made a screen adaptation of Milovan Vitezović’s Šešir profesora Vujića, in which Aleksandar Berček played one of his most significant roles.

He delighted audiences once again at the end of last year with the feature film and television series entitled Santa Maria Della Salute, which has been broadcast on RTS since March this year. As he explained, this television-film endeavour aims to affirm the highest national, cultural and social values.

The series brings to life an exciting picture and history of Vojvodina and Serbia during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, as well as the tragic platonic love between poet Laza Kostić and the young Lenka Dunđerski:

“The story of Laza Kostić contains important elements that comprise our national identity and cultural history, from which we should learn. The very appearance of poetry refines the viewers during this time when values have been lost. The area is lagging, and we must push it up from the bottom – notes this famous director, adding that this is his career’s “most complex and most demanding project”.

Zdravko Šotra was born as the seventh child of Mara and Đorđe Šotra in the village of Kozica, in the area called Dubrava, which forms a triangle between Stolac, Čapljina and Mostar. This Herzegovina native grew up in Kosovo, where his family moved on the eve of the outbreak of World War II

Šotra spent three years investigating the details of the poet’s life, after which he wrote a screenplay that will show viewers that Laza Kostic was a versatile personality in many ways, who wrote poetry, dealt with politics, slaved to defend the interests of his people, but who was above all a great poet.

He became an MP but soon realised that he was not a politician in his soul, rather that he was doing this work out of a desire to help his people. And if he’d only written the poem Santa Maria Della Salute he would have been a great poet, because it ranks high in the poetry world.

The Gallery of Historical Figures from the cultural, political and public life of Serbia, Montenegro and Vojvodina will contribute to the credibility of this exciting story, whose main characters, Laza Kostić and Lenka Dunđerski, are interpreted by Vojin Ćetković and the young Tamara Aleksić. Ćetković reveals that his favourite Kostić poems are Santa Maria Della Salute and Between wakefulness and the dream, as the two most beautiful poems written in our language. Tamara Aleksić also has great respect for Laza Kostić and his poetry.

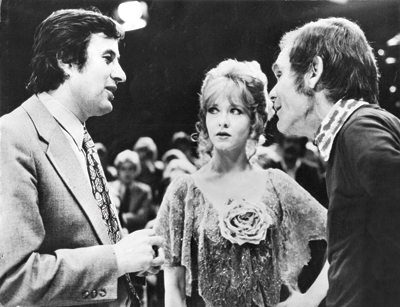

Colleagues and film artists speak the name of Zdravko Šotra with great respect. Young actors aspire to perform under Šotra during their careers. Some greats, such as actor Zoran Radmilović, made their most significant television achievements precisely with Šotra – Slobodan Stojanović’s series More than a game is considered Radmilović’s best success in front of the TV cameras. The last major role of Dragan Nikolić was a touching interpretation of Chekhov’s character Uglješa Knežević in Šotra’s series Wounded Eagle, while forty years earlier Milena Dravić and Dragan Nikolić formed a unique couple in Šotra’s Cheek to Cheek, which remains a modern template for a successful show on Serbian television to this day.

A few years ago, Šotra (83) summarised his life in the biographical work Hanging on for air (published by Vukotić Media), in which readers discover how this boy from Herzegovina survived World War II in Kosovo, and what it was like for him to be left on his own at the age of 12, being more hungry than full? What was recorded about the greatest Serbian actors, Milivoje Živanović, Mija Aleksić, Pavle Vuisić, and most of all Zoran Radmilović, by the director who loved them? What forms the greatness of Bata Živojinović, Dragana Nikolića and Milena Dravić, and how the entry into his life of Professor Dr Neda Todorović also marked the end of years of loneliness? Šotra has a son Marko, a director, and grandchildren Luka (18) and Petar (2).

The Šotra family are from the part of Herzegovina where the Serbian population was killed in the last three wars. They have been left in pits, while those who survived mostly abandoned their native region as refugees. Today they are in Herzegovina the least. A close relative of Zdravko, namely his first cousin on his father’s side, is Branko Šotra, an exceptional graphic artist who founded the Academy of Applied Arts in Belgrade after World War II and served as its dean and professor.

Due to my genetic and artistic impulses, I was preoccupied by the thought of making a film about Jovan Dučić. This is a love story through which his life and extraordinary personal and artistic biography refract. And he was handsome, talented, renowned, wealthy…

Zdravko Šotra was born as the seventh child of Mara and Đorđe Šotra in the village of Kozica, in the area called Dubrava, which forms a triangle between Stolac, Čapljina and Mostar. This Herzegovina native grew up in Kosovo, where his family moved on the eve of the outbreak of World War II:

“By sheer coincidence, my father came to Kosovo in 1938, and we survived there. But ending up in the pits were my 82-year-old grandmother, who gave birth to 13 children, and my aunts and uncles … 38 of them from the Šotra family. As a child, I was not fully aware of that horror. Many years later, just before the wars of the ‘90s, the government finally allowed those cemented pits to be opened and for the bones to be buried according to human customs. One of my colleagues received an order to film that, but I begged him to let me go instead. So I spent days and nights filming the opening of the six Stolac pits from which the bones were extracted. I found that truly distressing. Then several years passed, the war started, and the crypt that was made as a collective tomb for the slain Serbs was blown up.”

Asked what is left of his Herzegovinian origins, he answers:

“Everything. I’ve been living in Belgrade for so long, but I haven’t managed to change anything of that mentality I brought from Herzegovina. And for my whole life, I felt better as soon as I went there. Now it is almost impossible to go to the area of my birthplace, but I often went to Trebinje, the most beautiful place where Serbs live. I began going there intensively when I made a film about the transfer of the bones of Jovan Dučić and followed the construction of the church in which he was buried. My countrymen often asked when I will make a film from my area. Not only for this reason, but also due to my genetic and artistic impulses, I was preoccupied with the thought of making a film about Jovan Dučić. This is a love story through which his life and extraordinary personal and artistic biography refract. And he was handsome, talented, renowned, wealthy … He lived in the most beautiful places in Europe, was educated in Geneva and Paris, was celebrated for his brilliant poetry and was also a diplomat and a beloved man. The whole topic is very delicate, but primarily challenging. However, now viewers can see the no less interesting and challenging story of another giant of poetry, Laza Kostić.”

Šotra has tried to avoid politics all his life, but it has scratched at him in many ways. A story remains that he made the film The Battle of Kosovo during the period of Slobodan Milošević’s rule to mark the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo in a dignified way, but also because that was what the then president of Serbia wanted?

“I’ve also heard that nonsense. Slobodan Milošević had no idea what I, in my thoughtlessness, had embarked upon. Some Italian journalist came to talk to me because he had clearly been instructed that I was one of the creators of the Greater Serbia project and the celebration of St. Vitus Day in 1989. I explained to him that the Battle of Kosovo was the defeat of the Serbian people, after, which began centuries of Serbian slavery. And there is no reason for any glorification of that battle and that disaster. Otherwise, the truth was that the then director of TV Belgrade, Nenad Ristić, asked me to film one great poem by Ljubomir Simović, entitled The Battle of Kosovo, with actors sitting in a studio in tuxedos reading the text. And I wanted to improvise with that a little, in short, to create a historical spectacle on this basis which I had a month to do. It was only when I started working that I saw the kind of nonsense I had gotten into and I had to force it to the end. Milošević did not appear at the premiere. Still, the man then presiding over Yugoslavia, Slovene Janez Drnovšek was there, as were members of the diplomatic corps and various other invitees, and I after the premiere I collapsed and ended up in the emergency room.”

“Otherwise, I was in Kosovo for the first time on St. Vitus Day 1939, when I was six years old. My father rented a car and drove us to Gazimestan, where they were celebrating the 550th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo. We went to the funeral service in Gračanica, where I first saw the Nemanjićs on the walls. If I were someone, I would now say that back then, as a six-year-old boy, standing there before the Nemanjićs, I promised myself that over the next fifty years, to mark the occasion of 600 years since the Battle of Kosovo, I would make a film.”

This hardened Red Star supporter has long since ceased to attend the matches. Just as football is at a low ebb, so he says that many values in society have been greatly degraded: “There’s nowhere left to fall”

Few people know that the series More than a game, one of the best projects of its kind ever implemented on domestic television, waited two years to be approved for screening because Šotra had filmed it based on a screenplay written by his dear and the early departed friend, writer Slobodan Stojanović. Was it because of that that he was in a bunker during the 1970s?

“The answer to that question is better known by those who prevented the broadcasting of that series. I know that they were approaching some Tito jubilee, do not ask me which, because they were always happening, and they did not dare, on the eve of a great jubilee, to allow the emitting of a series that addressed the pre-war bourgeois world in Serbia, which gained a large area during World War II. This, until that time, was not normal. How could a single officer of the Serbian Army be more prominent than the party secretary? We finished the series in 1975, and it was aired in 1977. I don’t believe that someone prohibited the series from the outside. That was done by people from the company who feared for their position.”

Asked what party comrades criticised about that series, Šotra today recalls:

“There were 36 specifically listed things that had to be removed or changed. I accepted three or four. For example, I removed a scene in which a German soldier enters a pharmacy and whispers something to the pharmacist. The pharmacist responded to this by saying: Sorry, we only have our sizes, and they will be big for you! If we assume that the German soldier wanted to buy condoms, I removed from the series the glorification of something Serbian, which was big. It was not good to glorify anything Serbian, even if, as in this unproven case, that was the Serbian member! And so I did not want to give up, and they did not give in, until the appearance of a reasonable man, named Filip Fića Matić, who saw the series and said from the position of President of the Belgrade TV Council – Broadcast it, immediately!”

At one point, Šotra received support from Ivan Stambolić and was briefly a member of the Municipal Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in Belgrade:

“That was the time when we Sloba Stojanović and I, as members of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, launched the slogan: I ask the Party to release me from its ranks. Someone pushed me into that combination at that moment. Ivan Stambolić was then president of the General Committee of the League of Communists of Belgrade, and he wanted to change the composition of the Committee a little, so I probably found myself in that package. However, I went out, said something that did not fit in any way with expected party activities, and they played dumb as if they had not heard. They didn’t get any fortune from me.”

Other parties also didn’t have any luck with this director:

“Other parties weren’t very interested in me. They only called if they needed something. They mostly left me alone, which also suited me fine.”

I’ve been living in Belgrade for so long, but I haven’t managed to change anything of that mentality I brought from Herzegovina… Now it is almost impossible for me to go to the area of my birthplace, but I often went to Trebinje, the most beautiful place where Serbs live

One year, before the breakup of Yugoslavia, Šotra had an interesting dialogue at the film festival in Pula with Azem Vlasi, a then politician from Kosovo who wanted to explain to this director why his film The Conquest of Freedom was no good:

“That was my first film, made based on a screenplay by Gordan Mihić, and it was accepted into the official selection of the festival. The reasons were of a political, ideological nature, and the fact that it was not included in the official programme because of this provided reason enough to cause more of a hullabaloo over this film than its quality deserved. The film was not worth as much as the praise it received. Otherwise, that Pula festival, like many others, appeared tragicomic when it comes to the jury’s decisions. Delegated as jury members were members of the republican central party committees, who were tasked with packaging the award for films from those republics because then the producer of the award-winning movie would receive money from the SIZ for culture.

Thus, one of the jury members that year was Azem Vlasi, from Kosovo. There were a total of 13 jury members, including two or three directors and the odd actor, who crucially could not influence anything. For there to be as little competition as possible for awards, they removed films that would bother them unnecessarily. Thus I was removed from the game at the start because it was best to stick a label of politically unsuitable to the film. I saw in the later report that Vlasi was at the forefront of that. And then it happened that he approached me at the bar. We otherwise did not know each other, but he pointed his index finger at my face and said: I will explain to you what’s wrong with your film! I retorted: You understand a movie like Marica understands a bent dick! Vlasi turned red, turned around and left.”

From the great Milivoje Živanović, via Zoran Radmilović, Dragan Nikolić and Aleksandar Berček to Nikola Đuričko, Vojin Ćetković and Ivan Bosiljčić… there is almost no actor who has not performed in some of his dramas, TV serials or films. And this is why we should believe him when he says that great actors are, as a rule, easy to cooperate with:

“The bigger they are, the easier they are; the weaker, the tougher. They often know how to say to me: “it’s easy for you when you work with good actors”. Well, which other should I work with?! Some directors shy away from acting greatness, worried that they will not be able to tame them. I did not even shy aware from the greats when I was young. I did two dramas with Milivoje Živanović. He would be the first come to rehearsals, the first to learn the text. And standing next to him would be an acting student who would do everything the opposite of him; who would arrive last and would be the last to learn the text. So I also worked with Pavle Vujisić, Zoran Radmilović, Slobodan Aligrudić and Slobodan Cica Perović. The latter found it very difficult to learn the text, but he was capable of overcoming that with many surprises in his acting creativity. All of them generally drank a lot, but that could never be felt and was not reflected on the job.”

This hardened Red Star supporter has long since ceased to attend the matches. Just as football is at a low ebb, so he says that many values in society have been greatly degraded:

“There’s nowhere left to fall. That situation in which we lived and are still living was described ingeniously by a Romanian poet when they brought down their president Ceausescu. He more or less said: “We headed to one side, went astray, and saw that nothing exists there. Now we are coming back, and we can explain to everyone well no to head to that side because there’s nothing there. You could pay us something for that report, as we brought you very important information.”

“And now I think we could also sell that kind of information; that great discovery of ours that there is nothing in that place where we have been in recent years.”

And when a reporter thinks that we could now continue talking about politics, Šotra replies ironically, in that Herzegovinian way, but primarily in accordance with himself:

“I don’t understand anything in politics. All my life, I have loved only that which I do. And I barely understand a little about that.”

As in every life, Šotra concludes that he has included all sorts of things:

“In my twelfth year, I ventured out into the world and life without any real view of survival. There were countless chances for me to fail, but given that I survived nevertheless, made something of myself and forced my way to these years, I have to be satisfied. There have been worse cases.”