He was four years old when jazz started being playing in Serbia. Today has reached the ripe old age of 93! He founded the first jazz orchestra in Serbia and was its conductor for 30 years, and has also met and heard the world’s greatest jazz musicians. He claims that jazz was viewed in post-WWII Yugoslavia with great suspicion; that the communist authorities didn’t like jazz, but he didn’t like the communists, so they were all square

On the territory of the former Yugoslavia, there is no older jazz musician than him. Vojislav Bubiša Simić (93) is incredibly vivacious – a fact he convinced visitors to the Belgrade Jazz Festival in the Belgrade Youth Centre this autumn. On an evening dedicated to late jazz musician and great saxophonist Milivoje Mića Marković, Bubiša spoke unscripted for fifteen minutes about his junior colleague by 15 years, speaking with unmistakable precision when manifesting his fascinating memory. And for this interview, he also effortlessly recalled what the times were like seven and eight decades ago.

Bubiša is a child from a good home, as it used to be said, and is now said for someone who’s the son of a distinguished lawyer, and was raised in his grandmother’s house at 39 Majka Jevrosima Street in downtown Belgrade. He graduated from the famous Second Boys Gymnasium (High School), whose teachers were among the academics of the time, and whose pupils became academics, Belgrade University professors Milan Bartoš, Bogdan Bogdanović, Pavle Savić et al.

He graduated from the Music Academy, while his love for music defined his future life from early childhood: “My mother, like all the good city girls of that time, knew French well and played the piano. I was 12 years old when I began to play the keys. She saw that I had talent and took me a piano teacher, and after a year I could play Chopin’s easier waltzes. When I graduated from primary education or turned 14, my grandmother bought me a piano that was placed in the salon on the first floor and I practised there.

He graduated from the Music Academy, while his love for music defined his future life from early childhood: “My mother, like all the good city girls of that time, knew French well and played the piano. I was 12 years old when I began to play the keys. She saw that I had talent and took me a piano teacher, and after a year I could play Chopin’s easier waltzes. When I graduated from primary education or turned 14, my grandmother bought me a piano that was placed in the salon on the first floor and I practised there.

On 6th April 1941, German planes started bombing Belgrade and my family fled to Ripanj, a village near Belgrade, where my father, a reserve officer, had been stationed. We returned to Belgrade after five or six days and found our house half-demolished. Below the ruins we saw my piano, we barely dug it out and everything wooden on it was broken, but it produced sound. After a month of work, the piano master recomposed it, I started practising on it again, and after the war, I enrolled in the Music Academy, continued practising on it and prepared for my graduation exam.

I graduated in conducting, aware that I would never become a pianist, and sold the old piano. Sometime in the late 1970s I visited the Music School in Zemun and saw the old piano that I’d sold. I was very excited, so I sat down and began playing. However, I started to recall memories from that time when my grandmother bought it, so I got up and left the room, so my colleagues wouldn’t see me crying. That’s how my old piano and I broke up, and I never saw it again.”

Have you noticed that some scenes of post-war domestic films were very similar? For example, whenever a German appears, a domestic traitor or a prostitute, it is usually in a bar where jazz is playing. This music was most suited to our directors when they wanted to show enemies, or negative characters

When he was 15 years old in 1939, Bubiša’s father bought him for his birthday two records of Count Basie, in the music store at 23 Terazija. The records contained Basie’s great hits, and this was Bubiša’s first encounter with this jazz great. All Bubiša’s records were destroyed, snapped in half, during the bombing of the house they lived in, and Bubiša was very sad about that. When he participated in the jazz festival in Juan Les- Pins in France in 1960, Bubiša wrote the composition Greetings to Count Basie, and with it, his orchestra won at the festival. Five years later he met Count Basie in Munich and handed him the composition dedicated to him:

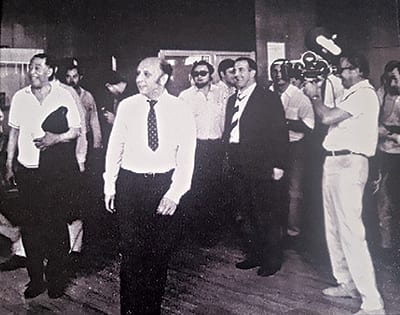

“He promised to perform it as soon as he could… In 1975 I was director of the Belgrade Spring festival, and in this capacity, I was the host of Count Basie when he held a concert in Union House. During my stay in the U.S. in 1982, Basie had a concert with Sammy Davis junior at Cesar’s Palace. I went to the concert, enjoyed it, and then wanted to see him after the concert. They did not want to let me through, but his son was there and I explained to him that we knew each other and that I was his great admirer. He let me through, and to my great sadness, I saw an old man in a wheelchair with a slightly little lazy eye that wandered. I asked him to give me an autograph and he barely signed a picture with his trembling hand. It was unbelievable: on stage, in front of the piano, it was that Basie of 1938, because jazz brings him back to life. Only jazz kept him alive. He died a year later.”

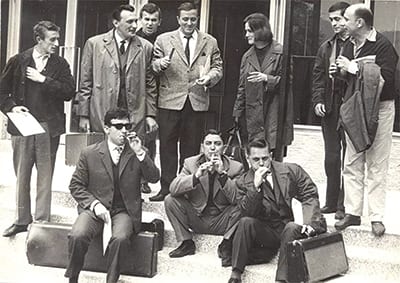

After World War II, in 1946, Bubiša founded the amateur jazz orchestra ‘Dinamo’, the first big band in Serbia. From 1953 to 1985 he was the conductor of Jazz Orchestra of Radio Television Belgrade, with which he travelled throughout almost the whole of Europe and achieved great successes. The most significant was the first prize at the aforementioned Jazz Festival in Juan-les-Pins in France in 1960. In his books, he has described events from the time when jazz was on the margins of the music scene in Serbia, and in response to the question of how that time from the beginnings of jazz in Serbia looks today, whether that was the conquest of freedom or a boyish game, he tells CorD:

“It may sound pretentious, or even pathetic if I say that it was conquering freedom. But it was rather than us playing. When we founded the jazz orchestra in 1946, nobody thought about banning it, but, as my grandmother said, they gave us dirty looks. We were viewed like every novelty, which jazz undeniably was in those post-war years, which meant that we all were restrained and suspicious. As a rule, we were very educated as musicians, because you couldn’t play jazz if you did not have a musical and general education. We all came from urban families where one graduated to having a good upbringing, a good general education, and no fear of the great world. Alongside that, there were no communists among us, because communism and jazz didn’t go hand in hand. Otherwise, very, very rarely you could find among jazzers someone who was not from the urban class that – clearly – was not valued in the period after World War II. Jazz was not seen as a profession, but rather a hobby. I loved jazz like a first love that I never left.”

Regardless of the authorities who didn’t look favourably on the jazzers who persisted with their choice, it could be said that this was still a time of freedom for this music in the then Yugoslavia, because the situation was much worse in all other socialist countries, especially in the Soviet Union. Testifying about that today, Bubiša says:

For Bubiša, the alpha and omega of jazz was Duke Ellington, the American pianist, conductor, composer and arranger, who he first heard at the jazz festival in Prague in 1969. This musician came to Belgrade with his orchestra the following year

“Interestingly, prior to World War II, jazz was very developed in some of those countries, like Czechoslovakia, for example, but after the war, it was all suppressed. American songs and American vocals were avoided, as it was considered a bad influence on the youth who loved to listen to it. Also, here it was thought that jazz was not artistic music at all, that musicians did not know notes, but we all knew the notes and plus we knew almost all the compositions we performed by heart.

Nevertheless, the struggle for jazz was current for all the years after the war and we didn’t relent. It can’t be said that anyone persecuted or arrested us, because the then communist regime was threatened much more by writers, dramatists and even painters. Have you noticed that some scenes of post-war domestic films were very similar? For example, whenever a German appears, a domestic traitor or a prostitute, it is usually in a bar where jazz is playing. This music was most suited to our directors when they wanted to show enemies or negative characters”.

In 1956 Belgrade hosted the orchestra of Dizzy Gillespie, which had two concerts, one at Kolarac and the other in the hall of Garda House in Topčider. Quincy Jones was playing the trumpet in the line, like some accidental. This was Bubiša’s first live encounter with the jazz greats. He had a place on the balcony of Kolarac and he leaned so far over the balcony to see every musician that he almost fell over. A few years later came the Oscar Peterson Trio, Ella Fitzgerald and others.

The first time that the Radio Jazz orchestra of Radio Belgrade launched an international tour was in early March 1957. It was a three-week tour around the then East Germany. That same year they also toured Hungary, and Bubiša used the money they earned there to buy an East German magnetic cassette player that was so heavy he could hardly carry it off the train. In the winter of 1958 they had a tour of Poland, then returned to Hungary… and on 25th May 1959, Bubiša met Josip Broz Tito. He conducted a festive concert for Tito’s birthday at the Belgrade Fair, and after the concert, they were told to come to the reception that Tito was organising. When he approached him to wish him a happy birthday, Bubiša, who was otherwise an anti-communist, like his father, asked Tito: “Is it true you don’t like jazz?” To which Tito immediately replied: “No, it’s not true. I love it, especially the original type. See, I was just in Sudan and had the opportunity to listen to it. However, the Americans commercialised jazz”.

The newspapers that then existed carried Tito’s sentence, Bubiša gained great fame in Radio Belgrade, and after that, the attitude of Radio Belgrade’s leadership towards the members of the jazz orchestra relaxed slightly, and they could play more freely and have a greater choice when it came to the compositions performed. Tito, however, never again mentioned the word jazz publicly:

“When Tito began to pursue a policy of opening up towards the West, Yugoslavia had to open up. American films arrived, American music and jazz began spouting like a tsunami. Its enormous ascent was followed here by the great interest of the public, and that all lasted until the appearance of the Beatles. They appeared like something completely new, but they also performed good music that flooded the Planet.”

This conductor and composer don’t think jazz began losing the competition with rock and that the rock was an enemy of jazz. In his opinion, the greatest enemy of jazz was newly-composed folk music:

“That newly-composed folk music was the only one to cause jazz to suffer in our country. That’s also so today. This music took elements of fun music (rhythm), instruments (electric guitar, electric bass, synthesizer), even saxophones and trumpets, and gained immense popularity. However, real jazz musicians and they exist all over the world and here, regardless of the money, don’t want to play anything but jazz.”

The fact that this music was underrated by the authorities after World War II is no surprise, but Bubiša was surprised that neither musicologists nor music critics wrote about jazz as a musical form and direction that had many fans and followers in Serbia

For Bubiša, the alpha and omega of jazz was Duke Ellington, the American pianist, conductor, composer and arranger, who he first heard at the jazz festival in Prague in 1969. This musician came to Belgrade with his orchestra the following year, and Bubiša prepared a huge surprise for him: with the orchestra of Radio Television Belgrade, he practised from memory Take the A Train, the Duke’s trademark track. The entire orchestra went to the airport, set themselves up in the hall, and Bubiša awaited Duke as he disembarked from the plane. And when they entered the hall, the music thundered. Duke and the members of his orchestra were stunned in wonder; Duke approached and began conducting. When the famous composition had been performed, Duke approached each member of the RTB Orchestra and greeted them: “Ellington’s music is the very core of jazz.

I think that was the best jazz concert the Belgrade audience ever heard in its own city. In the break between the two concerts, in the improvised cloakroom, we prepared various specialities from the restaurant Kasina, but he just asked for strong beef soup, because that gave him strength. When I saw him off at the airport, he thanked me for my attention, gave me a program of concerts with an address which read: To Airport Orchestra – Buona Fortuna. I could only laugh at it. He forgot everything that I told him about who we were and what success we had as a national jazz orchestra. He remained in the belief that we were an airport orchestra! Two years later, in 1972, at the Edison Hotel where I spent my stay at the Newport Jazz Festival, I met the members of his orchestra who remembered who I was after the welcome at the airport. They were passing through New York because they played in Cotton Club in Harlem that night where Duke began his career. I asked them to take me to hear them, but they told me they didn’t dare because they feared for my safety as a white man. They told me that I could only be safe in Harlem if I was personally brought there by Mr Ellington. I didn’t manage to find Duke, so I didn’t go to the Cotton Club. And today I’m sorry about that.”

When reconstructing his memory and recalling his knowledge of the history of jazz, CorD’s interlocutor concludes that jazz came to Serbia in 1928. And has been consistently present since then, with lesser or greater successes. The fact that this music was underrated by the authorities after World War II is no surprise, but Bubiša was surprised that neither musicologists nor music critics wrote about jazz as a musical form and direction that had many fans and followers in Serbia:

“That ignoring of jazz lasted for many years. It was always somehow on the margins, but with jazz, it is a big problem that it has its permanent followers and that musicians who choose jazz don’t give it up easily. There was always the story that these musicians were either drunks or on drugs. Of course, there was also that. There are well-known stories about how famous singer Billie Holiday used opiates, as well as many other jazz musicians, but they were primarily great musicians. I know many who couldn’t play without alcohol, but they were brilliant musicians nonetheless. Of course, I’m saying all of this about jazzers who I knew, listened to, loved. Drugs later took the lives of some musicians, like today. However, jazz musicians are on the same level as other musicians and have to take care of whether they are in shape, how they live, how much they sleep…”

“The world I belonged to as a musician was a world devoid of vanity, or to say that among jazzers was the least vanity. We recognised each other wherever we met and acknowledged each other for what we were able to do…”

Bubiša never smoked and didn’t even drink unless he needed to make a toast, but didn’t avoid the taverns and liked to travel, visiting jazz clubs around the world, and today he’s sorry to see that there are much fewer than decades ago, especially in America – the land where jazz was born. For him, jazz is a constant gig and a constant tour, which is nowadays an ever-rarer phenomenon:

“I was lucky to be dealing with jazz in the years when the orchestra I conducted for 30 years spent most of its time on tour. And there was no greater satisfaction than getting a new crowd joining jazz from city to city, meeting colleagues, musicians, various celebrities. I never feared the authorities or liked them, whatever government it was. My world was records, instruments, good music and good musicians. The world I belonged to as a musician was a world devoid of vanity, or to say that among jazzers was the least vanity. We recognised each other wherever we met and acknowledged each other for what we were able to do.”

It should also be mentioned in this story, however, that Bubiša spent his whole life surrounded by his family, which gave him peace and stability. Even today, as we speak, his caring wife Edit is beside him, his two daughters and grandkids live their own lives. After several books he has written about his life and work, he is finalising a new one. He says that he still wanted to record some of the histories of jazz that should remain recorded. No other musicians in Serbia have had such a rich life, and even fewer of them have endured as long as Vojislav Bubiša Simić.